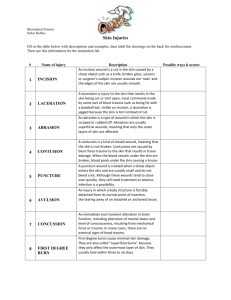

Clinical case

USC Case # 15: Laceration and Suturing

Case 1

CC: 17 yo female cut with scalpel during biology class

HPI: A local high school student familiar to your practice presents to the office with a laceration to her right hand 30 minutes ago. It is 6cm long. She has it wrapped in paper towels. It has stopped bleeding for the most part. She has no history of lacerations. She has full range of motion in the hand,

1. What are the first steps to dealing with this issue?

2. The patient does not remember her last tetanus booster shot. What should you do?

3. The patient confides in you that she is 12 weeks pregnant and that her parents are unaware. She does not want you to tell them. What should you do if she needs a booster shot? How does the pregnancy affect your decision to provide her this booster shot?

4. Which wounds have the highest risk for contracting tetanus?

5. The patient states she does not believe in vaccinations and refuses the booster you recommend. What are your responsibilities in this case?

Answers:

1) The first issue is always informing the patient of what you need to do to take care of them. In this case you need to discuss wounds in general, determine tetanus status(see below), determine allergies to local anesthetics or cleansing solutions and obtain informed consent for what you intend do for the wound, including cleaning and repairing it. If after examining the wound you determine it is above your comfort or skill level to repair, referral to a proper specialist is indicated (this will be discussed further below).

2) With any wound you need to discern the patient's tetanus status. The recommended interval between tetanus booster is every ten years. However, in the case of a new wound it is common practice to administer a booster if it has been five years or less. At this particular patient's age (17) she would normally have received her last office based booster at age 11-15. If it has been more than five years since their last booster shot you should administer one.

3. Pregnant women need to be immunized against tetanus. Unvaccinated pregnant women should receive two doses of Td and previously vaccinated women should receive a booster. There is no danger of harming the fetus by vaccinating the mother.

Communicating pregnancy status of minors to their parents or guardians is another matter and beyond the scope of this paper.

4. Wounds with dirt, feces or saliva have the highest risk for tetanus. "rusty nails" are the stereotypical example, but these three examples are equally important to consider.

5. Your responsibilities to her as her doctor come down to informed consent. If she refuses the booster she needs to understand the risks of doing so. It is good practice to have the patient (or in a minor's case, her parent or guardian) sign a form indicating they have been informed of the need for the booster and they refuse it and accept responsibility for doing so.

During your examination of the wound you find that it penetrates into the subcutaneous fat. Muscle and tendon testing of the extensor mechanisms in the hand show no deficits.

She has full neurological sensation in the hand and fingers. The wound is still trickling a small amount of blood.

1) What should you do next?

2) What are the steps to examining a laceration and wound?

Answers:

1) Providing the patient comfort during a procedure is very important. It is surprising the number of times this is not addressed. In the case of a laceration or wound one of the best ways to do this is the applying local anesthesia to the area involved. The sooner this

can be done the sooner the patient can start to relax. This can be done with topical agents or local infiltration of anesthetics (see below). Cold compression ice bandages also work.

Establishing hemostasis is the next step. Direct pressure is the first method usually employed. Even if a wound has stopped bleeding it will oftentimes rebleed during the anesthetizing or suturing phase. Sometimes you will need to use a chemical or electric cautery to stop the bleeding. Tying off deep bleeders also will work.

2) Examining a wound involves first making the patient comfortable with local anesthesia. Once the pain is gone the patient will more likely relax. Start by gloving up and opening the wound, looking for foreign bodies such as dirt, stones, glass, metal, tree bark, etc. A good history is likely to uncover what you can expect to find in the wound.

Be careful about blind sweeps with your finger in a wound where you expect to find sharp objects such as glass or metal.

Once all debris has been removed, irrigate it with copious amounts of sterile saline.

There is a saying that reads "the solution to pollution is dilution". This should be self explanatory. Always ask the patient about allergies to cleansing agents such as iodine. If this exists then chose clorhexidine or another agent free of iodine. Lastly, dry the wound and drape it off so that only the area where you are working is exposed. This keeps the needles and suture material from coming into contact with the contaminated, non-sterile surrounding areas such as the exam table, other body areas, hair, etc.

