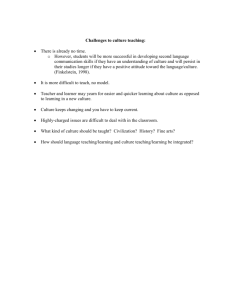

The mysteries of intercultural communication

advertisement