the clinical application of 4d 18f-fdg pet/ct on gross tumor volume

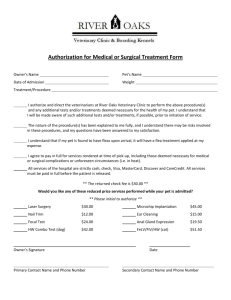

advertisement

1 THE CLINICAL APPLICATION OF 4D 18F-FDG PET/CT ON GROSS TUMOR VOLUME DELINEATION FOR RADIOTHERAPY PLANNING IN ESOPHAGEAL SQUAMOUS CELL CANCER Yao-Ching Wang1,2 , Chia-Hung Kao 3,4, Te-Chun Hsieh4,5, Shang-Wen Chen1,3, Chun-Ru Chien1,3, Chun-Yen Yu1,5, Kuo-Yang Yen4,5, , Shih-Neng Yang1,5, Yu-Cheng Kuo1,3, Shih-Ming Hsu6, Tinsu Pan7, Ji-An Liang1,3 Affiliation 1 Department of Radiation Oncology, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan; 2 School of Medicine, Graduate Institute of clinical Medical Science, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan; 3School of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan, 4Department of Nuclear Medicine and PET Center, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan; 5 Department of Biomedical Imaging and Radiological Science, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan; Biomedical Imaging and Radiological Science, China Medical University, Taiwan; 7 University of Texas MD Anderson cancer center Address correspondence and/or reprint requests to: Ji-An Liang, MD, Department of Radiation Oncology, China Medical University Hospital, No. 2, Yuh-Der Road, Taichung 404, Taiwan. TEL: 886-4-22052121-7461; FAX: 886-4-22339372; E-mail: d4615@mail.cmuh.org.tw 2 Running title: 4D PET/CT-based gross tumor volume in esophageal cancer Abstract Objectives: To estimate the feasibility of the combined four-dimensional computed tomography with four-dimensional 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (4D CT-FDG PET) in gross tumor volume (GTV) delineation of esophageal cancer. Methods: Eighteen patients with esophageal cancer eligible for radical surgery or definitive radiotherapy were prospectively enrolled. In 4D images during respiratory cycle, an average phase of CT images was fused with average phase of FDG PETs for analysis of optimal standardized uptake values (SUV) or threshold. PET-based GTV (GTVPET) was determined with 8 different threshold methods by autocontouring function at the PET workstation. The difference in volume ratio (VR) and conformality index [1] between GTVPET and CT based GTV (GTVCT) was investigated. Results: The image sets via automatic co-registrations of 4D CT-FDG PET were available in 12 patients with 13 GTVCT. The decision coefficient (R2) of tumor length difference at the threshold levels of SUV2.5, SUV20% and SUV25% were 0.79, 0.65 3 and 0.54, respectively. The mean volume of GTVCT was 29.41 ± 19.14 mL (range, 3.65 to 70.76 mL). The mean VR ranged from 0.30 to 1.48 (0.86±0.24). The optimal VR, 0.98 , close to 1, was at SUV 20% or SUV 2.5. The mean CI ranged from 0.28 to 0.58. The best CI was at SUV 20% (0.58) or SUV 2.5 (0.57). Conclusions: The autocontouring function by SUV threshold has the potential for assisting the contouring the GTV in radiation planning for esophageal cancer. The SUV threshold setting of SUV 20% or SUV 2.5 achieves the optimal correlation in tumor length, VR and CI using 4D-PET/CT images. Introduction The use of 18Fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) in radiotherapy (RT) provides a supplement of this already interdisciplinary process to include information on the biologic status of tumors, which is complementary to conventional computed tomogram (CT) images and may result in a change of the tumor volume delineation[2]. RT is an important part of the multidisciplinary treatment in esophageal cancer (EC) , but tumor control and overall survival are still disappointed [3]. 18F-FDG PET has been shown to improve the staging of EC [4, 5]. Particularly, several studies suggested PET overlay on CT has shown to have some 4 impact on the definition of the gross tumor volume (GTV), decrease inter-observer variability and change the treatment planning. [6-8]. However, when radiation oncologists contour the GTVs on a fused PET and CT image or an integrated PET/CT, a problem appears in setting the appropriate threshold for the PET. Despites several investigations declared autocontouring or manual contouring of the PET-based tumor volume results in a change of the GTV compared to CT-based GTV[9-11], some standards should be followed for the PET/CT–based tumor delineation.. The published methods based on a threshold determined as a percentage of the maximal standardized uptake value (SUVmax) have used values ranging from 15% to 50% for non-small-cell lung cancer [12-14]. Similarly, there was a great variations of validated standardized methods for EC in setting this threshold [7, 15-17]; these include using mean activity in the liver plus various