2.1 identification collection selection lecture note

advertisement

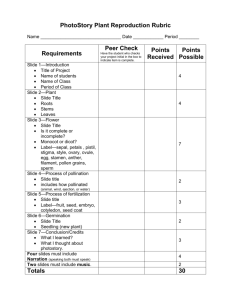

Session 2.1. Methods for identification, germplasm collection and selection Training Workshop on Allanblackia Domestication, 23 to 27 Oct 2006 Ian Dawson c/o The World Agroforestry Centre, Nairobi, Kenya Learning objectives Participants will be able to: Relate the importance of germplasm identification, collection and selection to the Allanblackia agri-business. Explain the key issues that need to be considered during identification, collection and selection. Relate the actual approaches used for Allanblackia collection and selection to date. Explain ‘best practice’ for practical deployment and key constraints/gaps in understanding that require further attention. Instructional methods 45 min classroom presentation (PowerPoint) with open discussion. Instructional materials ‘Lecture’ note, copy of PowerPoint presentation and references. Summary The Allanblackia agri-business requires than several million trees be planted across countries participating in the initiative each year from 2008 onwards. Germplasm of the right species must be provided in a suitable form, in sufficient quantities, and in a timely manner for farmer planting. At the same time, supplied planting material should be capable of consistently producing good quantities of high quality food oil. Identification of the right Allanblackia species for planting is important in order to properly address quality and performance issues, and may be important to prevent outbreeding depression and properly facilitate circa situ conservation. Identification of different Allanblackia species is relatively straightforward, with few problems anticipated, even in cases where species distributions are sympatric (overlap) in Cameroon and Tanzania. Germplasm collection of Allanblackia has been undertaken for a number of reasons, including for raising planting material for distribution to farmers, for tree management research, for genetic improvement programmes and for ex situ conservation. Collections have used a number of approaches, with material sampled as seed and vegetatively, and using random and targeted methods. A brief description of the theory behind the different approaches that have been applied, each of which has potential advantages and disadvantages, is given here. Vegetative sampling carries a number of advantages compared to seed collection in relation to selection, gender determination, and the physiology of collected material (earlier fruiting?), but requires more resources, both during and after collection, to undertake properly. Whilst targeted collection appears an attractive approach, it also takes more resources than random sampling to do properly, and re-collection (on return to a site) can be more difficult. Following this analysis a description of key issues important to all collections, irrespective of the approach used, is given. Selection of Allanblackia for seed yield is underway during some collections, based on observations on fruit size during surveys of natural stands. General issues related to selection are here considered, including a consideration of the value of applying selection during seed and vegetative sampling. Whilst selection from natural stands appears an attractive proposition, there are reasons why it may not be as effective as collectors may assume, especially if germplasm is sampled as seed. Summaries of current best practices for collection and selection, and key gaps in understanding that in the future need to be addressed, are given. For collection, determination of the efficiency of different approaches to sampling is a key issue. For selection, wider consideration of the suitable characteristics by which ‘superior’ material is defined (e.g. stability of production) is very important. Key references Dawson I, Were J (1997) Collecting germplasm from trees. Agroforestry Today, 9 (2), 6-9. Lecture note The Allanblackia agri-business requires than several million trees be planted across countries participating in the initiative each year from 2008 onwards, for a number of years. Germplasm of the correct species must be provided in a suitable form, in sufficient quantities, and in a timely manner for farmer planting. At the same time, supplied planting material should be capable of consistently producing good quantities of high quality food oil. In order to undertake this process, proper identification, collection and selection of Allanblackia germplasm is required. In the below sections, we consider each of these in turn, addressing aspects of theory and actual practice on Allanblackia. Key lessons for practical deployment are considered, and key gaps where our current understanding is limited, and where further work is therefore required, are related. 1. Species identification When establishing both harvesting and cultivation programmes for a new tree product, it is important to be able to properly identify the tree concerned. Allanblackia has features (e.g. large fruit, a characteristic flower and a particular tree architecture) that allow it to be distinguished relatively easily from other genera in African forests. More important is the ability to be able to distinguish between different species (apparently nine) within the Allanblackia genus, for the following reasons: Although little is currently known about the oil quality attributes of different Allanblackia species, they are likely to vary. In the future, production will likely focus on better quality species, and distinguishing these from other Allanblackia taxa when they co-occur will be necessary. In order to protect the performance of cultivated stands, the