Tropical Cyclones, the MJO, and El Nino

advertisement

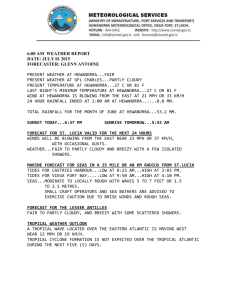

Friday Weather Discussion – 13 March 2015 The focus of this discussion is on recent developments in the tropical Indian and Pacific Oceans as well as their possible multi-scale, multi-basin impacts. Introduction There are currently four tropical cyclones extending from the west coast of Australia to the westcentral Pacific: Olwyn (western Australia), Nathan (eastern Australia), Bavi (Northern Hemisphere), and Pam (Southern Hemisphere). Of these, Pam is the most intense. Olwyn is of typhoon/hurricane intensity, while Nathan and Bavi are of moderate tropical storm intensity. Current visualization of GFS-derived 1000 hPa streamlines and wind speed o Note the twin cyclones, Bavi and Pam, with cross-equatorial flow between them and a col region along the equator. The cross-equatorial flow from the Northern to the Southern Hemisphere also feeds into Nathan, south of Papua New Guinea and east of Australia. Current visualization of GFS-derived 250 hPa streamlines and wind speed o Note the well-defined poleward outflow channel to the east of Pam. Bavi is embedded within relatively fast easterly flow aloft; not coincidentally, it is expected to move fairly quickly to the west (fast steering) with little change in strength (moderate shear) over the next several days. Divergent flow is noted aloft of Nathan, while Olwyn is becoming embedded within the mid-latitude flow. Wide-Area Infrared Satellite Loop Storm-Specific Charts (click on each storm’s icon on the map) o Focus on track and intensity forecast information, infared satellite, 85 GHz microwave imagery, satellite-derived deep-layer vertical shear, and satellitederived mean steering flow (DLM). MIMIC total precipitable water, sea surface temperature, and ADT intensity analyses are also of note for each storm. Model Guidance and Microwave Satellite Loops o Focus on the late cycle track and intensity guidance as well as the CIRA AMSU 89GHz imagery available for each storm. Of particular note amongst the above storms are Olwyn, which is skirting the western coast of Australia, and Pam, which is one of the most intense tropical cyclones on record for the Southwestern Pacific Ocean. Focus on Olwyn… o Storm surge charts from Australia’s Dept. of Transport: Note residuals of ~1 m from Exmouth down to Carnarvon along the northwest coast of Australia over the most recent day or so. o Carnarvon wind profiler data (courtesy Sarah Fitton, BoM): Note decidedly warm-core structure, with peak winds of ~100 kt around 850 hPa, just above the boundary layer, and relatively weak winds aloft, including reduced winds as the cyclone has its closest approach. o Guardian report on Olwyn’s impacts o Forecast and societal challenge: track of cyclone parallel to the coastline. Olwyn was forecast to track just inland but has instead remained just offshore, enabling it to maintain its intensity – or, late on the 12th and early on 13th, actually intensify – as it tracks southward. Archived track plots help to tell this story. Hurricane Charley from 2004 is a recent Atlantic analog to this. How to best communicate uncertainty to decision-makers? What level of forecast accuracy should we expect? How should – and do – people respond in such scenarios? Focus on Pam… o Forecast and societal challenge: track of cyclone parallel to island chain. Pam is currently tracking along and across the island nation of Vanatu and is currently very close to Port Vila (pop: 44,040), the largest city of Vanatu. The official report from the Vanatu Meteorological Services has the center 45 km east of Port Vila, placing Port Vila just outside the eyewall – albeit fortunately on its west side, where the direction of storm motion is opposite to that of cyclonic flow. Societal impacts are briefly discussed in this CNN report. Minimum pressure recorded at Port Vila was 942 hPa with winds gusting to 60 MPH; estimated minimum central pressure of Pam was 899 hPa. How to best prepare those on an island nation, often with poor construction, for a nearly-unprecedented impact, particularly one where a small track shift could drastically change the impact? o Scientific challenge: numerical model representation of tropical cyclones. Given improvements to data assimilation methods and model resolution, among other elements, many global models are now capable of simulating realistic intense tropical cyclones. See also recent ECMWF and GFS forecasts, noting that both are too weak at initialization (now) and are substantially different (ECMWF more intense than GFS) at later times. Are these forecasts realistic? Dubious, perhaps, given uncertainties regarding methods of tropical cyclone intensity change and the lack of data from within the inner core of such cyclones. What are the biases of such forecasts, both with respect to intensity and production/genesis? What is needed to realize further advances in intensity prediction, the skill of which has generally not changed over the past 10+ years? Ocean model coupling? Inner core data? Improvements to model physics? What role does limited-area, higher-resolution deterministic guidance play moving forward if global models – which are generally pretty skillful with respect to track – become competitive