standard deviation, the various absolute standardized uptake value (SUV) (i.e., GTV = SUV of ≧2), or using percentages of the SUVmax (i.e., GTV = volume encompassed by ≧ 25% the SUVmax). Organs or tumor motion always influenced the accuracy and quality of CT images in the thoracic malignancy, including EC during free breathing cycle. Concern should be taken when considering the extent of tumor motion and different spatial tumor position by four-dimensional (4D) CT as described in non-small-cell lung 5 cancer [18, 19]. A recent study reported EC moved with respiratory cycle, especially at lower third and in the cranial-caudal direction. [20]. Respiratory 4D PET/CT techniques are highly useful in target volume definition accurately representative of organ and lesion motion despite the real benefits of clinical outcome need further investigation [21]. It is still unknown about the feasibility of implementing four-dimensional PET/CT (4D-PET/CT) in determining the GTV for EC. Thus, there is a need to conduct a pilot study by using 4D-PET/CT in contouring. We hypothesized that some standards can be obtained when defining GTV for EC by using biological target volume from 4D-PET/CT images. This prospective study was conducted to evaluate the feasibility of 4D-PET/CT simulation in RTO planning for esophageal cancer. Also, appropriateness of the percentage threshold method would be investigated for determining the best volumetric match between PET-based and CT-based GTV when contouring primary tumor volume of esophageal cancer. Materials and Methods Patients This study was a prospective analysis, approved by local institutional review 6 board (DMR98- IRB-171), of 4D-PET/CT in radiotherapy planning of esophageal cancer. Patients with histologically approved esophageal cancer who would undergo definitive radiotherapy, concurrent chemoradiotherapy or radical surgery were eligible for this study. Eighteen patients with esophageal squamous cell cancer were enrolled between December 2009 and January 2011. The image data from 12 patients with 13 GTVCT were available for this study and were analyzed. The median age was 48.5years (range, 38-76 years). All patients were men. The characteristics of these patients included are presented in Table 1. PET-CT image acquisition All patients were asked to fast for at least 4 hours before 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging. Each of them was administered intravenously with 370 MBq (10 mCi) of 18F-FDG and rested supine in a quiet and dimly room. All images were acquired with an integrated PET/CT scanner (Discovery STE, GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). Scanning began 40 minutes after injection of FDG. Arms were elevated above the head. Staging whole body PET/CT images were taken first according to the standardized protocol. The CT images were reconstructed onto a 512×512 matrix and converted to a 128×128 matrix, 511-keV-equivalent attenuation factors for attenuation correction of the corresponding PET emission images. Immediately after whole body 7 PET/CT images, patients were repositioned and simulated in a radiotherapy planning position using the Real-time Position Management (RPM) system respiratory gating hardware (Varian Medical Systems Inc, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Four-dimensional CT images with 2.50-mm slice thickness, and 4D PET images with two table positions, 7 minutes per position, were acquired. The respiration cycle was divided in 10 phases each other. All CT images were automatically sorted by 4D software (Advantage 4D, GE, Healthcare). The images were transferred from the PET/CT workstation via DICOM3 to the RTP (Eclipse version 8.6, Varian Medical System Inc, CA, USA) for GTV delineation. All phases of CT images and PET images were automatically fused for this gating study. PET/CT-based GTV of the primary tumor (GTVPET) was defined by autocontouring function at the AW workstation (Advantage SimTM 7.6.0, GE, Healthcare), either applying the isodensity volumes by adjusting different percentage of the maximal threshold levels, or simply using a fixed value of SUV. The threshold strategies for assessing the optimized SUV for GTV contouring were derived from other investigation [7, 8, 16, 22]. Eight different threshold methods were used in this study. They were SUV 15%, SUV 2, SUV 2.5, SUV 20%, SUV 25%, SUV 30%, SUV 40% and SUV 50%. The length of the GTVPET provided by autocontouring function was not changed at all. All the artifacts within the GTVPET, including the area overlaid with heart, bone and great vessels, were excluded manually in the RTP system (figure 8 1). CT-based GTV definition The PET temporal