species-identity of material entering cultivation should ‘match’ the identity of trees growing wild in a given area. This is to avoid problems of outbreeding depression (loss of performance because mating trees are too different) when cultivated trees are pollinated by wild stands. In a ‘local’ domestication strategy, in which material for cultivation comes from neighbouring natural stands, no problems should be encountered. However, if germplasm translocations take place over large distances, difficulties may arise if species are not properly discriminated between. Proper circa and ex situ conservation of Allanblackia requires that species identity be accurately applied to natural stands, in order that priorities can be set for bringing material into local cultivation (for circa situ conservation) or into live gene banks (ex situ conservation). If identity is not accurately assigned, ‘rare’ populations may be ‘missed’. In practice, the situation with species identification within Allanblackia is much more straightforward than for many other tree genera. This is because, of the countries currently involved in the Allanblackia initiative, in two (Ghana and Nigeria) only a single species is believed to occur in each, so no opportunity for ‘mixing’ of species arises (see Table 1; except in the event that germplasm is transferred between countries, which currently appears unlikely for Allanblackia). Only in Cameroon and Tanzania do multiple species coexist, with three found in the former country and two in the latter (Table 1). In these countries, species are on occasions sympatric (close or overlapping distributions), a situation where proper identification is particularly important. In practice, however, species normally have rather different ecological requirements and overlapping distributions are limited. For example, in Tanzania, A. stuhlmannii appears to be primarily ‘submontane’ (800 to 1500 m), while A. ulugurensis primarily grows in ‘montane’ or 2 ‘upper montane’ (> 1500 m) regions. Furthermore, there are generally other clear differences between species. For example, in Tanzania, A. stuhlmannii has larger fruit than A. ulugurensis. Cameroon appears to face the most difficult situation for discrimination, since A. floribunda and A. stanerana both widely occur in lowland forest, but fruit size and other features can discriminate between these species. In summary, then, identification of, and discrimination between, different species should be a relatively straightforward exercise in all of the countries currently participating in the Allanblackia initiative. Table 1. Allanblackia species and their apparent distributions in project countries Country Species present Notes on distribution/identity Cameroon A. floribunda A. gabonensis A. stanerana Allanblackia gabonensis is found in ‘submontane’ forest (> 500 m altitude), A. stanerana has identifiably smaller fruit than other species (?) and is found in coastal forest, mostly in west and southwest Cameroon, sympatric in part with lowland forest A. floribunda. Ghana A. parviflora Single species means identification straightforward. Nigeria A. floribunda Single species means identification straightforward. Tanzania A. stuhlmannii A. ulugurensis Sometimes find only one species present on a particular mountain in the Eastern Arc, sometimes find both (e.g. in the Uluguru’s). In the Uluguru’s, although sympatry is possible, A. stuhlmannii appears to be primarily ‘submontane’ (800 to 1500 m), A. ulugurensis primarily ‘montane’ or ‘upper montane’ (> 1500 m). Allanblackia stuhlmannii is distinguishable because it has larger fruit than A. ulugurensis. 2. Collection Within the context of a domestication and sustainable use programme, germplasm collection of Allanblackia is important for a number of reasons, including for: Raising seedling/other propagules for distribution to farmers (farmers may collect their own germplasm or it may be collected for them by an extension or other agency). Tree management research (e.g. on how to germinate seed or vegetatively propagate trees). Genetic improvement programmes (e.g. for the establishment of provenance field trials from which superior material can be selected through exploiting intraspecific variation in a species). Ex situ conservation (e.g. establishment of field gene banks for long-term management of genetic resources). Collections undertaken to date on Allanblackia have used a number of approaches. Material has been sampled as both seed and vegetative propagules, and both random and targeted methods to collection have been adopted. In the below, a brief description of the theory behind the different approaches that have been applied, each of which has potential advantages and disadvantages, is given. 3 2.1. Seed and vegetative collection To date, most large-scale germplasm collections of Allanblackia that have had both practical deployment and research objectives (in Ghana and Tanzania) have been based on sampling seed (see Box 1 for some general guidelines for Allanblackia seed collection). In Ghana, for example, ITSC, in collaboration with local communities, has collected hundreds of thousands of seed from hundreds of trees, for establishment in nursery beds in their central facility at Offinso. Similarly, in Tanzania, for example, ANR and ICRAF have collected and planted hundreds of thousands of seed in nurseries beds at ANR’s central facility and (with TFCG) in medium-scale community nurseries, in the East Usambara. In Tanzania, community nurseries have also become directly involved in seed collection, sometimes adopting innovative methods to sampling and handling that may be of more general relevance to the Allanblackia initiative (such as harvesting from rat caches/burrows, and fruit burial as a seed pre-treatment). Box 1. Some general guidelines for Allanblackia seed collection (taken from current collection and propagation extension guidelines) Time of collection Allanblackia appears to shows one main fruiting season (~ December through February), sometimes with a second more minor fruiting period (~ May through July). Collection is easiest during the main fruiting season (~ December to February). Fruit should be collected from trees immediately after it falls to the ground, to prevent it going mouldy or seed being eaten by animals (repeated regular visits to populations are necessary to maximise collection opportunities). Transportation If transporting material large distances, it is better to transport seed within fruit rather than extracting it at the collection point. During transportation, allow air to circulate between fruit to prevent overheating, and do not expose unnecessarily to sunlight. Processing On arrival at the seed extraction site, store fruit in an open shaded area protected from animals until it can be processed. Extract seed from fruit by crushing between hands and then hand-separate seed from pulp. Bury seed in moist sand until further processing or planting out can be undertaken. It is anticipated that, as the Allanblackia initiative develops, a greater focus will be placed on vegetative- rather than seed-based propagation during deployment. In Tanzania, the collection of vegetative propagules for deployment purposes on a significant scale has already begun: leafy cuttings are currently being collected from 100 mature cut and coppicing female trees in farmland in the East Usambara region, and are being rooted in non-mist propagators (see Box 2 for some general guidelines for Allanblackia vegetative collection). Box 2. Some general guidelines for collecting Allanblackia vegetatively (cuttings) (taken from current collection and propagation extension guidelines; for more details see other presentations from this course) Cutting mature trees for source material Cut mature female trees to a stump height of ~ 75 cm at the start of the rainy season (cutting at this time facilitates re-sprouting). Trees should be cut at a slight angle (about 15 degrees) to facilitate run-off (prevent rotting). Leave trees to re-sprout/coppice, monitoring progress (it may take several months before any material can be collected). 4 Remove the buds of dominant shoots to encourage bushy development of regrowth (provides more material for harvesting). Collecting and handling shoots cuttings Take regrowth that is 2.5 to 12 cm long, with a stem diameter at the base of ~ 4 to 8 mm. Cut from the stock plant using sharp secateurs or a sharp knife. Moisten cut shoots and place them in a plastic bag to prevent them from drying out. Keep the plastic bag in the shade to prevent shoots from overheating. Material should be collected before it becomes too woody, since otherwise it will become more difficult to root. Transportation Transport cuttings to the nursery site as soon as is practicable. This may require a vehicle to move backwards and forwards between collection site and nursery area as harvesting proceeds. Processing On reaching the nursery area, ensure cuttings are placed into non-mist propagators as soon as possible (certainly on the same day as harvested). This requires good prior preparation at the nursery area – with propagators and necessary materials all ready for the receipt of cuttings. Make a new clean cut to cuttings and follow the appropriate procedure for rooting leafy stem cuttings in propagators (see others sessions of this course on vegetative propagation). Seed and vegetative approaches to tree germplasm collection both carry their own advantages and disadvantages (summarised in Box 3 below), some of which are particularly pertinent for Allanblackia (as highlighted). The key advantages associated with vegetative propagation for Allanblackia appear to be accelerated maturation (reduced time to fruiting), control of gender (Allanblackia having separate male and female trees) and the ability to circumvent the difficulties observed with seed germination. A key disadvantage for Allanblackia, when collecting large quantities of vegetative material, is the significant extra resources required during and after collection compared to seed sampling, especially in the establishment and maintenance of non-mist propagators. Box 3. Advantages and disadvantages of a vegetative- compared to a seed-based approach to tree germplasm collection (with particular relevance for Allanblackia in bold) Advantages associated with vegetative sampling may include: Accelerated expression of important characteristics may be exhibited by vegetative material. For example, material may fruit earlier than if sampled as seed. This has advantages both for the evaluation of germplasm in tree improvement programmes and in the direct distribution of material to users. In the latter case, farmers may more quickly receive benefits from collected material. This issue is of particular importance for Allanblackia, with trees established from seed expected to fruit after ~ 12 years, and material propagated vegetatively (leafy cuttings taken from mature females) expected to fruit before the 5th year after establishment. During collection, an exact genetic copy of the sampled tree is taken. This could be an advantage when carrying out selection for superior trees, providing increased efficiency during targeted sampling (see following sections; favourable genes and adaptive gene complexes in mother trees may be lost during the collection of seed because the pollinating parent is unknown). Collection