Once the wound has been closed, however, the occlusion of the wound itself will act to keep the bleeding at bay. Using a local anesthetic that contains epinephrine promotes vasoconstriction and subsequent hemostasis. There are certain areas of the body where it has been common practice to avoid the use of epinephrine including the ears, nose, finger, toes and penis. The theory behind this practice is that these are areas with terminal blood supply and vasoconstriction could promote ischemia and possibly tissue necrosis. However, it has been my experience that physicians who work on these areas regularly (podiatrists, urologists, surgeons) are comfortable using it.

Choosing an anesthetic involves knowing the drug's onset of action and half life.

Always ask the patient about a personal or family history of unfavorable reactions to specific anesthetics. Each of the common local anesthetics below can be given with or without epinephrine.

Table 1

1

Table 1. Common agents used for local anesthesia

Agent Concentration Relative potency

Onset of action with infiltration

Onset of action with nerve block

Duration of action with block

Maximum one-time dose

Lidocaine 1% 2 Fast 4-10 min

60-120 min

4.5 mg/kg

(30 mL in average [70kg] adult)

Mepivacaine

(Carbocaine,

Polocaine)

1% 2 Fast 6-10 min

90-180 min

7 mg/kg (30 mL in average [70kg] adult)

Bupivacaine

(Marcaine,

Sensorcaine)

0.25% 8 Moderate 8-12 min

240-480 min

2 mg/kg (50 mL in average [70kg] adult)

Once the anesthetic has been chosen, the amount drug and type of needle with which to inject it should be determined. The important needle dimensions are 1) the size or

"gauge" of the needle bore and 2) the length of the needle itself. Needles range in size from 14 gauge (very large - used for aspirating joints, etc.) to 30 gauge (very tiny - used for infiltrating wounds). The most common size used are between 18 and 27 gauge.

Needles range in length from 1/2" to 1 1/2". The shortest needle that will reach the desired area should be used because shorter needles are easier to control. You will find a group of needles you prefer using after getting some experience.

Starting at one area of a wound (usually a corner), anesthetize it by infiltrating the drug in to the dermis. Then, use that area as a starting point and numb the remainder of the area through that site to reduce the number of needle sticks a patient feels. Make sure to include all levels of a wound (superficial and deep), as a patient who suddenly feels the suture needle halfway through the procedure will not be happy. Pay close attention to your attending physicians while you are learning this skill - you will develop your own personal technique during this process.

Anesthetizing children's wounds is a skill in itself. Children under 5 and older kids with large wounds or high levels of anxiety are difficult to reason with when a needle is headed their way. If the wound is simple then EMLA

(Eutectic Mixture of Local Anesthetics) cream is a good topical choice. This anesthetizes the wound fairly well prior to the introduction of needles. Sometimes ethyl chloride can also be used for temporary topical anesthesia prior to the use of needles.

Finally, once the wound is cleaned, anesthetized, and draped, you may begin to close it.

Certainly, entire books are written on this subject and this paper should only be used as a brief introduction to the subject. Remember that the scar you leave is all that the patient

will see, so underlying work will be forgotten long before the outer scar. Do your best to suture in a way that produces the best cosmetic result for your patient.

The first question to ask is do you want absorbable or non-absorbable sutures? Knots that will be buried in the deep part of a wound should be absorbable. This is for closing structures such as fascia, muscles and subcutaneous fat. Sometimes non-absorbable suture will be left in the thick fascia or in tendon repairs, but in general deep sutures should be down with absorbable material. Knots that will be visible from the outside or only in temporarily should be non-absorbable. There are exceptions to this rule that you will learn through your training.

The next question is what size of suture to use. In general, the larger the diameter the stronger the suture. However you should strive to use the smallest diameter that will hold the wound together. The larger the number on the suture the smaller the diameter of the material. For example, a 3-0 suture is larger than a 6-0.

