Since the first excavation seasons at Tel Hazor, led by Yigael Yadin

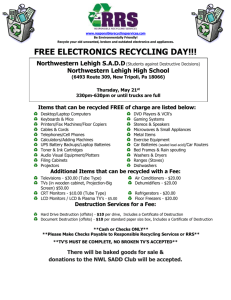

advertisement

1 The Kingdom of Hazor in the Late Bronze Age: Chronological and Regional Aspects of the Material Culture of Hazor and its Settlements Sharon Zuckerman, Institute of Archaeology Since the first excavation seasons at Tel Hazor, led by Yigael Yadin in the 1950’s, impressive remains of fortifications, temples and public buildings from the Bronze Age were unearthed throughout the huge 800 dunams of the upper and lower city of Hazor. The final reports of Yadin’s team are an invaluable source of both architectural and artifactual information relating to the Bronze Age strata, although some of their conclusions have been debated. The renewed excavations at the site have concentrated in two areas on the upper tel: area A, the acropolis, and Area M, on the northern slope of the tel facing the lower city. The Late Bronze Age remains revealed in these two areas and their interpretation are the subject of my dissertation. One aim of my work is to suggest an archaeological and historical reconstruction of the Kingdom of Hazor during the Late Bronze Age II, The last phase of the flourishing Canaanite city. The second aim is a reassessment and renewed discussion in the final destruction of Hazor in the end of the Late Bronze Age. This destruction was extensively discussed, usually in relation to the vivid biblical description of the fire set to the defeated Canaanite metropolis by the Israelites. I intend to discuss the destruction Hazor from a different perspective, evaluating it as the final phase of a long process of development and decline of the mighty kingdom beginning in the Middle Bronze Age. Based on a critical evaluation of previous dating suggestions of this event, I offer evidence for a date that will suit best all kinds of dating evidence available to-date. The detailed stratigraphic analysis of the monumental buildings excavated in the renewed excavations is the basis for a new interpretation of the Acropolis plan during the Late Bronze Age. The building termed "Canaanite Palace", on the highest point of the Tell, should in my opinion be interpreted as part of a large complex of cultic ceremonial buildings arranged around a central courtyard. The activities taking place in the "Canaanite Palace" probably included ritual food consumption on a large scale, as evidenced also by the faunal remains from the 2 courtyard. Another building, on the northern slope of the Tel, is defined as a "Royal Portal" to a spacious building, the residential palace of Abdi-Tirshi king of Hazor and his dynasty. Such "Royal Portals" were found in other Syrian Palaces (notably that of Ugarit) and were probably not open to the public, but served royal emissaries, foreign merchants and other privileged functionaries. These were accepted there by the king or his high officials, participated in a series of ritual activities such as libation or ablution, and than led into the royal palace itself. A major contribution of the ceramic assemblage is Chronology. Some types of vessels are chronologically indicative, and point to a date early in the 13 th century BC for the final destruction of Canaanite Hazor. The date and causes of the violent destruction of Canaanite Hazor have been an important issue ever since the first excavations of the site. The different suggestions for dating this event can be categorized under two separate schools. The first school dates the destruction to the later half of the 13th century, sometime during the last years of the long rein of Ramses II or his heir Merneptah. These scholars (noteworthy are Yigael Yadin, Yohanan Aharoni, and Amnon Ben-Tor), tie the destruction of Canaanite Hazor to the biblical descriptions in Joshua and see the Israelites as responsible for this event. The second school tends to support an earlier date in the first half of the 13th century. Proponents of this date, such as Olga Tufnell, Kethlyn Kenyon, P.Beck and M.Kochavi and Israel Finkelstein, base their suggestions on the preliminary study of the pottery of Hazor and its connection to the ceramic assemblages of dated sites. In my dissertation I evaluated all lines of evidence that can contribute to the chronological debate. These include imported Wares (mainly Mycenaean pottery), Egyptian historical sources and finds at Hazor, cuneiform tablets found in the destruction level and C14 dates of samples from the same context. Most of these support the earlier date suggested, and point to the first half of the 13th century in the time of Ramses II as the most plausible date for the final destruction of Canaanite Hazor. If this is the case, there is no necessary connection between the destruction of Hazor and the process of Israelite Tribes settlement in Cannan. The destruction of Canaanite Hazor should be studied as the last phase of a long process of development, flourishing and decline of the kingdom. The remains of the activities taking place in the two monumental complexes on the upper tel provide important clues both to the strength of Hazor and the seeds of its decline. Large-scale ritual 3 meals can be reconstructed on the basis of the ceramic and faunal assemblages in the “Canaanite Palace” and its courtyard. These commensal feasts could have served as the city’s elite way of labour recruitment, needed for the large scale building activities in the beginning of the 14th century BC. It can thus explain Hazor’s special status in its Canaanite context. The remains of such ritual feasts in the last phase before the destruction should be explained against the background of deteriorating political and economic conditions and the growing competition between the Canaanite city-states. The destruction of Canaanite Hazor was violent but selective. Remains of fire were limited to the temples in the lower city and the monumental buildings on the Tel. The destruction campaign was thus aimed at centers of political and religious power in the city, and the destruction of gods and kings statues should be seen as part of this attack against the ruling hierarchy. The dwelling quarters in the lower city were not affected. The bearers of such destruction could have well been other Canaanite hostile city or even the city dwellers themselves, so long suppressed under the ruling authority. Whoever was responsible for this event was not interested in the rebuilding of the city, and the city was deserted. Its population probably spread to other sites in the vicinity, which continued to flourish in the second half of the 13th century. Hazor was left deserted for a certain period and lost its role as a major center for decades to come.