of an exact copy also means that the sex of propagules taken from dioecious trees is known, which is an important consideration in efficient management of such species. The ability to control sex during the collection of Allanblackia planting material is significant, because it allows more female than male trees to be planted on farms. This should allow greater unit area productivity from planted stands. Collection is possible when no seed is available or where seed handling is difficult. For some species, the appropriate time for fruit collection may be difficult to predict and may vary greatly between years. Some species may not fruit in some years, or, if outbreeders, be unable to produce fruit at all, due to genetic isolation as a result of population fragmentation. In these instances, the ability to collect vegetative material provides the only method of obtaining 5 germplasm. Seed of fruit trees in particular can sometimes be difficult to handle, making vegetative propagation an attractive option. This issue is particularly relevant for Allanblackia, the seed of which can take considerable time to germinate, with low absolute levels of germination sometimes also observed. In addition, Allanblackia seed must be collected at just the right time, which requires careful (and sometimes difficult) synchronisation (when fruit has fallen from trees, but before it is eaten by animals). Disadvantages associated with vegetative sampling may include: Vegetative collection may suffer from practical difficulties. The techniques involved in collection may be difficult (possibly requiring considerable prior research for optimisation) and time consuming. Vegetative material is perishable – it must therefore be handled carefully in the field and can not normally be stored for long periods of time. Material may be bulky and difficult to process, requiring special equipment such as nursery propagators. Regulations on germplasm movement may be stricter when compared to seed, due to the increased potential for the transmission of viruses or other diseases. The need to build thousands of non-mist propagators for rooting of germplasm collected as leafy stem cuttings is a particular practical issue for Allanblackia. Vegetative sampling is often combined with a targeted approach to germplasm collection, but the effectiveness of selection from natural stands is not well known (this issue is addressed further in the following sections). Vegetative collection tends to focus on a small number of trees from any given provenance. Likely, this leads to a narrowing of the genetic base in collected material. Although reduced genetic variation may be an advantage in certain situations (e.g. when markets require a product of uniform size and character), it may also lead to a reduced capacity of germplasm to adapt to varying environmental conditions or user requirements. One approach to avoid a narrowing of the genetic base during vegetative sampling is to collect, evaluate and distribute a greater number of clones from provenances. However, this practice has rarely been followed. In the case of Allanblackia, genetic narrowing is unlikely to be a major issue simply because of the very large numbers of propagules required in project countries, which will require that material is cloned from many different trees. Apart from collection via seed and vegetative means, some more minor collections based on wilding transplantation have also been successful. This is particularly the case in Tanzania, where community nursery groups around ANR have transplanted Allanblackia wildings into nurseries very local to forest sampling sites, using locally collected forest soil as the potting substrate. Wilding collection may provide a ‘stop-gap’ method while seed and vegetative propagation approaches are further developed, but it is unlikely to become a major collection approach in the Allanblackia initiative, and is not considered further in this session. 2.2. Random and targeted sampling Germplasm collections of Allanblackia to date have used both ‘random’ (or ‘random systematic’) and ‘targeted’ approaches during sampling. In the former case, this means that no efforts to undertake selection during collection were made; rather, seed was just sampled ‘at random’ (with certain spacing criteria) from any trees within a given population. An example of this is the collections that ITSC has made with local communities in Ghana, in order to raise seedlings for practical deployment purposes. In the second case, of ‘targeted’ sampling, this means that certain selection criteria were applied during collection (see Dawson and Were 1997 for further definition of terms). Targeted approaches have been applied (so far at a relatively low intensity) to both Allanblackia seed and vegetative propagule collection. For example, in Ghana, FORIG has sampled seed from ‘superior’ fruit producing trees (those trees that based on visual observations during collection appeared to be ‘heavy’ yielders – it appears that fruit size and seed yield are related, see more in next section) when collecting material for field trials and for ex situ gene bank establishment. In Tanzania, seed collected for nursery establishment by ANR and ICRAF also 6 came from trees that were selected as superior producers. In addition, trees cut down for vegetative sampling in Tanzania (on farms around ANR) were chosen as superior yielders. Speaking generally, random and targeted approaches to tree germplasm collection have different potential advantages and disadvantages. These must be considered carefully before collection begins, in the context of an overall domestication strategy for a particular species. Table 2 