Types of sutures

Properties of some absorbable and non-absorbable suture materials

2

Material

Trade name

Natur al or synth

Filament

Effec tive woun d supp ort

(days

)

Absor ption time

(days)

Handling character istics

Tiss ue react ion

Absorbable sutures

Catgut acid

Polyglycolic

-

®

Dexon

Natur al

Synth etic

Multifila ment

Monofila ment

Braide Synth Multifila

8-9

21

21

30

90

90

Poor knot security, high memory

Very poor

Stiff, difficult to handle, but excellent knot security

Mini mal

Better Mini

d

Dexon etic ment handling

, excellent knot security mal

Dexon

®

Vicryl

®

Polyglactin

910

Vicryl

Rapide

®

Poliglecaprone

25

Monocr yl®

Synth etic

Synth etic

Synth etic

Multifila ment

Multifila ment

Monofila ment

Polyglyconate

Polydioxanone

Maxon

®

PDS

II®

Synth etic

Synth etic

Monofila ment

Monofila ment

21

10

20

28

60

90

42

28

180

210

Good

Good

Mini mal

Mini mal

High

Memory

Stiff and difficult to handle

Stiff and difficult to handle

Mini mal

Mini mal

Mini mal

Poly- (llactide/

Glycolide)

Panacr yl®

Synth etic

Multifila ment

60% Wound strength maintained at 6 months

Non-absorbable sutures

Nylon

Ethilon

®

Nurolo n®

Synth etic

Synth etic

Monofila ment

Multifila ment

-

-

Good

Mini mal

Excellent elasticity

, but high memory

Mini mal

Excellent elasticity

, but high memory

Mini mal

Polyester

Polybutester

Mersile ne®

®

Ethibo nd®

Novafil

Synth etic etic

Synth

Synth etic

Monofila ment

Multifila ment

Monofila ment

-

-

-

Excellent

, but significa nt tissue drag

Excellent

, but significa nt tissue drag

Low tissue drag, elastic

Mini mal

Mini mal

Mini mal

Poly

(Hexafluoropr opylene-VDF)

Pronov a

Synth etic

Monofila ment

- Good

Mini mal

Polypropylene

Silk

Prolen e®

Mersilk

®

Virgin

Silk

Synth etic al al

Natur

Natur

Monofila ment

Multifila ment ment

Multifila

-

-

-

Slippery, high plasticity

, poor knot security

Mini mal

Excellent

Excellent

Very poor

Very poor

Types of stitches

Simple interrupted suture

Probably the most common type of stitch. You must keep them evenly spaced. Do not place them too tight or too close together - doing this cuts off blood supply to the healing skin.

Buried interrupted suture

The same rules go for this stitch. Always make sure the actual knot is places facing into the wound so that is does not migrate up and out through the skin. Look at the position of the needle tip in this diagram to see where the knot ends up.

Vertical Mattress

This is a great stitch for providing strength to large wounds which might otherwise come open when a lateral strain is placed across a healing wound. See the diagram below for a step by step diagram of placing this type of stitch. Wounds heal by contracting, and this particular stitch pulls the edges up and away from the wound. As the wound contracts, the edges will be pulled down and the wound in theory should lay flat once healed.

FIGURE 1. The far-far, near-near technique for vertical mattress suture placement. (A) The needle is initially placed forward in the needle driver for a right-handed physician and is passed through both wound edges for the far-far pass. (B) The needle is then placed backwards in the needle driver. (C) The near-near pass is performed with the needle passing within 1 to 2 mm of the

wound edge. The depth of the near-near pass is within the upper dermis, or about

1 to 2 mm deep. (D) The knot is tied over the wound edge, where the initial pass of the suture was placed. (E) Wound edge eversion is achieved through a row of vertical mattress sutures.

Sometimes you may combine different types of stitches such as a vertical mattress and interrupted suture, such as below:

Horizontal Mattress

This is another good stitch to provide strength to a wound. Longer wounds benefit more from this because the tension is dispersed along the length of the stitch.

FIGURE 2.

The horizontal mattress suture. (A) Initially, the needle is passed across the wound. (B and C) The needle is placed backwards in the needle holder and moved down the wound edge before it is passed back to the original wound edge. (D)

The threads are tied to complete the horizontal mattress suture.