resolution is an average of several respiratory cycles. In contrast to the helical CT, the temporal resolution of averaged CT (ACT) is comparable with PET. Furthermore, Chi et al. demonstrated respiration artifacts in PET from PET/CT can be minimized with ACT, and ACT was temporally and spatially consistent with the PET [23] . On the basis of axial ACT images, contouring of the tumor volume and critical structures was performed without knowing PET results in an effort to reduce bias. The information of tumor extent from the contrast CT scan, panendoscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) were used when delineating the GTVCT. Excluding the adjacent metastatic lymph nodes, the volume of primary tumors (GTVCT) was contoured as a reference tumor volume. To reduce inter-observer variations, at least 2 different radiation oncologists carried out the contouring of the tumors for each patient. Conformality index and volume ratio comparison After the completion of the GTVCT contouring in RTP system, the radiation oncologists reviewed the consistency of PET/CT images with nuclear medicine 9 physicians. The volume of GTVCT and GTVPET was compared by conformality index [1] and volume ratio (VR). CI is the ratio of the volume of intersection of two volumes (A∩B) compared with the volume of union of the two volumes (A∪B) under comparison [ CI = A B ][22, 24]. VR is the ratio of two volumes, and the A B denominator is the volume of GTVCT. A suitable threshold level could be defined when GTVPET was observed to be the best fitness of the length, CI or VR from the GTVCT. Statistical analysis All statistical test were performed using the SPSS 15 (SPSS Chicago,IL), each GTVs were analyzed by one-way ANOVA test with the post hoc test by scheffe method, and a P-values ≦0.05 were considered statistically significant. Pearson correlation was performed to assess the correlation of tumor length of the GTVCT with that of the GTVPET. Results Of the 18 patients, automatic co-registrations of 4D-PET/CT were successful in 13 tumors from 12 patients. In 6 patients, the fused images were not available for the analysis. One had small T1 tumor which could not be detected by PET scan. A 10 SUVmax was 2.96 in another patient with T1 lesion, and he was not suitable for further analysis. Because of different table positions between 4D-PET and 4D-CT, fusion failure occurred in the first patient enrolled this study. The other two patients were excluded due to irregular respiration rhythms, which caused failure in image fusion. One patient was also excluded, because of diffuse lung and bone metastatic status. Autocontouring function for GTVPET was insufficient for primary GTV delineation. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 13 patients. The histological type for all the patients was squamous cell carcinoma. The median age were 48.5 (range, 38-76). Eleven lesions (85%) were T3 and T4 stage. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was performed for 9 patients (75%). The mean length of GTVCT was 5.73 ± 2.40cm (range, 1.75-10.01cm). The mean volume of GTVCT was 29.41 ± 19.14mL (range, 3.65-70.76 mL). The mean SUVmax was 13.26 ± 2. 78 (range, 9.4-16.9). Figure 2 shows the results of the mean tumor lengths on CT (CT mean tumor length by different SUV thresholds (PET length). length) and the Figure 3 illustrates the correlation of CT length compared with PET length at SUV2.5, SUV 20% and SUV25%. The decision coefficient (R2) of tumor length difference at the threshold levels of SUV2.5, SUV20% and SUV25% were 0.79, 0.65 and 0.54, respectively. The mean VR ranged from 0.30 to 1.48 (0.86±0.24) (F = 29.34, P < 0.001). Mean VR at 11 different SUV threshold levels are shown in Figure 4. The VR values gradually decreased from SUV15% to SUV50%. The best fitness for VR was found at SUV 20% (mean SUV 2.65 ± 0.56) and SUV 2.5, and achieved the most optimal VR value 0.98 ± 0.24 and 0.98 ± 0.26, respectively. The VR at SUV40% (0.41 ± 0.14) or SUV50% (0.30 ± 0.12) were not an ideal threshold level for GTV contouring of esophageal cancer. The mean CIs ranged from 0.29 to 0.58 (F = 11.34, P < 0.001). Mean CI at different SUV threshold levels are shown in Figure 5. The best fitness for CI was at SUV 20% (0.58 ± 0.10) or SUV 2.5 (0.57 ± 0.13). Discussion This work was a pilot study to investigate the feasibility of 4D-PET/CT when contouring the GTV for EC. By comparing eight interested threshold levels, the result showed the GTVPET using a threshold setting of SUV 20% or SUV 2.5 correlated well with tumor length, VR and CI of the GTVCT. The result was compatible with previous studies which investigated the optimal contouring threshold