Question 1

advertisement

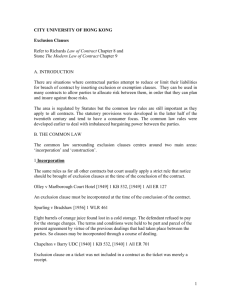

LAW EXTENSION COMMITTEE WINTER SESSION 2008 CONTRACTS ASSIGNMENT 2 GENERAL COMMENTS Question 1 This question raised two major issues. First, there was the question of whether the exclusion clauses formed part of the contract. Given that a contract was signed, the signature rule, as set out in Toll v Alphapharm, needed to be discussed. Most students did so and many concluded that the clauses had been incorporated into the contract. On the issue of incorporation, the facts of the problem were very similar to those in Toll. However, better answers raised the distinction as to whether the absence, on the facts of the problem, of a clause on the front page referring to the presence of writing on the back page, meant that the signature rule did not apply to the exclusion clauses. Could it be argued that the signature only covered the terms set out on the front page, and because there was no reference on the front page to terms on the back page, the exclusion clauses were not covered by the signature rule. If this was the case then reasonable notice rules would have to be applied to see whether the exclusion clauses were incorporated. Cases such as Thornton, Curtis, Parker and Causer v Browne are key cases on notice in relation to unsigned documents. A number of students mistakenly asserted that notice was necessary in relation to the signature rule. This was rejected by the High Court in Toll. A few students did not deal with this issue at all. The second key issue arose if the exclusion clauses were part of the contract. It was whether they excluded Ground Force for liability to Harvey. This raised the issue of contruction of exclusion clauses, in particular, in relation to clauses excluding liability for negligence. The general principles of construction of exclusion clauses, set out in Darlington Futures v Delco, needed to be set out before dealing with more particular principles in relation to exclusion clauses and negligence, as set out in Canada SS v R, and in particular whether the third rule in the latter case still applies in the light of the decision in Darlington Futures. If it does then, assuming that there is concurrent liability for breach of contract as well as in the tort of negligence, Ground Force would not be protected from liability in negligence. However, if rule 3 no longer applies, the exclusion clauses on their normal ordinary meaning would probably protect Ground Force from liability in negligence, as well as contract. Not all students adequately addressed the Canada SS principles, especially the applicability of rule 3. A number of students discussed statutory provisions. These were irrelevant as the question specifically asked that the discussion be confined to common law principles. Question 2 This question raised the issue of the meaning of performance of contractual obligations. To recover the contract price or part of it, a party must have performed. Common law requires strict performance which clearly has not occurred here. This being an entire contract, there was no right to recover payment of the contract price. The principle of substantial performance clearly could not apply in a situation where 40% of the work had not been done. Cases such as Cutter v Powell were illustrative. The alternative scenario raised the question whether there was a divisible contract, which would allow for payment of each part of the contract performed. As three rooms had been done, Joe would be entitled to recover the $2,400, as he has clearly performed the carpeting for each of the 3 rooms. A number of students argued that there was frustration. The fact that Joe’s supplier refused to supply him with further carpet is not a frustrating event.