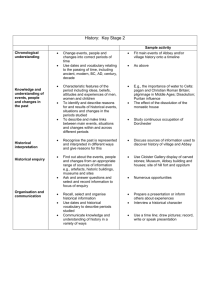

The study of monastic households and financial administration

advertisement

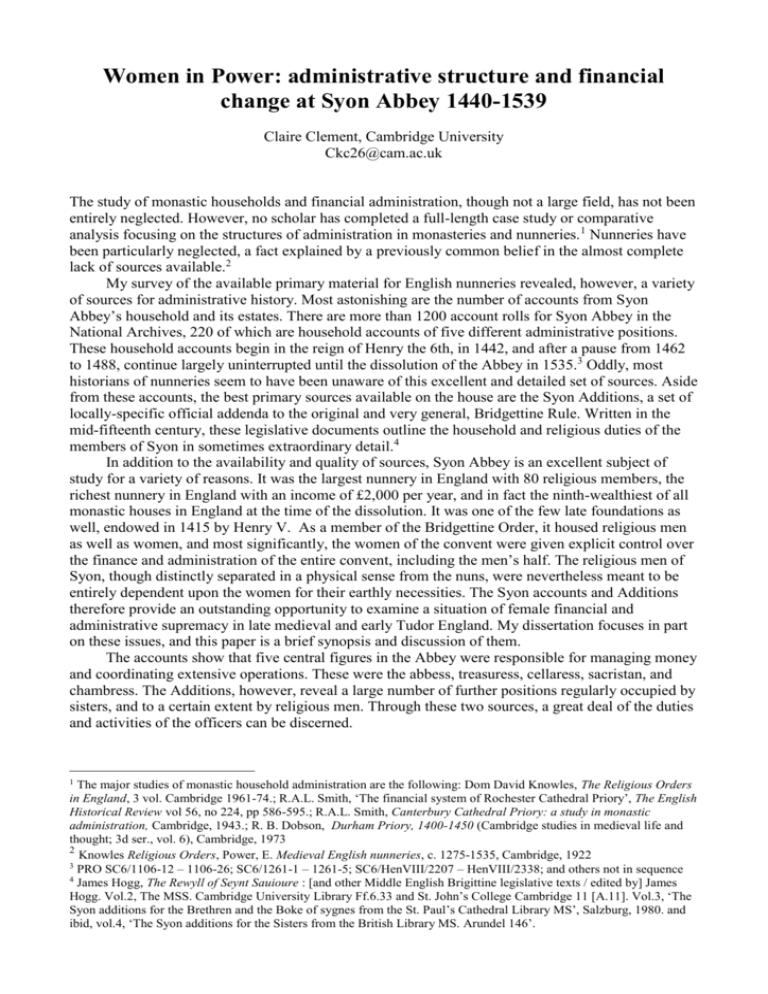

Women in Power: administrative structure and financial change at Syon Abbey 1440-1539 Claire Clement, Cambridge University Ckc26@cam.ac.uk The study of monastic households and financial administration, though not a large field, has not been entirely neglected. However, no scholar has completed a full-length case study or comparative analysis focusing on the structures of administration in monasteries and nunneries. 1 Nunneries have been particularly neglected, a fact explained by a previously common belief in the almost complete lack of sources available.2 My survey of the available primary material for English nunneries revealed, however, a variety of sources for administrative history. Most astonishing are the number of accounts from Syon Abbey’s household and its estates. There are more than 1200 account rolls for Syon Abbey in the National Archives, 220 of which are household accounts of five different administrative positions. These household accounts begin in the reign of Henry the 6th, in 1442, and after a pause from 1462 to 1488, continue largely uninterrupted until the dissolution of the Abbey in 1535.3 Oddly, most historians of nunneries seem to have been unaware of this excellent and detailed set of sources. Aside from these accounts, the best primary sources available on the house are the Syon Additions, a set of locally-specific official addenda to the original and very general, Bridgettine Rule. Written in the mid-fifteenth century, these legislative documents outline the household and religious duties of the members of Syon in sometimes extraordinary detail.4 In addition to the availability and quality of sources, Syon Abbey is an excellent subject of study for a variety of reasons. It was the largest nunnery in England with 80 religious members, the richest nunnery in England with an income of £2,000 per year, and in fact the ninth-wealthiest of all monastic houses in England at the time of the dissolution. It was one of the few late foundations as well, endowed in 1415 by Henry V. As a member of the Bridgettine Order, it housed religious men as well as women, and most significantly, the women of the convent were given explicit control over the finance and administration of the entire convent, including the men’s half. The religious men of Syon, though distinctly separated in a physical sense from the nuns, were nevertheless meant to be entirely dependent upon the women for their earthly necessities. The Syon accounts and Additions therefore provide an outstanding opportunity to examine a situation of female financial and administrative supremacy in late medieval and early Tudor England. My dissertation focuses in part on these issues, and this paper is a brief synopsis and discussion of them. The accounts show that five central figures in the Abbey were responsible for managing money and coordinating extensive operations. These were the abbess, treasuress, cellaress, sacristan, and chambress. The Additions, however, reveal a large number of further positions regularly occupied by sisters, and to a certain extent by religious men. Through these two sources, a great deal of the duties and activities of the officers can be discerned. 1 The major studies of monastic household administration are the following: Dom David Knowles, The Religious Orders in England, 3 vol. Cambridge 1961-74.; R.A.L. Smith, ‘The financial system of Rochester Cathedral Priory’, The English Historical Review vol 56, no 224, pp 586-595.; R.A.L. Smith, Canterbury Cathedral Priory: a study in monastic administration, Cambridge, 1943.; R. B. Dobson, Durham Priory, 1400-1450 (Cambridge studies in medieval life and thought; 3d ser., vol. 6), Cambridge, 1973 2 Knowles Religious Orders, Power, E. Medieval English nunneries, c. 1275-1535, Cambridge, 1922 3 PRO SC6/1106-12 – 1106-26; SC6/1261-1 – 1261-5; SC6/HenVIII/2207 – HenVIII/2338; and others not in sequence 4 James Hogg, The Rewyll of Seynt Sauioure : [and other Middle English Brigittine legislative texts / edited by] James Hogg. Vol.2, The MSS. Cambridge University Library Ff.6.33 and St. John’s College Cambridge 11 [A.11]. Vol.3, ‘The Syon additions for the Brethren and the Boke of sygnes from the St. Paul’s Cathedral Library MS’, Salzburg, 1980. and ibid, vol.4, ‘The Syon additions for the Sisters from the British Library MS. Arundel 146’. As Figure 1 shows, the organizational structure of Syon Abbey was extensive and hierarchical. This figure shows only the main accounting officers and their primary subordinates. However, the additions refer also to many more minor positions of