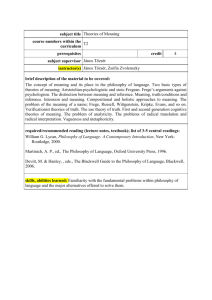

Theories of Mental Representations

advertisement

The development of this course has been funded by the Curriculum Resource Center (“CRC”) at the Central European University (“CEU”), whose programs are partially funded by the Higher Education Support Program (“HESP”). The opinions expressed herein are the author’s own and do not necessarily express the views of CEU. Lecturer: Host Institution: Course Title: Year of CDC Grant: Juraj Hvorecky Charles University Theories of Mental Representations 2002 / 2003 Introduction The course “Theories of Mental Representations” (TMR) was taught at the Institute of Philosophy at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University during the spring term of 2003. The course was designed as an advanced elective course for students in the second half of their studies (3rd, 4th and 5th year). TMR aimed at giving students an option to indulge into present-day analytic thinking over the topic that unites philosophy of language, logic and mind. My aim was to present students with recent developments in an attempt to integrate traditional puzzles in the theories of meaning within the context of philosophy of mind and philosophically minded cognitive science. Debates over the nature of intentionality, together with a time spent on integration of semantic issues and their internal implementation, dominated the course structure. Given a prevailing tradition in Prague’s philosophy, TMR offered students a unique opportunity to experience contemporary Anglo-Saxon philosophical culture. There is no course that would go through a remotely related literature. Although students are familiar with the basics of analytic philosophy, and rudimentary theories of meaning are offered during logic classes, full-fledged theories of representation were never delivered. TMR was of a great benefit to advanced graduate students interested in contemporary literature to confront their knowledge with their likeminded fellows. Prerequisites for the TMR course included both philosophical and language skills. On the one hand, participants were expected to have some basic training in analytic philosophy, some acquaintance with the terminology used and knowledge of basic philosophical strategies, peculiar to contemporary Anglo-Saxon thinking. On the other hand, fluency of reading in English was presupposed. As virtually all study material was in English, fairly high linguistic constraints were placed on each student. Objectives of the course To demonstrate the current state of the field that unites philosophy of language with philosophy of mind. Discussed are the constraints any theory of meaning should implement should it account for naturalistic tendencies within a philosophy of mind. Given the vast experimental and conceptual advances in the field of cognition, debates over the nature of concepts, reference or intentionality cannot be held without some account of how all these features of language/thinking are implemented. The course sets to debate the issue of evaluation of several popular theories of meaning through the lenses of subjective mental limitations. Constraints of computational power, finite resources and compositionality lead us to abandon several widely held assumptions about mental representations. Various forms of holism will be reconstructed in several different semantic proposals and their relevance considered. Atomistic conceptual content will be demonstrated to offer better basis for content naturalization. During the course, students will have a first-hand approach to literature, master both pro and con arguments in several competing theories of representation and develop their argumentative skills. Because of the difficulty with the language of primary resources, indirect improvements in their linguistic capabilities should be observed. Emphasis is put upon the careful attention of argument developments. Lectures are held in such a way that consecutive meetings respond to supposedly strong conclusions from previous sessions and the strength of new premises is judged. Overriding principles of taking seriously cognitive constraints are observed. Given the interdisciplinary nature of some of the classes, stimuli from cognitive science for philosophy will be measured and a framework in related sciences considered. Because of familiarization with the topic, at least two students decided to pursue related topics for their diploma works. III Course Details Lecture 1. A shorter session without a seminar. Apart from a distribution of syllabus, relevant information about the course is spread around. The general direction of the class is outlined, presentations and commentaries are distributed. Information about readers and their location is made public. The educational and linguistic background of students is briefly reviewed and information about student’s assessment is discussed. Lecture 2. Basic notions of theories of meaning are introduced. Brief history of the modern logic and philosophy of language is outlined, with emphasis on Frege and