by using non-respiratory controlled PET or PET/CT [6, 8, 16, 22]. Zhong et al. presented the FDG GTVPET at SUV2.5 provided the closest estimation of gross tumor length in EC [16]. Han et al. reported a study of combined 18 F-flurorothymidine (FLT) and FDG PET/CT in assessing the feasibility of GTV delineation in EC and found a threshold setting of 12 SUV1.4 on FLT PET/CT or SUV2.5 on FDG PET/CT was correlated well with the pathologic GTV length [8]. When using a threshold level of SUV 40%, the PET-based tumor length was obviously underestimated to the pathologic length [8, 16]. Similarly, based on the result of our study, a threshold setting with SUV ≧ 30 % is not adequate for the autocontouring. To optimize the GTV contouring for EC, panendoscopy, EUS and CT images were usually used for the information regarding the precise tumor location and volume. Nonetheless, panendoscope and EUS cannot pass through the obstructive lumen in locally advanced tumors. In this situation, the actual location regarding distal margin of tumor should be interpreted by CT image only. However, the precise tumor length and extent are not always discernible because the mucosa or submucosa lesions might not be visualized by CT scan. Konski et al. reported that EUS finding correlated well with PET-based tumor length than that with CT scans in a series of 25 patients [6]. The International Atomic Energy Agency expert group promised 18 F-FDG PET/CT provides the best available imaging for accurate target delineation in RT planning [25]. With the implementation of PET/CT, the risk of geographic miss, underdosing and normal tissue complication probability might be reduced [10]. Certainly, the use of FDG-PET/CT for GTV delineation for RT planning should be 13 validated based on loco-regional control and survival in the future [26]. Four-dimensional CT in target volume delineation and motion were well studied in non-small-cell lung cancer, including fractionationated radiotherapy and stereotactic radiotherapy [18, 19], but there was a paucity in investigating esophageal motility during RT. Dieleman et al. reported a retrospective study of analyzing 29 patients with nonesophageal cancer, mostly stage 1 lung cancer, using 4D-CT [27]. They suggested that distal esophagus had the largest motion margins with 9 mm in medio-lateral direction and 8 mm in dorso-ventral direction. PET is generally performed in the free breathing status without breath-hold or respiratory gating techniques, so PET is an average image obtained during several respiratory cycles. Therefore, FDG quantification, tumor margin definition and smaller tumor detection can be improved with the application of respiratory gating or 4D-PET [1, 28]. Chi et al. demonstrated respiration artifacts in PET from PET/CT could be minimized with ACT, and ACT was temporally and spatially consistent with the PET [23]. Based on this concept, we assumed that the GTV contouring using an average phase of images on 4D-CT would minimize the impact of tumor motion when they were fused with the PET. Several studies have explored the use of a fixed or adaptive threshold setting for 14 accurate tumor dimensions in thoracic cancer [8, 12, 22], but no study reported comprehensive parameters, including the VR, CI and tumor length when compared to the GTVCT. Probably, it might be attributed to the complexity of organ motion and uncertainty of image registration. Hanna et al. investigated the impact of PET/CT simulation for GTV definition in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by using the concordance index (equivalent to CI in our study) [29]. The mean concordance index of their study was 0.64 and 0.57 in GTVPET-CT and GTVCT, respectively. This indicated a significant reduction in inter-observer variation by adding PET in GTV delineation. In EC study, Vali et al. compared a short long segment of esophageal the GTVPET and GTV CT and EUS of EC at the level of the tumor epicenter and found a threshold setting of SUV2.5 and SUVL4σ ( equal to SUV2.4) resulted in the highest CI value (0.48 and o.47, respectively) [22]. Gondi et al. demonstrated the values CI of NSCLC and EC with the incorporation of FEG-PET and CT were 0.44 and 0.46, respectively [24]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that compared the CI value between the GTVPET and GTV CT using 4D PET/CT in contouring EC and using whole tumor volume. Our results were similar to the studies mentioned above. The CIs of our study implied approximately 75% overlapping in the two volumes. The CI levels of SUV40% or 50% were inferior to to the other thresholds, and were not ideal for autocontouring of the GTVPET. Furthermore, the VR was close 