Corner Suture

This can be a challenging stitch to place, but if approached correctly can result in a favorable cosmetic appearance.

FIGURE 6.

Corner suture. (A) To begin the corner suture, consider drawing a plumb line that bisects the angle opposite the corner wound that will be closed. Insert the needle next to the line. The needle is passed into the wound in the level of the deep dermis, 4 to 6 mm from the corner. (B) The corner flap is elevated with Adson forceps

(pick-ups), and the needle is passed from one side of the flap tip to the other side in the deep dermis. (C) The needle then passes back into the wound edge about 4 to 6 mm from the tip and (D) exits the skin. The suture thread passing to and from the corner flap is elevated by the needle driver for demonstration purposes.

When to remove sutures or staples

Area Removal time (days)

Face

Neck

3 to 5

5 to 8

Scalp

Upper extremity

Trunk

7 to 9

8 to 14

10 to 14

Extensor surface hands 14

Lower extremity 14 to 28

Caring for a repaired wound

Educating your patient about how to care for their wound is as important as placing them in the first place. Always have them monitor the wound for signs of infection such as pain, swelling, fevers and chills, purulent discharge from the wound and pain in collections of lymph nodes proximal to the wound such as the axillae, groin, neck, etc.

Encourage the patient to call immediately is these signs appear. Regular inspection and bandage changing can help the wound stay clean and heal faster.

Encourage patients to take a multivitamin a day while the wound heals. The zinc, vitamin C and other nutrients will help the healing process. Make sure your diabetic patient's blood sugars are well controlled for the same reason. Lastly, smoker's wounds

(as well as their bone fractures and other healing processes) heal much more slowly than nonsmokers. Encourage them to stop at least while the wound heals.

When a wound is closed initially it makes sense to put a small amount of topical antibiotic on it. This can help the infectious potential. However, discourage the daily application of these same topical ointments such as Neosporin, etc after the initial procedure. People put these on for two reasons; 1) to "keep the wound moist" and 2) "to keep infection away". To address these points, 1) wounds need to be dry to heal, not moist. Wet wounds take longer to heal. 2) If a wound becomes infected, the patient needs at least oral, sometimes IV antibiotics. No studies have shown that topical antibiotics placed daily on a wound help lower infection rates. Lastly, the other nonantibiotic components of compounds such as Neosporin cause a lot of regional allergic reactions. This is another reason not to use them.

Surgical Staples

Wounds can also be closed with sterile staples. These are easy to apply and close the wound quickly. They tend to work well in certain areas, especially the scalp. They do produce a "train track" appearance as the scar heals though, which is not as big an issue under the hairline. Physicians will have varying opinions on the merits of staples as you go through your training.

New advances in laceration repair

Skin adhesive

Dermabond is a new type of "skin glue" which supplants the need to suture small wounds. Its advantage is bypassing the need for anesthetic or suture material. It is particularly helpful in the pediatric population. You must have a very clean and well approximated wound for this to work though. It stays on for approximately 14 days and then comes off on its own.

Learn your skills, have confidence and know your limits

Through your training, learn as many skills as you can, including suturing. Too often primary care physicians refer procedures to specialists when they themselves can do the work. Usually this stems from training institutions that do not promote resident procedures or resident confidence. Also, if you train in an institution with many subspecialists, each group will try to lay claim to a certain number of procedures. Some of

these make sense, others do not. That being said, there are some specific types of wounds that should be cared for by specialists.

Referable lacerations include, but are not limited to the following:

1) Lip lacerations that cross the vermillion border (where the lipstick ends on the picture below). If this area is not lined up well during the closure it can result in cosmetic issues.

2) Neck lacerations that violate the platysma muscle. This is because of the extensive underlying neurovascular structures. The platysma muscle is quite superficial to the dermis and subcutaneous fat - see below.

3) Facial lacerations in young women and children. You must know your patient well to suture these areas. Some patients will be absolutely fine with you doing this. Others will demand to see a plastic surgeon - do not fight this. If you talk a patient into this or any other procedure and they have a bad outcome, you will be held responsible. As you gain experience you will become more and more comfortable with your abilities.