Russell. Students familiarize themselves with the distinction between sense, reference and a mode of presentation. Non-mental theories of meaning and their recent developments are presented. A possible role for the mental is played out and the Gricean program of meaning as interpretation is sketched. It is shown that Gricean models do not go far enough in assessing the role of psychology in meaning transfer. Seminar/Tutorial Synopsis Lecture 3. The field for mental representation is being introduced, but a serious philosophical counter attack against any construction of internal meaning has first to be rebutted. In this class we deal with the challenge of externalism and review well known arguments in its support. Putnam’s Twin Earth is presented and issues concerning the meaning of natural kind terms debated. The argument is then extended with Burge’s claim about social nature of all terms. Causal theories, as the most usual forms of externalism are briefly introduced. The session concludes with the claim that it might look like an externalist argument makes any talk of theories of mental representation impossible. Lecture 4. After a brief reminder of externalist strategies, internalism is presented and together with it the very possibility of mental representations defended. Fodor’s argument about psychological realism that forces one to take seriously mental constraints on the theories of meaning is developed. The subjective domain of inner manipulation with contentful states, together with counterarguments against externalism is described. In sidestepping, counterfactual exposition of causality is explained and the relation of content to world is reaffirmed. Lecture 5. After seeing that externalism is not the only game in town, we will follow the exchange on the topic a bit further. The second round of the debate is played out, this time taking into consideration a broader philosophical background of possible worlds and theories of perception. Fodor’s newer argument and his slow recession from strong internalist positions are tracked, together with a demise of narrow/wide content debate. Searle’s internalist arguments and their self-referential structure adds support for internalist theory, but some externalist critique of his position is also introduced. An area for internalist is finally demarcated and opened for closer looks at the constitution of mental representations. Lecture 6. First internalist theory is evaluated. Mental representation according to functional role semantics consists of functional roles that such a content plays in our mental lives. Notions of philosophical functionalism are first introduced and causal roles and ramsification are explained. We demonstrate how functionalism is implemented to content theories. Position of an inference as a crucial internalist clue to content goes under scrutiny. Some psychological evidence is brought up to back the claim of a functionalist. Issues of truth conditions and irrelevance of the outside world are presented. Revised Cartesian picture is offered and the possibility of a neural plausibility of the functional role semantics is deliberated. Lecture 7. Reviewing internalist strategies of functional role semantics with the stress on implementation problems and introduction of its holistic consequences. How can a good proposal of constituting features of representations be brought forward in times of the demise of analyticity and definitions? Fodorian worries about holism are exposed and his atomistic proposal taken seriously. Language of Thought as the most promising contender for a TMR is shown as satisfying all semantic and syntactic requirements. Interplay between syntactic bearers of meaning in the brain and their semantic evaluation is depicted in detail and so is the atomistic informational intuition that opens the road for mental representations as such. Lecture 8. Once the schema is designed that can host internal mental representations that both fits syntactic processes in the brain and semantic evaluation, the question of the very nature of semanticity is raised. How can anything in nature bear intentional properties? Few naturalistic replies are introduced. Starting with suggestions of natural representations that do not necessitate the interpreter we are talking about Fodor’s asymmetric dependency idea and Millikan’s biosemantics. A causal story with co-variance as a basis for intentionality is taken seriously and the two players are judged accordingly. Differences in their conclusion about intentionality of lower animal’s acts are elaborated. Lecture 9. As any other philosophical project, naturalization of content has its contestants. We will look closely at the most famous of them, the Swampman. On the background of the lecture, there is an important question about how to construe arguments in general: is it fair to use non-naturalistic arguments of a conceivability kind against naturalistic premises? It doesn’t seem particularly relevant to claim the nomological laws do not hold because there are metaphysical considerations they do