responsibility in the enclosure of Syon, including keepers of doors, grates, and infirmaries. These positions tended to be mirrored by similar positions on the men’s side of the monastery. It is estimated that around thirty five out of the sixty sisters – or 58 per cent - held an office at a time.5 A similar percentage is likely on the brothers’ side. The abbess of Syon was ultimately responsible for the entire administration of the abbey. She was elected solely by the sisters, appointed all officers other than the master confessor on the men’s side, and could fire them at will. The abbess had a separate income from Syon’s treasuress, though not as large, and had distinct financial responsibilities. Her 1512 income of £311, including both rents and offerings at shrines, was used mainly for building and repair work, which constituted her major financial responsibilities. The master confessor was elected by both the sisters and brothers. He reported to the abbess and was responsible for the oversight of conduct and duties on the male side of the monastery. For this, he had the help of several officials, taken from the ranks of the priests, deacons and lay brothers who composed the male side of Syon Abbey. These officials included an infirmarer, cantor, sacristan, and butler, among many minor officers. Oddly, there are no remaining accounts of the master confessor or any of his subordinates. At first this seems in keeping with the Bridgettine Rule, which states that the men’s side of the abbey should be fully dependent on the women for their practical needs and provisioning. But very rarely do any provisions for the men appear in the accounts of the female obedientiaries, which suggests that the men obtained goods through other means – perhaps through their own separate income and provisioning system. It is also possible that Ulla Sander Olsen, ‘Work and Work Ethics in the Nunnery of Syon Abbey in the Fifteenth Century’ The Medieval Mystical Tradition in England: Exeter Symposium V Exeter, 1992. p 134 5 their needs were indeed provided by the cellaress, but it was not deemed necessary to highlight the amounts allocated to them. If their provisions were lumped together in the final cellaress’s accounts with the general provisions of the abbey, then the lack of mention is understandable. One of the few pieces of evidence in the accounts about Syon’s men does indicate, however, that the master confessor, at least, had income which he was free to allocate to others, though the passage suggests that his money may have come from the treasuress initially.6 Another indicates that the sacristan on the men’s side of the Abbey was given money ‘for a year’ by the female sacristan.7 These items indicate that the finance of the male side of Syon Abbey was similar to that of the lesser accounting officials of the female side – who had no income separate from the treasuress, but had freedom of purchasing. The treasuress was charged with keeping track of all coin and property of the monastery. She had a treasury house, in which was kept a great chest filled with gold and silver coins. An intricate system of key-holding and transfer of authority was put in place to reduce the possibility of corruption and collusion regarding abbey finances. Also in the treasury house, and therefore in the care of the treasuress, were all of the accounts, receipts and other financial documents of the Abbey and its holdings. In keeping with her main duties, the treasuress was the main recipient and distributor of funding in the abbey. Her income source was simple but large – money receipts from rent collectors and bailiffs sent to each of her 35 properties in counties as far as Cornwall, and as near as Isleworth manor. In 1512, a typical year in Tudor Syon, rents received by the treasuress from her estates amounted to £1,482. (Figure 2) The bulk of this money was transferred to the cellaress – a total of £1,133. In addition, the treasuress gave money to the chambress and sacristan and paid for various necessities such as doctors, lawyers and spices for festivals. The cellaress had perhaps the most complicated set of tasks in the monastery. In addition to purchasing food and drink for religious of both sides of the monastery, she was also charged with supervising the vast external enterprise of food and drink manufacturing which sustained the abbey. 