highlights some of the advantages and disadvantages of the different approaches, in terms of collection of germplasm from a given population. Table 2. Some potential advantages and disadvantages of random systematic and targeted approaches to germplasm collection from a given population Strategy Random systematic sampling Targeted collection Advantages Disadvantages Collection is representative of the population as a whole, allowing accurate comparisons of populations in field trials Collection samples the widest possible genetic base, providing an adaptive capacity to varying farmer requirements and changing environmental conditions, and preventing future inbreeding depression Recollection using a similar strategy will result in material of approximately the same composition and performance. Because representative of a population, the approach is considered ideal for ex and circa situ conservation purposes Random systematic sampling can be time consuming because it involves collecting from many trees May end up collecting material of low quality that has little utilisation value May be more likely to collect superior germplasm, for improvement purposes (if heritability of targeted characters is high; see below) Targeted sampling provides greater opportunities for the involvement of communities in collection, providing a link into village-level, communityoriented, tree domestication strategies Phenotypic selection may not be effective in the field. Valuable time and effort may thus be placed on identifying ‘superior’ trees that are in fact little different from randomly sampled individuals, unless selected traits are of high heritability and easily quantified (see below) Collection may not be representative of a population, making future recollections difficult unless excellent documentation is kept on individual trees sampled (marking, accurate georeferencing) Possible narrowing of genetic base, with negative consequences for long-term sustainable resource management With indigenous fruit trees, despite some potential drawbacks (such as the effort needed to properly identify superior trees and difficulties in re-sampling from populations unless proper records are kept), recent emphasis has tended to be on targeted rather than random collection of germplasm. This is for three main reasons: First, it is felt that the heritability of traits important in fruit production is reasonably high, meaning that selection from natural stands is possible (but see section below on selection). 7 Second, many fruit tree species are collected vegetatively, where it is felt that targeted selection approaches are more likely to be effective than during seed collection (see above and below); and Third, the linkage that community-based targeted sampling can bring into the adoption of the wider village-level domestication strategies that are becoming popular for indigenous fruit trees is an important one. By involving communities in selection for traits that they are concerned with, their interest in engaging in tree domestication generally is enhanced, facilitating potential for adoption. In the case of Allanblackia, the above three points hold true to varying degrees, depending partly on the country in question (the adoption of village-level indigenous fruit tree domestication strategies is currently more prevalent in Cameroon/Nigeria than in Ghana/Tanzania). 2.3. General features important in collection Irrespective of the approach used to sample germplasm, certain key issues are important and should be incorporated into any tree germplasm collection process, including for Allanblackia seed or vegetative material. Some important issues are listed in Box 4. Box 4. General issues important during germplasm collection (see Dawson and Were 1997) Construct a proper rationale for collection A well-developed written rationale describing the purpose of collection and the methodology that will be used during sampling is essential before any collection commences. In addition, the next steps in the use of collected material need to be clearly described. Find out where to collect from Prior research of herbaria, literature and key knowledge holders, combined with preliminary field work, are necessary to determine from where, when, and how, germplasm can be collected. Arrange logistics A team with the appropriate skills for collection must be assembled, with the necessary equipment for collection and field processing, as well as the necessary permissions for collection from the relevant authorities. Document the process Good written documentation during and after collection, for future reference, is essential for engagement in an efficient domestication programme. It may be necessary some years in the future to return to particular populations or particular trees for further sampling and evaluation. This is only possible if proper records have been kept. This is particularly important for targeted vegetative sampling. Maintain biological standards during collection What standard to adhere to during a particular sampling exercise depends on the purpose and strategy behind collection. However, remember that, when collecting seed, this must be collected at the right stage of physiological maturity. In addition, sampling from a minimum of 30 trees is required in order to effectively ‘represent’ a population genetically. If collections are to represent available genetic variation within a species or country, a number of sites also need to be sampled. Ensure efficient processing to feed into future use During and after collection, germplasm should be processed in a manner that optimally maintains viability and allows material to feed efficiently into the next stage