not take into account. Recent thoughts by Papineau on the same subject are reviewed and a dichotomy of naturalism vs. conceivability is defended. Preliminary closing remarks on a philosophical part of the course are made and a transition to empirically guided considerations is carried out. Lecture 10. With this lecture a brief empirical part of the course begins and we will show how experimental findings disprove particular ideas about concepts and mental representations. We are going to see a standard theory of prototypes and stereotypes, as well as cognitive models of concept acquisition in various domains. Prototypes will be shown in some details as they are both influential and entertaining. Their importance lies in the fact that despite showing something important about the psychology of concepts, the outcome of the theory is very partial. Issues of compositionality are one such example to be discussed. Later developments with feature lists, stereotypes and weighted measures are also to be included. Another psychological input comes from innateness hypotheses and developmental literature. Nativist arguments about a variety of primitive concepts are lectured upon. Lecture 11. Experimental data presented during the previous lecture are freed from their interpretative theory and taken at a face value. Competing accounts of the same data are introduced. Lakoff and his cognitive semantics, that widely employs a notion of metaphor is favorably offered a viable alternative. Lakoff’s broader conceptions of language as an expressive embodiment is explained and his story of concepts as cognitive models that retain one meaning in seemingly disparate conditions is supported. What Lakoff says is paralleled by in philosophy by conception of nonconceptual content. On a side, Peacocke writing on non-conceptual content is presented and some take-home messages, related to previous philosophical debates, are drawn. A possible relation between embodiment of Lakoff’s type and nonconceptual content that goes beyond our conceptual capacities is suggested. Lecture 12. Inputs from another branch of cognitive science, artificial intelligence, are taken into account. Basics of computational paradigm are developed, Turing machine as a model of mind is briefly presented and classical AI architecture is shown. A contrast with neural networks is made. Computation without an explicit representational structure is outlined and the notion of implicit representing is established. Philosophically significant judgments in connectionism are offered. Among them the primacy is given to both brain considerations that purport to give potency to the connectionism and to the idea of sub-semantic contents in nodes and connections. The latter is implied as a potential answer to various implementational troubles with competing architectural proposals (i.e.modularity). It might also hold an unexpected naturalistic answer to several worries TMR is facing (neural plausibility, throughout naturalism, a question of design). Lecture 13. Critical analysis of connectionism is reviewed and inability of connectionism to offer a real alternative to stronger representationalism is presented. Argument from systematicity, productivity and compositionality of language/thinking used against connectionist accounts of concept acquisition/possession. Failure to deal with what Fodor calls non-negotiable criteria on the theory of concepts is taken as a downfall of the entire connectionist project to account for workings of the mind. A significance of connectionism in computing is maintained, but it is stripped of any major role in philosophy. Some counterevidence against a univocal dismissal of connectionist models of mind is delivered, but its overall weaknesses in generality rule it out. Strong modularist thesis is advocated. Lecture 14. Closing lecture: we review the course, following shortly its path from the beginning to the end. Starting from a demarcation of the very sense of internal representations, we looked upon various theories of internal meaning bearing symbols, observed and compared their force. Seeing a holistic nature in most of them, we opted for an atomistic theory of mental representations. The second part of the course was an attempt to see whether empirical evidence can disapprove our preliminary philosophical conclusions. It turns out that developmental literature, research on forms of representations (prototypes etc.) and neoclassical psychological theories of concepts either do not refute conceptual atomism, or actually support it. The attack from connectionism is also found to be flawed and a strong representationalism is seen as the most promising TMR. Seminar 1 – no seminar Seminar 2 – Comparison and contrast between two early theories of meaning is portrayed. Emphasis is given on long and detailed exposition of Ryle that includes no mental categories, juxtapositioned next to Grice, who attempts to assign some role to the mental in meaning transfer. Behaviourism and mentalism of both players is reviewed and roles of these theories in general theories