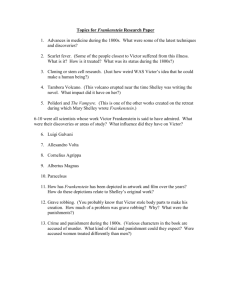

Frankenstein and the Pursuit of Knowledge in the

Nataly Baez- Writing Sample

Frankenstein and the Pursuit of Knowledge in the Romantic Era

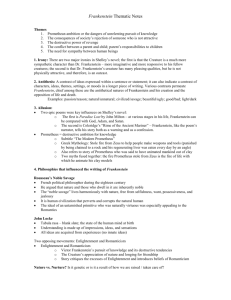

The pursuit of knowledge in a typical sense is not considered a sinful endeavor by most modern groups, though in history has been seen as a tricky ambition. While inventors and scientists have generally always been lauded for their discoveries, some portions of the population worried, and continue to do so, about the extent in which people are willing to go for such knowledge. Many stories have focused on the subject, including Doctor Faustus and The Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde but Mary

Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus remains amongst the most cited for its address of the topic. Shelley’s commentary on the quest for scientific knowledge beyond the human realm, its misuse and discovery based on solely selfish reasons rather than for the betterment of mankind, serves as a reproach to the Enlightenment, the cultural movement that encouraged the acquisition of knowledge and scientific advancement. In this way, Frankenst ein’s tale becomes one of a cautionary nature for those pursuing knowledge beyond their “realm” and for their own recognition.

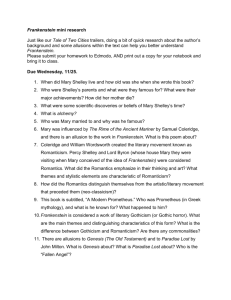

The Enlightenment made headway during the 17 th and 18 th centuries, under which the Scientific Revolution sprouted and scientific advancements and rationalism were promoted. During this time philosophers and scientists were encouraged to make use of the scientific method and were ultimately allowed more freedom in their endeavors. By the end of the 18 th century ideas of the Enlightenment were beginning to fade. Artists in particular reacted to the cultural movement with Anti-Enlightenment work and with the Romantic period. Romanticism served as a break from the Enlightenment period by encouraging the use of emotions, a delight in nature, spontaneity and aesthetic artistic developments. Most artists and intellectuals of this dawning period saw

2 the Enlightenment as artificial, cold and as a form of suffocating artistic expression.

Thus Romanticism became a means to escape the calculating realities of the Scientific

Revolution.

Mary Shelley’s ideas concerning the Enlightenment and knowledge may have derived from he r parent’s participation in the movement. William Godwin and Mary

Wollstonecraft both contributed to the Enlightenment period with their philosophical writing. Wollstonecraft in particular is considered an important figure during the

Enlightenment for her views on feminism. Her opinion was that females, despite popular notions of the time, were not biologically inferior to men and were only disadvantaged by their upbringing and their lack of academic opportunity. Godwin on the other hand focused on utilitarianism and the early blue prints of anarchism, ideas so radical it propagated physical attacks. Having been introduced to revolutionary ideas from prominent figures in the movement early on and her participation in Romanticism may have contri buted to Shelley’s troubled stance on the subject of knowledge.

Many critics suggest that Shelley’s apprehension towards scientific development of the sort Frankenstein pursues may be due to her gender. Frankenstein’s experiments sets out to create human life through unnatural means — without a woman. His ability to do so ultimately goes awry; this might imply that scientific reproduction or any reproduction that excludes the presence of a mother will fail. While many support this view within the context of her mother’s feminist writings, which would have influenced the highly educated Shelley, the birth and death of her infant child and her own pregnancy at the time of her writing (Franklin), some aspects of the novel undermine this view. The subtitle for instance implies the importance of forbidden knowledge rather

3 than the negative effects of masculine birth. Another example exists in Frank enstein’s monster’s desire for female companionship. The creature’s yearning for a bride and

Frankenstein’s decision to destroy the almost completed bride stems from her ability to reproduce, not the monster’s. If Shelley’s fear is of women becoming obsolete within the process of reproduction then would Frankenstein not have equipped his monster with the ability to reproduce asexually? If this were the case why would Frankenstein’s monster specifically need a female monster in order to build a family? Though there is evidence to support Shelley’s fear of masculine reproduction, most of it is not textual but within the context of her life.

Shelley’s ambivalence may stem from her parent’s participation and her own opinions on the pursuit of knowledge. While she does not chastise all scientific advancement, she does fear the effects of pursuing knowledge outside of the “human realm”. Victor Frankenstein’s desire to create life without the use of natural reproduction represents the pursuit of “forbidden knowledge” that Shelley feared— knowledge reserved for higher beings. By igniting life into an inanimate object, Frankenstein plays out the role of God without accepting the responsibility and consequences of his experimentations. The unraveling of his life and the lives of those he loves places his pursuit of knowledge in a negative light. But to Shelley the pursuit of knowledge is not a negative ambition, but once motivated by recognition and power becomes corrupted.