15 to 1 at SUV 20% or SUV 2.5, it was better than the other studies of partial VR of EC [22] and the VR of NSCLC[12]. When using smaller cutoff values, such as SUV2 or SUV 15% in threshold setting, more adjacent normal tissue would be included within the GTVPET. Thus, primitive values of CI or VR were changed and became better when some artifacts were corrected. But, this manual procedures were very time -consuming. Our result should be interpreted with two limitations. First, the study was based on the comparison of the GTVCT and GTV PET without knowing the pathologic information about the tumor length, axial extent, and real volume. Certainly, the biological volume could not be definitely related to the real tumor volume. Similarly, the GTVCT could identify areas without the tumor tissue. Because of the popularity of using neoadjuvant or definitive CCRT in treating EC [3, 30], it seems difficult to perform a direct pathologic comparison from the surgical specimen. Second, it is not flawless that the averaged phase of 4D-CT images fused with the averaged PETs was used to delineate the GTVs. This approach might provide more accurate functional images supplemental to CT without increasing the clinical overwork during contouring; however, the actual impact of tumor motion from maximum intensity projection should be investigated further. In addition, lower resolution of PET images 16 than CT images might limit the results of this study. Conclusion This study demonstrated that 4D-PET/CT is applicable when contouring the GTV in radiation planning for esophageal cancer. The use of threshold levels of SUV 20% or SUV 2.5 achieves the optimal correlation with tumor length, VR and CI. To assess final treatment outcome, the benefits of RT planning using 4D-PET/CT need more clinical investigations. REFERENCES 1. Garcia Vicente AM, Soriano Castrejon AM, Talavera Rubio MP, Leon Martin AA, Palomar Munoz AM, Pilkington Woll JP, et al. (18)F-FDG PET-CT respiratory gating in characterization of pulmonary lesions: approximation towards clinical indications. Annals of nuclear medicine. 2010;24(3):207-14. 2. Gregoire V, Haustermans K, Geets X, Roels S, Lonneux M. PET-based treatment planning in radiotherapy: a new standard? Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2007;48 Suppl 1:68S-77S. 3. Berger B, Belka C. Evidence-based radiation oncology: oesophagus. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic 17 Radiology and Oncology. 2009;92(2):276-90. 4. van Westreenen HL, Westerterp M, Bossuyt PM, Pruim J, Sloof GW, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Systematic review of the staging performance of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(18):3805-12. 5. Noble F, Bailey D, Tung K, Byrne JP. Impact of integrated PET/CT in the staging of oesophageal cancer: a UK population-based cohort study. Clin Radiol. 2009;64(7):699-705. 6. Konski A, Doss M, Milestone B, Haluszka O, Hanlon A, Freedman G, et al. The integration of 18-fluoro-deoxy-glucose positron emission tomography and endoscopic ultrasound in the treatment-planning process for esophageal carcinoma. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2005;61(4):1123-8. 7. Yu W, Fu XL, Zhang YJ, Xiang JQ, Shen L, Jiang GL, et al. GTV spatial conformity between different delineation methods by 18FDG PET/CT and pathology in esophageal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93(3):441-6. 8. Han D, Yu J, Yu Y, Zhang G, Zhong X, Lu J, et al. Comparison of (18)F-fluorothymidine and (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT in delineating gross tumor volume by optimal threshold in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of thoracic esophagus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(4):1235-41. 9. Hong TS, Killoran JH, Mamede M, Mamon HJ. Impact of manual and automated interpretation of fused PET/CT data on esophageal target definitions in radiation planning. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(5):1612-8. 10. Muijs CT, Schreurs LM, Busz DM, Beukema JC, van der Borden AJ, Pruim J, et al. Consequences of additional use of PET information for target volume delineation and radiotherapy dose distribution for esophageal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93(3):447-53. 11. Moureau-Zabotto L, Touboul E, Lerouge D, Deniaud-Alexandre E, Grahek D, Foulquier JN, et al. Impact of CT and 18F-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography image fusion for conformal radiotherapy in esophageal carcinoma. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2005;63(2):340-5. 