of meaning are discussed. Essential questions: How does Ryle view the history of philosophy of language and what dominant issues he sees as crucial? Does he use any mentalist vocabulary? Why? How does Grice enrich the debate? What role for the mental does he assign? Is such an assignment sufficient? Seminar 3 – Due to the length of Putnam’s seminal paper, shorter works of externalists Burge and McDowell are scheduled. The stress is put on Burge’s famous exposition of social nature of linguistic items. Problems of extending Burge’s argument to the entire lexicon is discussed. McDowell’s paper is supposed to show how the externalist debate overcomes the Cartesian heritage. Place of externalism in modern philosophy, seen through McDowell’s reading of Russell is opened for questions. Essential question: What does Burge’s argument show about the nature of our lexicon? Does the non-negotiable condition of sharing meaning inevitably lead to externalist conclusions? Is the only alternative left only Cartesian? What is McDowell’s message about the inner space of mind? Seminar 4 – Two counterattacks on works presented previous week are waged. First, Carruthers’ paper questions McDowell’s and other externalist readings of Russell, defending internalism against the charge of Cartesianism. Second, Fodor’s chapter from Psychosemantics shows how counterfactual arguments unveil weaknesses in conclusions of Putnam and Burge. Weight of internal manipulation with contents is debated and demonstrated on Fodor’s text. Essential questions: What does thinking about any object consists of? How can externalist deal with non-existent entities? Why having externalist intuitions isn’t enough to refute the mind as a seat of meaning? Who is more faithful to Russell, McDowell or Carruthers? Seminar 5 – Modal arguments in support of narrow content of thoughts is put forward, together with some basic assumption of counterfactual reasoning in Fodor. Evolutionary arguments of his are put aside for further evaluation later. Burge’s review of Searle’s Intentionality book is assessed and a surprising affinity that Burge acknowledges is discussed. Questions about metaphysical significance of internalist theories are on the order of the day. Sufficiency the internalism for a solid representationalism of the mental is examined. Essential questions: Is the newer argument from Fodor any stronger than his older thesis? What changes did you note? How fair is Burge’s exposition of Searle? Is there really so much affinity between the two? If so, isn’t the debate between externalism and internalism purely verbal? Seminar 6 – Functional role semantics is presented and its ability to deal with various charges judged. Its position in respect to externalist views, concept acquisition and truth conditions are critically viewed. Fregean notion of ‘sense determining reference’ is especially scrutinized as doubts are raised about the ‘realist’ part of the functionalist picture. Queries on semantic evaluation of functional roles are put forward and possible strategies to fix the reference are determined. Chances to amend the theory with wide functionalism are evaluated. Essential questions: Can internal meaning be the functional role of a concept? What fixes a referent of a functionally described bearer of semantic properties? Do truth conditions present a problem for FRS, as Loar claims? Seminar 7 – The seminar looks upon the history and present state of definitional accounts of concepts. Analytic truth is debated and so is its collapse after Quine. The article of Fodor et al. illustrates this point very well: there is hardly any definitional content to any concept and the entire strategy of giving definition to even the most trivial examples from language/thought fails greatly. Students are asked to reconstruct historical empiricist attempts to come up with definitions and demonstrate their downfall. Positivist tradition is briefly sketched and Quine’s thoughts on the subject are reconstructed. Informational semantics is the suggested as a remedy for the misguided earlier accounts. The role of the informational account is surveyed throughout. Essential questions: Why is FRS holistic? What’s wrong with holism? How much does holism depend on definitions and a clear-cut distinction between analytic and synthetic judgments? In what respect does informational atomism escape these troubles? Seminar 8 – Causal theories of intentionality are the program for the day. Differences between Fodor’s counterfactual proposal and Millikan’s evolutionary account are sharply contrasted and the debate about a nature of evolutionary design is scheduled. We are after non-intentional circumstances that make some states intentional. While Fodor’s story is certainly philosophically relevant, Millikan has an advantage of being more easily implementable. Because both authors discuss the same ‘bug’ example, debate over distinctions between the two authors is importantly facilitated. Essential questions: What would one expect from a good naturalistic account of representations/intentionality? Does