Peat Stratigraphy and Long-Term Succession of Bayhead Tree

advertisement

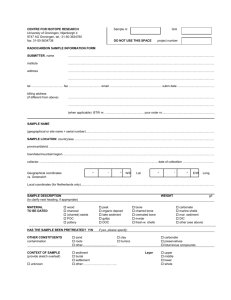

Peat Stratigraphy and Long-Term Succession of Bayhead Tree-Islands in the Northeastern Everglades Peter A. Stone SC Dept. Health and Environmental Control, Columbia, SC Patrick J. Gleason Camp Dresser & McKee, Inc., West Palm Beach, FL Gail L. Chmura McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Tree-islands are distinct patches of forest surrounded by low-stature vegetation. Though common worldwide, tree-islands in the Everglades are among the best known. The northeastern Everglades hosts one of the main vast assemblages, though it is now substantially diminished. Nearly all that remain are in the A.R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge (CA1) where they are a dominant landscape feature. Others, formerly extant in Conservation Area 2A (CA2A), are now destroyed, mainly by impounded flooding. Here, we deal with those found on relatively thick peat that seem unrelated to any local surface features on the buried mineral substrate. These include seemingly all those in Loxahatchee NWR and most those formerly in CA2A. (In CA2B and possibly southernmost CA2A, the mineral-mound-focused tree-island predominated, similar to most tree-islands in the middle and southern Everglades, excluding mainly the so-called SE “saline” Everglades.) This northeastern portion of the Everglades is characterized by an abundance of marshes dominated or codominated by waterlilys, i.e., deeper marshes. Waterlilyrich peats in profiles below the marshes attest to the long prevalence of this general conditionsince the Everglades peatland began, almost 5000 14C years in the oldest areas. Sawgrass too is and has been common, occurring now in large elongated strands down to small patches. Small patches of other shallower-marsh marsh plants are common as well. Two main types of tree-island occur(red): (1) roughly 100 large (to 1.5+ km long) elongated (“cigar” shaped in map outline) forests principally of dahoon holly occupying low, seasonally flooded, peat ridges, and (2) thousands of small (to a few 10s of meters in diameter) more-rounded clumps of trees with redbay usually codominant, on distinct mounds of peat (ca. 1 meter high in surveyed examples). Complete peat profiles obtained by coring were examined for peat-type stratigraphy (main parent plant, shown anatomically in microscope thin section) and for pollen stratigraphy. Pollen and several peat profiles are newly presented here. All nine tree-islands (5 large, 4 small) had forest peat only as an uppermost layer, with marsh peats below. All had initiated upon marsh surfaces somehow, after 3000+ 14C years of marsh existence at their sites. Most showed a stage of emergent marsh at their sites between the era of waterlily prominence and the formation of the eventual tree-island. Sawgrass was most common as this intermediate, but arrowhead occurred prior to two tree-islands (1 large, 1 small). At the sites of present large tree-islands, spores (in the pollen analysis) show that the later marsh stages were rich in ferns, which if they represent growth at the immediate sites suggest shallower examples of sawgrass marsh (the sawgrass shown by peat type). Waxmyrtle first prevailed as a woody colonist, only later surpassed by the dahoon holly. It seems quite likely that the large tree-islands colonized large individual sawgrass strands already growing on low ridges, whereby the shaping and elongation occurred mainly in a previous stage. Some distinct sawgrass strands in the western fringe area closely resemble the treeislands in size and outline. Either a shift to a less-wet condition (say, climatically controlled) or a relative rise in local elevation (presumably by faster peat accretion in the sawgrass strands) or even plausibly just a reduction in fire frequency may have induced the replacement of sawgrass by bushes and then trees. Curiously, one site showed a much earlier trend to woody vegetation (by presence of waxmyrtle pollen), but this later reverted back to marsh dominance before finally succeeding to a tree-island. Most small tree-islands showed an intermediate stage of emergent marsh peat (sawgrass or arrowhead). But one may have formed directly upon waterlily marsh peat. Colonization of a floating peat island is a way this could have been accomplished, but resinking of such peat mats very possibly explains the origin of the more common shallow marsh stages of the other small tree-islands as well. Pollen stratigraphy of one small tree-island showed a prominence first of waterlily, then of arrowhead, then ferns, then waxmyrtle, then holly. It is difficult to say whether the arrowhead and ferns were themselves instrumental or even diagnostic of conditions instrumental to the later transition to bushes and forest here. The peak of arrowhead pollen lay substantially below the beginnings of waxmyrtle importance (ca. 230 cm vs ca. 170 cm, in a ca. 320 cm deep peat profile). A small peak of buttonbush pollen at ca. 155 cm depth, the same depth as the onset of holly pollen, may be significant. Buttonbush is a common colonist on new floating peat islands. The small tree-island is apparently the older type. To 1.5 meter thickness of forest peat occurs, with several dated basal peats ranging roughly 8001300 14C years old. Only thin forest peat is found in the large low tree-islands (ca. ¼ m), too thin to reliably date by 14C methods (another dating method should be undertaken). Peter Stone, Bureau of Water, SC Dept. Health and Environmental Control, Columbia, SC 29201 Phone: 803-898-4151, Fax: 803-898-2893, stonepa@dhec.sc.gov