ABI - Ships Project

advertisement

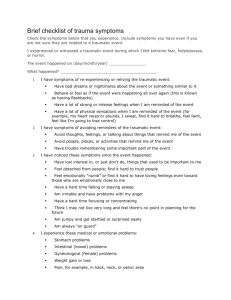

What is Acquired Brain Injury? All injuries to the brain, suffered after the period immediately following birth, are termed acquired brain injuries (ABI). These fall into two groups: traumatic and non–traumatic. ABI (Acquired Brain Injury) TBI (traumatic brain injury) e.g. Road traffic accidents, sports injuries, falls, shaken baby syndrome. Non-TBI (non-traumatic brain injury) e.g. meningitis, encephalitis, viral infection, ecoli, brain tumour, stroke Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) are the result of a medical trauma, or blow to the head. Such a head injury can be either closed or open. In this country we rarely see an open head injury, which is often the result of a gunshot wound, but closed head injuries caused by the head striking a hard surface, falling or suffering abuse, eg shaken baby syndrome. Non-traumatic injuries are not congenital or birth injuries, but include the results of diseases such as meningitis, encephalitis and viral infections, brain tumours and strokes. Currently there is a move away from the term head injury to brain injury, emphasising the continuing difficulties experienced with brain function. TBI has two different effects on the brain. Focal injury, either fracture or contusion (bleed), results from the impact, both the knock (coup) and the rebound blow (countercoup) of the brain inside the skull. Diffuse injury results from sudden acceleration or deceleration of the brain causing axonal shearing. These are called primary effects and neither of these is present for a non-traumatic ABI, but the secondary effects in TBI may be present in non-traumatic ABI. These include swelling of the brain or around the brain, contusions, haematomas or haemorrhage. Incidence It is not easy to state the number of young people who are brain-injured in the UK. A number of researchers have attempted to gather such information (eg Royal Hawley et al. 2004, PetitZeman 2001), the most recent suggesting that, every year, approximately 280 in every hundred thousand under-14-year-olds suffer a traumatic brain injury (TBI), in addition to the non-traumatic injuries, amounting to around 30,000 children per year gaining a new brain injury. In total, this amounts to between a quarter and half a million under 16 year olds in the UK with an ABI. Severity Not all brain injuries are severe. Medical severity is measured by the Glasgow Coma Score; severe injury is scored at less than 8, moderate injury is between 8 and 13 and mild injury 13-15. The length of coma measured in days may also be an indicator of severity, as can the length of Post Traumatic Amnesia (PTA), the period of confusion after an injury. Mild injuries are less than 1 hour in PTA, moderate injuries are 1-24 hours, severe are between 24 hours and 2 weeks. Very severe injuries are in PTA from 2 to 4 weeks and extremely severe cases more than 4 weeks. GCS PTA Mild Moderate Severe Very severe Extremely severe 12-14 <1 hour 8-12 1 -24 hours <8 1-14 days 2-4 weeks >4 weeks GCS - Glasgow Coma Score PTA - Post Traumatic Amnesia These measures are important as over stimulation while a child is still in PTA may lead to behaviour problems which otherwise would not have emerged (Ponsford 1995). However, severity measured by GCS and PTA is not a reliable indicator of consequences (Savage 1991, Blosser & DePompei 2003). Outcome Outcomes range from death and persistent vegetative states, to physical and cognitive disabilities and nearly always reflect the severity of the injury. Most children survive but are left with long-term ‘hidden’ problems with learning, behaviour and emotional understanding. All these children return to school, yet there is little or no information available to help their teachers, their parents or other professionals, who are often ill-prepared to deal with the difficulties that are frequently faced. (HIRE Newsletter Spring 2002) After severe brain injury children often lose all learning. Unable to speak or move they have to be retaught from the beginning. It is widely held that after Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) children can access all the learning which they had acquired prior to the injury, but it is extremely difficult to add to this learning. Such children often spend several months being taught at home by teachers of the hospital education service. Then there is a phased return to the classroom, either in their previous school or in a new school. It is at this point, when their learning can no longer be individually tailored, that the difficulties of the TBI child are compounded. The pupil may sit quietly in the classroom, appearing to act like the ‘average’ child but underneath there are great problems and teachers have to work hard to maximise their learning potential. Periods of dramatic change occur immediately after injury (acute phase), or within one year of injury (middle phase). After this point the rate of recovery slows down, but does not stop for up to 10 years, and the young person enters the chronic phase. However recovery is usually incomplete. There are improvements, and pupils 43/45 Stanley Road, Warmley, Bristol BS15 4NX 2 further from injury are more likely to have specific rather