18 12. Wu K, Ung YC, Hornby J, Freeman M, Hwang D, Tsao MS, et al. PET CT thresholds for radiotherapy target definition in non-small-cell lung cancer: how close are we to the pathologic findings? International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2010;77(3):699-706. 13. Biehl KJ, Kong FM, Dehdashti F, Jin JY, Mutic S, El Naqa I, et al. 18F-FDG PET definition of gross tumor volume for radiotherapy of non-small cell lung cancer: is a single standardized uptake value threshold approach appropriate? Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2006;47(11):1808-12. 14. Yu J, Li X, Xing L, Mu D, Fu Z, Sun X, et al. Comparison of tumor volumes as determined by pathologic examination and FDG-PET/CT images of non-small-cell lung cancer: a pilot study. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2009;75(5):1468-74. 15. Vesprini D, Ung Y, Dinniwell R, Breen S, Cheung F, Grabarz D, et al. Improving observer variability in target delineation for gastro-oesophageal cancer--the role of (18F)fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2008;20(8):631-8. 16. Zhong X, Yu J, Zhang B, Mu D, Zhang W, Li D, et al. Using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to estimate the length of gross tumor in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2009;73(1):136-41. 17. Mamede M, El Fakhri G, Abreu-e-Lima P, Gandler W, Nose V, Gerbaudo VH. Pre-operative estimation of esophageal tumor metabolic length in FDG-PET images with surgical pathology confirmation. Ann Nucl Med. 2007;21(10):553-62. 18. Hof H, Rhein B, Haering P, Kopp-Schneider A, Debus J, Herfarth K. 4D-CT-based target volume definition in stereotactic radiotherapy of lung tumours: comparison with a conventional technique using individual margins. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93(3):419-23. 19. Rietzel E, Liu AK, Doppke KP, Wolfgang JA, Chen AB, Chen GT, et al. Design of 4D treatment planning target volumes. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2006;66(1):287-95. 19 20. Yamashita H, Kida S, Sakumi A, Haga A, Ito S, Onoe T, et al. Four-dimensional measurement of the displacement of internal fiducial markers during 320-multislice computed tomography scanning of thoracic esophageal cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2011;79(2):588-95. 21. Bettinardi V, Picchio M, Di Muzio N, Gianolli L, Gilardi MC, Messa C. Detection and compensation of organ/lesion motion using 4D-PET/CT respiratory gated acquisition techniques. Radiother Oncol. 2010;96(3):311-6. 22. Vali FS, Nagda S, Hall W, Sinacore J, Gao M, Lee SH, et al. Comparison of standardized uptake value-based positron emission tomography and computed tomography target volumes in esophageal cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2010;78(4):1057-63. 23. Chi PC, Mawlawi O, Luo D, Liao Z, Macapinlac HA, Pan T. Effects of respiration-averaged computed tomography on positron emission tomography/computed tomography quantification and its potential impact on gross tumor volume delineation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71(3):890-9. 24. Gondi V, Bradley K, Mehta M, Howard A, Khuntia D, Ritter M, et al. Impact of hybrid fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography/computed tomography on radiotherapy planning in esophageal and non-small-cell lung cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2007;67(1):187-95. 25. MacManus M, Nestle U, Rosenzweig KE, Carrio I, Messa C, Belohlavek O, et al. Use of PET and PET/CT for radiation therapy planning: IAEA expert report 2006-2007. Radiother Oncol. 2009;91(1):85-94. 26. Muijs CT, Beukema JC, Pruim J, Mul VE, Groen H, Plukker JT, et al. A systematic review on the role of FDG-PET/CT in tumour delineation and radiotherapy planning in patients with esophageal cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2010;97(2):165-71. 27. Dieleman EM, Senan S, Vincent A, Lagerwaard FJ, Slotman BJ, van Sornsen de Koste JR. Four-dimensional computed tomographic analysis of esophageal mobility during normal respiration. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67(3):775-80. 28. Lupi A, Zaroccolo M, Salgarello M, Malfatti V, Zanco P. The effect of 18F-FDG-PET/CT respiratory gating on detected metabolic activity in lung lesions. Ann Nucl Med. 2009;23(2):191-6. 20 29. Hanna GG, McAleese J, Carson KJ, Stewart DP, Cosgrove VP, Eakin RL, et al. (18)F-FDG PET-CT simulation for non-small-cell lung cancer: effect in patients already staged by PET-CT. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77(1):24-30. 30. Gebski V, Burmeister B, Smithers BM, Foo K, Zalcberg J, Simes J. Survival benefits from neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy in oesophageal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(3):226-34.