of the designated use for sampled germplasm. When material is designated for research purposes, seed should normally be kept separate by individual trees during processing. Be flexible Every collection has unique features and problems. Collectors must be flexible and pragmatic, rethinking strategy in the field depending upon the conditions they encounter, and understanding where compromises can, and can not, be made. 8 3. Selection of superior planting material As mentioned in the previous section, ‘targeted’ seed and vegetative collections of Allanblackia germplasm have been undertaken. This has been done in an effort to secure genetic gains that can provide added productivity for farmers during practical deployment, and to provide good starting material for tree improvement programmes (field trials). In this section, we discuss in more detail the basis for selection in Allanblackia and relate how effective current practice is likely to be in providing superior material. 3.1. The basis for selection Selection can only be effective if significant genetic variation exists within Allanblackia, from which choices can be made. Observations on natural stands, particularly in Cameroon, do indicate that significant morphological variation in fruit yield characteristics exists within populations of particular species, between populations of a given species, and between species, suggesting potential for selection exists at all three of these levels. In particular (as is typical for many tree species), considerable variation exists within populations; in one population of A. floribunda in Cameroon, average seed weight per fruit varied by more than a factor of four between best- and worse-performing trees (see Figure 1). More importantly, the same study detected significant variation in total seed weight per tree, and that measurements on seed weight per fruit were positively correlated with fruit dimensions, meaning that it should be possible to use fruit size as a proxy for selecting trees with the more important attribute of high seed yield. These observations provide some basis to believe that selection approaches can be applied effectively during the collection of natural stands of Allanblackia. Fig. 1. Selection issues. Tree-to-tree variation in seed weight per fruit for A. floribunda trees sampled at the Yalpenda site, Cameroon Average total seed weight per fruit per tree (g) 450 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 Tree Values of average total seed weight per fruit per tree are shown for 57 trees, based on one seasons observations, with measurements based on 40 fruit per tree. Values varied widely between trees, and differences between ‘low’ and ‘high’ producers were statistically significant. Source: ICRAF Cameroon 9 3.2. Current selection practice and likely effectiveness Selection of Allanblackia to date has been based on single sets of observations (made at the time of collection) on fruit size and yield in natural stands, these characteristics being assumed to correlate positively with seed yield. Selection has been applied during both vegetative sampling (primarily of leafy stem cuttings) and seed collection. In the latter case, targeted sampling has been applied to more than 350 selected trees across the four countries involved in the Allanblackia initiative. As mentioned in the previous section, selection is likely to be more effective when a vegetativerather than seed-based approach to collection is applied, because in the former case an exact genetic copy of the sampled tree is taken, while in the latter case only the ‘maternal’ component is sampled (the ‘father’, the tree pollinating the fruit from which seed is actually sampled, is unknown and unselected). Even in the case of vegetative sampling, however, there are questions about the efficacy of phenotypic selection as currently applied to Allanblackia. Two of the relevant issues are summarised below: Environmental differences When carrying out selection based on observations in natural stands, it is impossible to eliminate the ‘environmental’ contribution to phenotypic differences. For example, particular trees may yield more because they grow near water or in other niches that are particularly fertile. Differences based on such factors are not heritable and therefore will not be carried over into subsequent generations of material derived from ‘superior’ trees. Environmental effects can only be eliminated in controlled field trials, and this is one reason why such trials remain important for the selection of superior material. Pollinator action Differences observed between trees in fruit production in any given year may reflect in part the ‘vagaries’ of pollinator activity and movement during the particular season in which observations are made. Observations made in another season may rank the performance of trees differently. Ideally, observations need to be made over a number of years in order to apply efficient selection, although discussions with farmers (which trees perform well consistently?) can help in this process. Despite these concerns, it seems reasonable to assume, based on experiences from other indigenous fruit trees, that some level of selection is possible during collection from natural Allanblackia stands, even when selection is based only on a single round of observations. This is especially the case when a vegetative approach is used, which is also favoured during Allanblackia collection for other reasons (as addressed in the previous section). The level of gain, however, may be lower than many collectors would anticipate, especially if germplasm is sampled as seed. The benefits of selection in this instance may not always outweigh the extra costs incurred (in particular, the extra time and effort required to make, record and mark selections). 