THE SOCIO-LINGUISTIC HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE

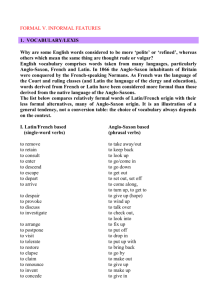

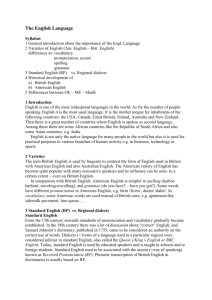

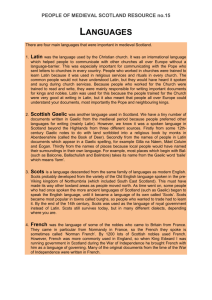

advertisement