4) Suturing burned or crushed areas. The problem here is that tissue has become, in many cases, devitalized, and necrosis can set in. Tissue flaps raised and placed by a surgeon is the best approach in this case.

5) Wound that have been open for more than six hours. These also need surgical attention because of the debridement, irrigation and close inspection that is required for good care.

6) Through and through laceration of the eyelid or eyeball.

7) Some deep lacerations of the nose and ear. Again, there can be cosmetic issues with repairing these regions.

8) Deep lacerations involving tendons or into joint spaces.

9) Laceration overlying fractures - if the wound is contaminated or there is exposed bone then always involve a surgeon.

10) Tattoos - individuals with tattoos are very sensitive to having them altered, even in the face of a major wound. Offer to have them seen by a surgeon to have these closed for cosmesis.

Case 2

CC: Head laceration

HPI: 20 yo wrestler presents with a 4cm laceration to the top of the head. It happened 10 minute ago during practice when he took a knee to the area. His tetanus status is up to date and the laceration goes into the subcutaneous fat only.

Question

1) What are steps to repairing this wound?

Answer

1) Provide patient comfort, anesthetize and inspect the wound, clean the wound in sterile fashion, suture and provide patient follow up information.

Case 3

CC: Laceration to lip

HPI: 18 yo wrestler split his lower lip open during practice 30 minutes ago. Both the inside and outside lip is involved.

Question

1) Besides the standard procedures discussed above, what else should you consider with this wound?

Answer

1) Lip lacerations can be closed most of the time, as long the vermillion border is not involved. In this case it is close, but is not involved. Outer lip lacerations should almost always be repaired. Inner lacerations only need to be sutured in the case of very large wounds. Intra oral sutures are very irritating and unnecessary for small wounds. Use small absorbable sutures on the inner lip surface.

Case 4

CC: Hand laceration

HPI: 54 yo carpenter presents to the clinic one hour after sustaining a chainsaw injury to the right hand. Your exam reveals no foreign bodies. He has trouble extending the third finger.

Question

1) What is the prudent course of action here?

Answer

1) A surgical consult is warranted here because of the suspicion of a tendon injury. You can still check tetanus status, anesthetize the wound and properly clean the wound.

Copious irrigation with chainsaw injuries is important because of the oil and machine

lubrication used on this equipment. Leaving these sorts of chemicals inside a wound can contribute to infection and poor wound healing.

Case 5

CC: Scalp laceration

HPI: 60 yo farmer presents after a fall down stairs one hour ago. His head struck a manure spreader in his cow barn. He has not seen a doctor in over 20 years. The wound has extensive dirty material in it.

Question

1) What is you course of action in this case?

Answer

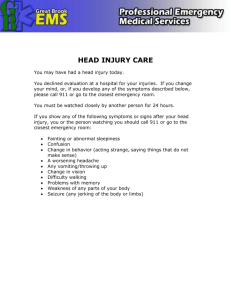

1) A history and physical will always help you. First, provide patient comfort and inform him of what you need to do. Next - why did he fall? Does he have any concerning neurological signs or symptoms such as nausea, radiculopathy, vision change or signs of a concussion? Remember you are responsible for treating the whole patient,

not just the laceration. If you are suspicious about intracranial pathology then obtain a noncontrast CT scan of the head to evaluate for subdural hemorrhages

Case 6

CC: Painful incision site

HPI: 62 yo man presents to clinic six days after gastric bypass surgery complaining that his incision hurts. He had a temperature of 100.6F overnight. Nothing is draining from the wound.

Question

1) What should you do?

Answer

1) Obtain a history and physical to start. The redness you see in the photo can be from a number of things. With a fresh postoperative incision you always need to have infection on your differential diagnosis. The fever of 100.6F can be from an infected site, but in his case could also be from postoperative atelectasis, a much less concerning entity. If any drainage accompanies the redness it would make sense to start him on appropriate antibiotics to cover for common skin microorganisms.

References

1) Smith DW, Peterson, MR, DeBerard SC. Local anesthesia; Topical application, local infiltration, and field block Postgraduate Medicine, vol 106, no 2, August 1999.

2) http://www.studentbmj.com/issues/03/05/education/140.php