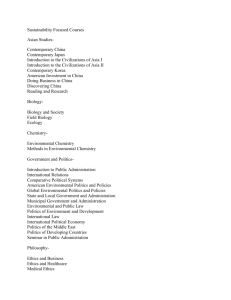

Power and Political Institutions

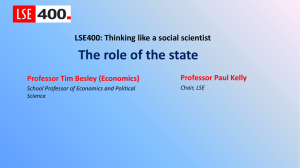

advertisement