A Qualitative Investigation of Academic Resiliency in Hispanic

advertisement

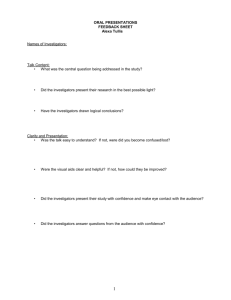

A Qualitative Investigation of Academic Resiliency in Hispanic Family and Consumer Sciences College Students: “On Saturdays, my dad would take us to the onion and chili fields and show us what work was like if you don’t go to school; it was in my childhood that I knew I would go to college.” Jennifer L. Gilliard, Ph.D., L.C.P.C. The University of Montana Western Sharon Jeffcoat Bartley, Ph.D. New Mexico State University sbartley@nmsu.edu Project Summary In 2010, Hispanics in the United States composed 16% of the total population, totaling 50.5 million people (Humes, Jones, & Ramirez, 2011). Projections suggest that Hispanics will comprise approximately one-third of the total U.S. population by 2060. However, over 90% of the American teaching force is European-American (Nieto, 2000) and largely unprepared to educate a growing population of linguistically and culturally diverse learners (Nieto, 2002). How are Hispanic learners impacted by an educational system that predominantly reflects European-American culture? The dropout rate of Hispanics is the highest of all minorities, with approximately 30% leaving high school before graduation (Moule, 2012). This project investigated academic resiliency in Hispanic college students and was framed around the following question: what factors support academic resiliency in this population? The researchers hoped to gather information to better equip the American teaching force to meet the needs of Hispanic learners during elementary and secondary education, by facilitating academic success and preparation for college in this population. Two focus groups lasting approximately one and a half hours each were conducted by the researchers; participants were 10 Hispanic female college students, enrolled in family and consumer sciences majors. Researchers asked the participants a series of prepared questions centered on the research question. The researchers tape recorded the focus group sessions and took notes. Participants were asked to take turns answering the questions and were at times asked follow-up questions. Data included the researchers’ notes and transcriptions of the audio tapes. The investigators sorted data by color-coding pertinent responses from the data consisting of the transcribed interviews and the researchers’ notes. Investigators compared color-coded data for accuracy, discussing any variations or discrepancies. Data were studied an additional time, and investigators identified and clarified themes within the research question. Themes were defined by noting whether at least eight responses from the data sources supported the main concept of the theme (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Finally, data were re1 read by investigators marking agreed-upon categorization changes as needed. Data analyses revealed three themes focusing the research question: 1) different ways that the family of origin influences education; 2) school and peer influences; and 3) personal resources and situations. Findings suggested that the following could be supportive of academic success and college admission of Hispanic students: encouraging and establishing an avenue for parental involvement in education; community programs that provide care for younger Hispanic children so older siblings can pursue their education; after-school programs that provide academic tutoring and child care; frequent academic goal setting and planning sessions; peer support groups; and academic and life skills counseling. Rationale for the Study Given the high dropout rate of Hispanic high school students as stated in the project summary, the investigators were interested in learning more about the factors that support academic resilience in Hispanic college students. Based on project findings, the investigators hoped to contribute suggestions for supporting academic resilience and success in Hispanic elementary, high school, and college students. Participants and Setting The participants of the study were 10 female Hispanic Family and Consumer Sciences college students from a department of Family and Consumer Sciences in a land-grant, Hispanic-serving university located in the southwestern part of the United States. Research Question, Data Sources and Procedures The research was guided by the following question: what are the factors that supported academic resiliency in this population? Data were collected over two days and included 1) responses from two focus groups each with five participants, and 2) field notes from the two principal investigators. Focus group discussions were taperecorded. Socio-demographic data were collected using a survey that was distributed immediately before the focus groups began. Participants also signed informed consent forms at this time. Subjects were self-selected and responded to flyers posted within their academic department along with announcements made in their courses. Focus groups lasted approximately 1 ½ hours and participants responded to questions that were predetermined by the investigators. Because the investigators were European-American and not Hispanic, they opted to arrange or seat the focus group participants in small circles with the investigators sitting outside of the circles. The investigators did not want to hinder the groups’ discussions that related to cultural understandings outside of the researchers’ personal cultures. The investigators introduced the study to participants including purpose of the study, procedures, voluntary participation, and confidentiality before subjects responded to questions. Investigators sat outside of the participants’ circle adding clarifying questions and reflections as deemed necessary. The investigators summarized participants’ responses and answered questions at the end of the focus groups. 