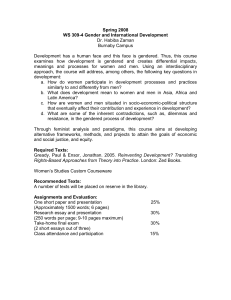

HIST G8500 US Historiography Professor Mae Ngai Fall 2011

advertisement

HIST G8500 US Historiography Fall 2011 Professor Mae Ngai Manuel A. Bautista González Policy Alice Kessler-Harris traces the quest of American women to obtain economic citizenship, the “independent status that provides the possibility of full participation in the polity” from the 1930s to the early 1970s1. Kessler-Harris understands gender as a “continual and changing process”, as well as “a system of thought and a category of analysis” 2. Her story unveils the embedded values and habits of mind on women (the gendered imagination) hidden in state actions and social policies, which in turn restricted women’s access to economic citizenship. Her sources are mainly official records from the “legislative, judicial and policy-making apparatus” 3. Kessler-Harris’s book can also be read as a historical explanation of gender-based inequality. Labor economists have assessed the difference in male and female wages but rarely have they historicized their explanations4. Kessler-Harris shows unexpected channels through which policy measures create incentive mechanisms that perpetuate the state of things. It is fair to say that her book explores the scope and limits of the gendered imagination and its economic and legal performativity in 20th century America. The gender approach to economic citizenship advocated by Kessler-Harris can certainly inform not only political and labor histories but other disciplines as well. Valuable insights are to be found in this book for scholars of management, fiscal history and the history of economic, such as with the experiments and studies on the work of women in different American corporations (Chapter 1), and the direct taxation policies of the New Deal era (Chapter 4), as well as the frequent references throughout the book to economists engaging in public debates regarding women’s labor. The hiring (and firing) practices of corporations such as General Electric, Ford and the experiments in the Western Electric Company not only are cases of gender discrimination and scientific approaches of the Progressive era to productivity differences between the sexes: they can also inform legions of businessmen and management scholars to shape better guidelines for human resources policies based on historical evidence5. In her revision of the taxation policies of the 1930s and 1940s, Kessler-Harris ably produces a gendered view of aspects that might escape to fiscal historians studying income tax policies in America and elsewhere: the efforts of fiscal officers to jointly tax married 1 Alice Kessler-Harris, In Pursuit of Equity. Women, Men, and the Quest for Economic Citizenship in 20th Century America. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005): 5. 2 Kessler-Harris, In Pursuit of Equity: 6. 3 Kessler-Harris, In Pursuit of Equity: 295. 4 The classical work from an economic history approach is Claudia Goldin. Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990). 5 Kessler-Harris, In Pursuit of Equity: 45-56. couples and the resistance Treasury found in Congress and the public add to unexplored aspects of fiscal policymaking6. The epilogue of the book is worth mentioning as a valuable example of the relevance that the personal experiences of a historian are in her framing of a problem and her writing of a tale. Kessler-Harris’s own involvement as a rebuttal witness in a judicial case on gender-based discrimination against Sears illustrated the resistances to change that she explored throughout her book7. Kessler-Harris offers a compelling demonstration of how relevant historical readings are when guided by concepts such as gender, class, ethnicity and race. To my understanding, the most important lesson we can obtain from her book is that seemingly neutral laws and policy measures are never addressed to the individual in abstract, but are biased by ideas and prejudices common to any society in a period of time and might in fact reproduce (and amplify) their effects in daily life. Kessler-Harris’s approach to an economic and political problem made me question my own assumptions and preconceived ideas on gender inequality. It also made me think about the pertinence of applying historical methods of inquiry to scholarly literature: academic texts are also embedded with habits of mind, the biases and prejudices of their authors, and thus historians must be prepared to have a critical gaze and expose whenever possible the impact of the “gendered imagination” and other imageries in existing scholarship. 6 7 Kessler-Harris, In Pursuit of Equity: 177-202. Kessler-Harris, In Pursuit of Equity: 290-292.