Fodor’s causal story lie at the bottom of the naturalization story? Can an evolutionary ‘design without a designer’ move the debate ahead? What is the strength, if any, of evolutionary arguments in philosophy in general? Seminar 9 – Though two papers are scheduled for this week, Davidson is given priority, because Stich simply describes nuances of the entire project of building a TMR. A significant portion of the seminar is devoted to a debate over Davidson’s thought experiment that is supposed to put the naturalistic/evolutionary story of intentionality into doubts. The idea of a Swampman and his derivations are carefully reconstructed and scrutinized. Davidsonian account of first person access to one’s own thoughts and his theory of subjectivity are also looked at. Because of its dependency on the entire structure of Davidsonian thinking, brief exposition to his notion of events and anomalous monism are necessary. Essential questions: What is Swampman and why should it trouble any devout naturalist? Could Davidson account for a privileged epistemic situation of the first person? What would knowing one’s own mind mean in this context? Is naturalism a philosophically innocent thesis, or is it in need of any further justification? What role do possibility arguments play in philosophy? Seminar 10 – Psychological texts are read for the first time and therefore some methodological issues, associated with the research in humanities, are first deliberated. Emphasis is given to the prototype studies of Rosch. Theoretical background and some practical outcomes of her experiments are presented. Limits of research are presented (odd numbers, verbs, compositionality of prototypes) and philosophical significance of findings assessed. Unanswered issues are reconstructed. Points about turning philosophy into full-fledged naturalism and psychology (‘epistemology naturalized’) are contested. Principles of Spelke’s and Carey’s long paper on concept acquisition are appraised. Essential questions: Could concepts be prototypes? What restrictions on a suitable theory of concepts prototypes do not fulfill? What positive results for a theory of concepts can one derive from Rosch’s research? Do Spelke and Carey have a strong case for nativism? Seminar 11 – More psychological and linguistic methodology is on the way. Lakoff’s example-rich article on cognitive models gives students a perfect opportunity to see working linguistics at its best. Cognitive unity beyond seemingly ambiguous words is discussed, though language limitations preclude students from fully enjoying his wellchosen vocabulary. Suitable alternatives in students’ native language are sought for. An exchange between Rey and Peacocke on concept individuation and non-conceptual content offers us a moment for speculations on the limits of concepts. Skeptical thoughts on how to specify non-conceptual content are voiced and challenged. Essential questions: Are Lakoff’s examples proving uniqueness of a concept? What is his argument against prototypes? What criteria does Peacocke offer for the individuation of concepts? Could you think of others? Is non-conceptual content a fruitful notion? Seminar 12 – Introductory readings from neural networks are the main topic for today. A longer explanation of what are nodes, weighted sums and neural computations is presented. Understanding Hebb’s law of strengthening of active connection and inhibition of inactive one is debated, using basic neuroscience data. A model of computing power and input/output relations is talked about and a necessity of invoking any notion of representation to explain them investigated. Transparencies are used to illustrate models of simple networks, backpropagation and recurrent loops. A theme of replacing rigid representations with statistical patterns is opened for a debate. Essential questions: Why are neural networks attractive to computer scientists? Should they be also attractive to philosophers? How to understand a replacement of complete representations with sub semantic elements? Could connectionism give a full picture of mind? Seminar 13 – Following the neural network literature from the week before, this week some essential methodological counterexamples are brought in to judge a strength of connectionist thesis about the mind. Productivity and systematicity arguments are debated; their counterparts in the native language of the course participants are used. Stich’s article helps to see the debate over representations and their sub-semantic features in a broader perspective, where code and processes are distinguished from semantically evaluated marks in the system. A dilemma over a continuum between processes and states are discussed. Essential questions: What is productivity and systematicity of language/thought? How do they depend on the compositionality of concepts? Can connectionism succeed in demonstrating both productivity and systematicity? What is a process and how to distinguish it from a state upon which it takes place? Seminar 14. No readings assigned for the last seminar. Outstanding