2 Data Analysis The investigators independently sorted the data by color-coding pertinent responses to the research question. Coded data were compared for accuracy, with investigators discussing variations. Data were read again for the purpose of creating clarifying themes within the research question. Themes were determined by noting if at least eight responses from the two data sources alluded to the main concept of the theme (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). After that, investigators re-read the data noting categorization changes as needed. Followed by discussion of meaning, minimal modifications were made involving interpretation of responses. Results of the Study The results of the study were grouped according to the research question: what are the factors that supported academic resiliency in this population? They are examined through themes that consistently emerged under the question. The themes focusing this question were: 1) family influence; 2) peer and school influences; and 3) participants’ personal resources and situations. Distinct categories emerged within each theme. Four categories emerged within the family influence theme: parental attitudes toward education, financial status of the family of origin, sibling order and sibling support, and education level of the parents. Categories that emerged under peer and school influence included peers’ knowledge of education, peers’ academic resiliency, and special school programs targeted at academic success along with quality experiences with school guidance counselors and teachers. Last, two categories emerged from the theme of participants’ personal resources and situations. These included participants’ determination to succeed, and life circumstances that included pregnancies and marriages. Some of the data that shaped themes were based the following participant responses: Family Influence The most important thing in my family was to get married and not be a burden to my family. I was looking for someone to marry, that was my goal and eventually I did. Elementary was hard for me because my mom was a single parent and she worked. She would come home tired and my grandmother didn’t know any English at all so she couldn’t help me. Her education was very limited; she only made it to second grade in Mexico. Because she (mom) was the oldest, she had to stay home and take care of my aunts and uncles because they (grandparents) would work in the field. Mom’s education took a backseat to taking care of her siblings. My brothers and sisters all pulled their money together and paid for my dorm room my first year of college because at home, everything was all up and down. My dad said, “I came to the United States so you guys could learn English and get a better education.” He is real big on education. 3 Peer and School Influence When I did start elementary and kindergarten, my teacher let me stay for both AM and PM sessions because she didn’t want me to go out into the fields or be alone. When I was in high school I had a group of friends that were really into school so that helped me out. I did stay in college prep classes. The class was AVID, Advanced Via Individual Placement. It helped me a lot when it came to getting into college. My guidance counselor was available to me but I think it was just listening to my Caucasian friends talking about going to my guidance counselor because they had to sign up for the ACT. That is how I got my information. From that moment on, I had the push from my counselors; they would walk me to class and say you need to come and apply for this right now. M y teachers were looking out for my well-being. That and my family is how I got where I am today. The people I hung out with were people who didn’t do their homework. I hung out with them because I felt comfortable with them. I found a lot of similarities with those families so I would hang out with them because they were just like me and my family--barely making it, only had one car, we didn’t have the great things that my other friends had. Participants’ Personal Resources and Situations College was my number one priority. School has always been my number one priority. I don’t want to end up like in a statistic that said, she’s Hispanic, she is dropping out. The only thing (barrier to education) I could think of would probably be getting pregnant in high school. My parents told me they were disappointed. The main reason I want to finish college is because I want my parents to be proud of me and I want to show them that all they did wasn’t in vain. Implications of the Study Findings suggested that the following could be supportive of academic success and college admission of Hispanic students: encouraging and establishing an avenue for parental involvement in education; community programs that provide care for younger Hispanic children so older siblings can pursue their education; after school programs that provide academic tutoring and child care; frequent academic goal setting and planning sessions; peer support groups; and academic and life skills counseling. 4