This sentiment becomes clear near the end of the novel when Victor states that where he has failed

“yet another may succeed” (Shelley 152). In saying this, Shelley condemns Victor’s approach but also indicates that had his quest been rooted in a

desire to better humankind rather than for his own “idealistic pride” (Hindle xxxii) it may not have been so disastrous.

4

The idea of forbidden knowledge is constant throughout the novel and throughout history. Romans, Greeks, and Abrahamic religions all have myths about forbidden knowledge given to humans despite the wills of the Gods, an act that results in severe punishment in every account. This knowledge is often represented as light or fire.

Shelley’s use of fire within the text, along with the subtitle of the novel alludes to these myths in her attempt to criticize Victor’s search for the forbidden, his misuse of science and for his quest for knowledge solely based on selfish reasons

. Frankenstein’s monster, viewing the world from a fresh perspective, understands fire as a source of enlightenment, a powerful tool but also as having the potential to burn him if touched or used incorrectly. But the parallels between fire and knowledge don’t end there. Fire can be described as the more extreme version of light, which is mentioned at intervals within the text in relation to Frankenstein and to Walton, who describes, depending on the interpretation the North Pole or the scope of scientific development as “a country of eternal light” (Shelley 1). Fire again is used as a symbol when Frankenstein’s monster vows to ignite his own funeral pyre. In this case fire literally consumes Frankenstein’s work, which adequately describes the effect of his pursuit of knowledge throughout the novel.

Shelley’s conflicting opinions on the quest for knowledge also becomes apparent through her contrasting depictions of Victor Frankenstein and Henry Clerval. While

Frankenstein is represented as a classic “Enlightened” individual, Clerval captures the basic characteristics praised by the Romantic period. Clerval, as opposed to

Frankenstein, is a poet and described as

“no natural philosopher” (Shelley). Aside from being a much more creative man than Frankenstein, he also seems to be a better friend. After Frankenstein’s creation of his creature he retreats back to his homeland and reunites with Clerval for the first time in several years. Until then Frankenstein had abandoned his family and his close friends in his pursuit of knowledge. Clerval, though concerned for Frankenstein’s well being, does not prod him with questions and seeks o nly to aid him. Ultimately, Frankenstein’s creature destroys Clerval, an act that in metaphoric language could foreshadow the effects of “forbidden knowledge” on the natural or the Romantic.

5

Frankenstein’s creature’s physical being also provides evidence of Shelley’s opinion on the pursuit of forbidden knowledge. What makes Victor’s creature a monster? Victor shirks his responsibility to his creation because of its hideousness.

Though he attempts to create a Gothic ideal — pale skin and dark hair— the outcome of

Frankenstein’s overreaching experimentation reveals his lack of understand of the natural and depreciation for the aesthetic. Frankenstein, who devotes his life to scientific endeavors unlike his close friend, Clerval, ultimately creates a shadow or double of himself. Much like in the role he is playing of God, he creates his creature in his image but his image reflects his refusal of Romantic ideals, one of which is natural beauty.

Therefore, the creature’s lack of Romantic beauty becomes the root of the disaster.

Perhaps if Victor could have embraced some Romantic ideals or at least had the betterment of humankind in mind, his creation would have been beautiful and therefore not considered a monster (Bloom 614). Had that transpired, Frankenstein would have

6 taken responsibility for his experiment and raised him correctly, but only with the infusion of Enlightenment and Romantic ideals.

Mary Shelley’s creation best reflects her opinions on the Enlightenment and the

Romantic era. While in her private life Shelley condemned traditional Romanticism, her novel serves as a rejection of extreme Enlightenment ideals. Her text encourages a balance between the two movements; her assertion that one day someone may create life successfully, and not just reanimate the dead leads us to believe that she did not spurn all scientific advancements but only those that sought out knowledge that she felt were outside of humanity’s right. Frankenstein walks a dangerous road to knowledge, one that exceeds the human realm. His failures derive from his inability to balance his own Enlightenment ideals with that of the Romantic period. Had he not set out to create life under the spell of power and recognition (Lunsford 175), had he embraced some

Romantic ideals of beauty and thus created beauty, had he been content to study that which was available to him and not overreach by playing the role of God, maybe his creation would have been his proud legacy instead of an abandoned, conflicted abomination.

Citations

7

Bloom, Harold. "An Excerpt from a Study of "Frankenstein: Or, The New Prometheus."

Partisan Review 32.4 (1965): 611-18. Web.

Franklin, Ruth. "Was ‘Frankenstein’ Really About Childbirth?" The New Republic. The

New Republic, 7 Mar. 2012. Web. 23 Apr. 2013.

Hindle, Maurice. Introduction. Introduction. By Mary Shelley. London: Penguin Classics,

2003. Xxxii. Print.

Lundsford, Lars. "The Devaluing of Life in Shelley’s FRANKENSTEIN." The Explicator

68.3 (2010): 174-76. Print.

Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft. Frankenstein or the Modern Prometheus. New York:

Random House, 1982. Print.