questions from previous sessions are discussed, and the overall value of the course is assessed. Students are also instructed about how to obtain grades. Their feedback on course development, reading requirements, course level and other methodological and design issues for future instantiations of the course are asked for. Individual experiences of participants are collected in an informal atmosphere. Essential questions: Did the course fulfill your expectations? Do you feel individual philosophical/psychological theories were fairly treated? Could you follow a distinct line of development of the course or did individual classes seem a bit disparate? Would you advice your colleagues to take the course? IV Assessment Student participation, a presentation with a commentary and a paper are basic for credit and grade. Each student can miss two classes at maximum, otherwise credits cannot be given. Students are required to present an assignment in the form of a 15 to 20 minutes presentation of read materials. They should be able to reconstruct the argument, set it within the context of previous lectures and assess its strength. Another student is asked to give a brief, 5 minute commentary on their work, aiming primarily at demonstrating possible misinterpretation on the side of the presenter. Prior cooperation between presenter and commentator is therefore required and it greatly improves group unity and social interaction. Not presenting or commenting equals to failing the course and so does academic dishonesty. At the end of the semester papers are expected from each participant. 8-10 pages of their own research on a related topic is required, with less pages if the paper is in English. Originality, consistency, argumentative power and literature reviewed are assessed and grade determined. Due to the nature of open terms, papers are expected all the way through summer, with a deadline only in the 2nd half of September. V. Reading list Week 1 – Introduction, no readings Week 2 - Ryle, G.: The Theory of Meaning, Grice, P.: Meaning Revisited Week 3 - Burge, T.: Individualism and the Mental, McDowell, J.: Singular Thought and the Extent of the Inner Space Week 4 - Fodor, J.: Psychosemantics, ch. 2, Carruthers, P.: Russelian Thoughts Week 5 - Fodor, J.: A Modal Argument for Narrow Content, Burge, T.: Vision and Intentional Content Week 6 - Block, N.: Advertisement For A Semantics for Psychology, Loar, B.: Conceptual Role and Truth-conditions. Week 7 - Fodor, J. et al.: Against Definitions, Fodor, J.: Information and Representation Week 8 - Fodor, J.: Theory of Content, ch.4, Millikan, R.: Biosemantics Week 9 - Davidson, D.: Knowing One’s Own Mind, Stich, S.: What is a Theory of Mental Representation? Week 10 - Rosch, E.: Principles of Categorization, Carey, S and Spelke E.: Knowledge Acquisition Week 11 - Peacocke, C.: Can Possession Conditions Individuate Concepts?, Lakoff, G.: Cognitive Models and Prototype Theory Week 12 - Smolensky, P.: Connectionist Modeling, Rumelhart, D.: The Architecture of Mind Week 13 - Fodor, J. and Pylyshyn, Z.: Connectionism and Cognitive Architecture, Clark, A.: The Presence of a Symbol Week 14 – Assessment – no readings VI. Teaching Methodology Each 90-minute class is divided into a seminar part and a lecture part. In the first class of the semester students choose which week they will present their materials and which presentation they would like to comment on. From the second class on, each session starts with a student’s presentation of a selected course material. It is followed by a brief commentary from another student that highlights possible weak points of the presenter’s interpretation. Discussion follows in which debatable points of the coming lecture are stressed and a context of the presented paper is given. Emphasis is put on the interaction between the presenter and his/her commentator. This double role of students is extremely useful, as it requires them both to debate the issue in the time before the class and interact socially within the course group to a much larger degree than normally expected. With this background in mind, a delivered lecture then gives a broader perspective on the subject matter, situating the presented text in line with other course materials. Students are encouraged to ask question even during the lecture periods and their mutual involvement is greatly supported. Transparencies are sometimes used to make sense of schemas, presented in course readings. Additional reading materials outside of the scheduled listing are offered, especially to presenting students. Students are also supported in a search for any supplementary material on their own. Students are given the teacher’s email contact in order to facilitate interaction outside of classroom. No office hours are assigned, but due to the nature of the lecturer’s job (researcher), consultations are easy to set up. VII. Number of participating students Eight students altogether. Five philosophy graduates (3rd and 5th year), one doctoral student in philosophy and two psychology graduate students.