4. Current best practice and gaps to be addressed 4.1. Practice and gaps for collection Methods to collect Allanblackia germplasm, based on sampling of seed, vegetative propagules and wildings, have been developed and are in place. All can fulfil a useful role in collection, depending on the context in which sampling is placed, although vegetative sampling in the future is likely to be the dominant approach. Using seed, vegetative and wilding approaches to 10 sampling, germplasm of Allanblackia has been collected for distribution to farmers, for management research, for field trials and for conservation. Seed collection relies on sampling mature Allanblackia fruit from the base of trees before they are attacked by animals or can go mouldy, and requires proper documentation of activities for future reference. Collection via vegetative techniques has proved possible, with good success achieved in rooting leafy stem cuttings taken from cut mature females. Studies indicate that wilding transplantation is also an alternative method for germplasm collection, if due attention is given to potting medium and reducing stress during translocation. Further information on best practices for seed germination, for vegetative propagation and for wilding transplantation is given in other sessions of this course. Particular points to note during the collection of Allanblackia are: Vegetative sampling carries certain key advantages compared to seed sampling. These relate to accelerated maturation, control of gender and the ability to circumvent difficulties observed with seed germination. An important disadvantage, though, is the significant extra resources required during and after collection, especially in the establishment and maintenance of non-mist propagators. Targeted collection of Allanblackia germplasm is likely to be worthwhile in certain circumstances because of the genetic gains it may bring, especially when linked to vegetative sampling. The targeted approach provides a good linkage into wider village-level domestication strategies, by meaningfully involving communities in collection. Considering gaps in current knowledge, particular points to be addressed are: Although methods for collection based on seed, vegetative and wilding sampling are available, the efficiency of these approaches is not always high, and currently very variable across locations. Continual modification in best practice at all project sites, based on emerging knowledge on how to handle the genus, is required. The efficacy of targeted compared to random sampling is unknown and is a research question that needs to be addressed in field trials that compare both vegetative and seed material collected using both approaches (particularly important for material sampled vegetatively, since this collection approach is likely to be the dominant one, in the future). 4.2. Practice and gaps for selection Large variation between trees in fruit production is observed in Allanblackia populations, suggesting the utility of selection for bringing genetic gains. Selection of ‘superior’ germplasm has been carried out in natural stands based on a single round of observations on fruit yield made during seed collection (or at the point of cutting trees down for re-sprouting, in the case of vegetative sampling). Particular points to note during selection are: Experience from other tree species suggests that selection should be possible from natural stands. However, because of environmental effects and vagaries in pollination, selection may not be as effective as collectors may at first anticipate. Selection is likely to be more effective when applied to vegetative collection (the approach anyway favoured for Allanblackia for other reasons), because in this case an exact genetic copy of the parent tree is taken. 11 Considering gaps in current knowledge, there are a number or important issues that need to be addressed for Allanblackia selection. These include the following: To date, selection has been based only on overall yield characteristics. Other important traits for selection could include either a ‘spread’ or ‘contraction’ of the fruiting season (depending on competing labour requirements for other crops), the generation of more stable production types (reduced ‘mast’ fruiting); and types with more optimal oil composition (e.g. reduced natural ‘spread’ in composition around the ‘ideal’ profile). Of these characteristics, stability of production is probably the most crucial. Important characteristics for selection may depend on the particular requirements of the different communities in which the Allanblackia business becomes established. This means that a certain amount of flexibility in trait selection may be required, and that at different sites a process of participatory priority setting for determining important characteristics for improvement may be necessary. It is not clear yet how practical such an approach will be. 5. Bibliography Dawson I, Were J (1997) Collecting germplasm from trees. Agroforestry Today, 9 (2), 6-9. (On course CD-ROM as PDF file.) FAO, Forestry Resources Division (1995) Collecting woody perennials. In: Guarino L, Ramanatha Rao V, Reid R (eds.) Collecting Plant Genetic Diversity: Technical Guidelines. CAB International, Wallingford, UK. pp. 485-489. Roeland Kindt (2006) The Tree Seed Toolkit. ICRAF, Nairobi, Kenya. (A resource describing many of the issues related to tree germplasm management, from technical guidelines on sampling through to advice on small-business establishment for collectors. Available as CDROM during the course.) 12