than global deficits. This is important for schools as secondary- aged pupils may be 6 years or more post-injury. No two children are the same; they were not the same before their accident and the damage which results from a brain injury depends on the type and extent of the damage, the location within the brain and the age of the child. Outcome is also determined by the environment of the child, their home background and support they receive, including educational support. Research Much work has been by medical researchers especially in the USA to isolate the consequences of TBI rather than the more general ABI, this may be because TBI is seen as an amorphous group within ABI, while non-traumatic ABI may be divided into further groups by aetiology. Yet the injuries from blows to different parts of the brain can also be quite different especially those involving the frontal lobes as opposed to other areas. In the classroom there is sufficient similarity to group all pupils with ABI together. As yet few educational researchers have considered the teaching/learning implications of ABI, although there is much work currently being undertaken. It is clear that pupils who have sustained an ABI do not learn in the same way as the majority of children. They seem unable to engage fully in the classroom processes of teaching and learning. This has major implications for their reintegration into the classroom. Rehabilitation However, it is held that it is better to deliver rehabilitation therapies in meaningful contexts for the child (e.g. Telzrow 1987, Semrud-Clikeman 2001) and schools play a major role in the rehabilitation of head-injured children, (Ewing-Cobbs et al. 1986 p 63) The difficulty for teachers is that the disability resulting from ABI frequently is invisible. Like dyslexia and mild autism, it is easy to forget about it in the hurly burly of classroom life and assume that the child is operating like the rest of the class. In addition, children with ABI may reach the same achievement level as their classmates and therefore are not flagged up as having Special Educational Needs. But they do not reach their potential. The Department for Education admitted: Mainstream schools and, indeed, many educational psychologists are unlikely to be knowledgeable about the special problems involved in recovery from serious illness or injury… In particular, even the most skilled mainstream teacher who has had no previous experience of teaching a brain injured child will need advice on potential changes in a child’s language, memory and organisational skill (which may be misunderstood or mishandled) (DfE May 1994 Paragraph 63) Most schools have no knowledge of the specific needs of a head-injured child and many would say that they have no head-injured children among their pupils. Certainly until I worked as a ward teacher at Frenchay Hospital I had not knowingly come across a head injured child in 20 years of teaching. 43/45 Stanley Road, Warmley, Bristol BS15 4NX 3 Most young people make a rapid physical recovery, which then creates expectations in parents and schools for adequate cognitive and behavioural functioning, but a normal physical appearance can mask underlying cognitive deficits. It is not just that older children with ABI act like younger children and follow the same developmental path, albeit slightly later, there actually is no evidence that the further development of the brain proceeds normally after injury. Teachers cannot assume that, by approaching a learner with ABI as they would a younger pupil, learning will proceed without hindrance. . Many young people who sustain a brain injury during their developing years do not reach their potential, because of the subtle differences in learning style and the particular difficulties these children experience. Bibliography and suggested reading Blosser, J.L. & DePompei R (2003) Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: Proactive intervention New York: Delmar Learning Hawley, C.A., Ward, A.B., Magnay, A.R. & Long, J.(2004) Outcomes following childhood head injury: a population study Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 75, 737-742 Hawley, C.A., Ward, A.B., Magnay, A. R. & Long, J. (2002) Children’s brain injury: a postal follow up of 525 children from one health region in the UK Brain Injury Vol 16, No 11, 969-985 Petit-Zeman, S. (2001) Missing out: The lifelong impact of children’s acquired brain injury CABIIG Ponsford, J. (1995) Traumatic Brain injury Rehabilitation for Everyday Adaptive Living Hove: Psychology Press Ylvisaker, M. (1998) (ed) Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation: Children and Adolescents Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann Savage, R. (1991) Identification, classification and placement issues for students with traumatic brain injuries Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation 6 (1) 1-9 Semrud-Clikeman, M. (2001) Traumatic Brain Injury in Children and Adolescents: Assessment and intervention Guildford Press Walker, S. & Wicks, B. (2005) Educating children with acquired brain injury London: David Fulton Video ‘Must Try Harder’ available from Encephalitis Society, SHIPS or Cbit © SHIPS Project August 2007 43/45 Stanley Road, Warmley, Bristol BS15 4NX 4