on intensity? Do we move to ensembles? o Downstream/Mid-Latitude Impact: note forecast interaction of Pam with a downstream jet streak. Strong divergent (irrotational) flow aloft intensifies this jet as it amplifies the downstream ridge, after which time a cyclonic wave break occurs downstream in the forecast. Cyclogenesis that occurs in response to the amplified trough leads to an amplified ridge downstream, followed by an amplified trough that undergoes anticyclonic wave breaking west of South America. Of course, all of this is in a single model forecast (from the 0600 UTC 13 March 2015 GFS), and this can and likely will change moving forward. There is minimal societal impact no matter what verifies, however, given the lack of population in the Southern Hemisphere mid-latitudes. Twin Tropical Cyclones and Equatorial Rossby Waves Pam and Bavi are twin tropical cyclones that formed in association with the cyclonic portion of an equatorial Rossby wave. 5-13 March 2015 TRMM-derived precipitation rate and GFS-derived 850 hPa wind Equatorial Rossby wave monitoring and forecasting o Derived from filtered OLR anomalies, filtered with respect to wavenumber (zonal extent and direction of motion) and frequency (recurrence). ERW, MJO, and Kelvin wave monitoring and forecasting o Note other cyclonic equatorial Rossby wave events in early January and early February. There were western North Pacific tropical cyclones at about these times (Mekkhala, Higos), as well as a western South Pacific tropical cyclone (Ola) in February, each at about the longitude of the identified ERW feature. Not all ERWs result in tropical cyclones, let alone twin cyclones, however. Equatorial Rossby waves are one possible solution to the shallow water equations (for equatorially-trapped wave modes). Convective heating, such as associated with latent heat release in areas of convection, is one means by which an equatorial Rossby wave can be triggered. Our nine-day loop above does not go back far enough to allow us to identify the formation of this ERW, but we can infer near-equatorial convection prior to the genesis of Pam and Bavi from the TRMM-derived rainfall rate field. Other Modes of Tropical Variability Our four tropical cyclones appear to have formed in conjunction with an active MJO event, as can be inferred from the ERW, MJO, and Kelvin wave monitoring and forecasting link above. Current MJO phase diagram: Note the high amplitude in phase 6, with sqrt(RMM1^2+RMM2^2) of approximately three as of 12 March. Though the MJO phase diagram primarily varies on the time scale of the MJO, intense synoptic-scale perturbations (such as tropical cyclones) can project onto it. Feb-Mar-Apr MJO phase-based composites of 850 hPa wind and OLR anomalies: Phases 5 and 6 are nearly dead ringers for the full 850 hPa wind and TRMM-derived rainfall rate charts referenced above. The preferential formation of tropical cyclones during active MJO phases across the basin is well-known; how the MJO forms, however, is not. Note the anomalous westerly flow along the equator in these phases; we’ll return to this shortly. Dynamical model MJO forecasts: Even as Pam moves into the mid-latitudes and Bavi moves westward, the active MJO event is widely predicted to continue to amplify over the next 3-5 days. A peak forecast amplitude of > 4 in phase 7 would be the highest recorded since 1974 (the period of record). The current record is 3.85, set in mid-March 1997, preceding a strong El Nino event. The two strongest MJO events, by amplitude (~4), on record occurred in February 1985 (phases 4-5) and March 1988 (phase 4). A Developing El Nino? Depending on the metric considered, the equatorial Pacific has been in an El Nino state for the past year or so. Generally, this has been a “west-based” El Nino, with the greatest warm anomalies found in the central Pacific rather than the eastern Pacific. Further, the greatest warm anomalies have been found in the sub-surface, with a lowered thermocline, rather than at the surface. Current and recent SST/SST’ and sub-surface T/T’ 90-day 850 hPa equatorial zonal wind, anomaly; 30-day+forecast 850 hPa equatorial zonal wind, anomaly: Note the current and forecast strong westerly wind event occurring just west of the International Date Line, in conjunction with Pam/Bavi and the MJO event. We’ve also seen strong easterlies in the equatorial eastern Pacific, with the upwelling that accompanies them likely keeping SST in check there. This is forecast to end, however, in the coming days. IRI ENSO Forecast: weak to moderate El Nino event predicted by a consensus of dynamical and statistical models, although we are near the spring “predictability barrier” (ENSO phase predictions during spring exhibit reduced skill compared to those at other times for unknown reasons; this presents a notable scientific opportunity, too!). We can see this from the CFSv2 forecast plumes from early March and the ECMWF forecast plumes from February. ENSO Composites (2-m T, precipitation): another below-normal summer in store? Note that there is substantial variability from one El Nino or La Nina event to the next; that an El Nino event by no means precludes there from being periods of warmth; and that conditions may be quite variable near the lakeshore until the lake warms.