6 7 PRO SC6/HenVII/1728 PRO SC6/HenVII/1718 The list of her areas of influence is long. With the help of her sub-cellaress and butler, she managed a bakehouse, brewhouse, kitchen, buttery, pantry, cellar, frater, parlor, and the food for the infirmary, as well as any other place of eating, both within and outside the household, for both residents and strangers. She was also charged with supervising, feeding, clothing, and paying all outward servants of the household, and was responsible for the management of the home farm and the nearby dairy farm. Though the treasuress had the largest cash flow at Syon Abbey, the cellaress certainly had the most complicated. Figure 3 is an attempt to represent this graphically. The central feature of the cellaress’s finances is that they were divided into the household account and the foreign account, each obtaining revenue from different sources and each focusing on different expenses. The household account was the simplest and recorded more money than the other. All income in the household account of the cellaress was received from the treasuress – a total of £1,059 in 1512. The greatest sum was spent on food – a category divided into Purveyances (grains, live animals and other food) and Diet (dairy products and fresh fish), which together come to £907. The next greatest expenses were livery and wages, which each cost a substantial £49 in 1512. Unlike the household account just discussed, the cellaress’s foreign account is complicated more by its income than its expenses. There were four types of income. The sale of wool, hides and candles was the most substantial at £49, which demonstrates the continued importance of the home farm to the monastery’s economy. The income from Isleworth Dairy added £32 to the agricultural income of the cellaress. Aside from the minor income of £11 from small tracts of land let out for pasture, and occasional grants from the abbess, the final foreign source of income for the cellaress was derived from the boarding of visitors – especially of devout laypeople wishing to live near the monastery. Compared with the income in the foreign accounts, the expenses are fairly straightforward. Sixteen pounds was spent on various necessary expenses. The greatest cost, however, was the salt store of dried and pickled fish and various spices, at a total of £56 together. Such is the picture of Syon’s administrative and financial structure in the Tudor era - three prominent economic units with separate income elements and separate expenditure specialties. But Syon’s original financial structure seems to have been somewhat different. Though the majority of the existing Syon accounts are from a variety of officers during the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII, the early accounts beginning in the 21st year of the reign of Henry VI, in 1442, and extending until the first year of Edward IV in 1461, are excellent sources as well. The most obvious difference between these early accounts and the later ones is that those of the fifteenth century include only cellaress’s accounts. At first, this was disappointing and suggested that only a part of Syon’s economy of the time would be visible as a result. Examination of the accounts fortunately proved otherwise. Unlike in Tudor Syon’s financial structure, in which each officer dealing with money accounted separately and in which all transfers of money from one officer to another were itemized, in the early accounts, the income and expenses of each officer are entered into the cellaress’s accounts. Alongside receipts by the cellaress from the sale of wool and skins, appear receipts in various forms from the treasuress. One item makes it clear that money is being given by the treasuress directly to the cellaress, for the cellaress’s expenses. But other lines claim an income, ‘received from the same treasuress by the hand of the chambress’, or by the hand of the sacristan. There is even one saying, ‘Received from the same treasuress against payment of diverse regular expenses by the same treasuress’. Meanwhile, in the expenses section of the accounts, expenses of the chambress, sacristan, and treasuress are itemized, alongside the more extensive and detailed list of cellaress expenses. It is therefore clear that the accounts of the many officers were being subsumed into one overarching account created by the cellaress. This system makes it possible to gain an almost complete picture of the finances of the abbey in 20 years of the mid fifteenth century. There are a few things missing, however, which make full comparison with the Tudor accounts difficult. Most importantly, the early accounts include no information about the abbess’s income and expenses. They also do not divulge details regarding the nature of the treasuress’s income. It is impossible to determine how much was from rent, how much in kind, and how much from other sources, if any. The accounts do, however, have enough detail to determine expenses, and fortunately use the same categories of expenses as the later accounts, making comparison possible. A major issue in the administration of Syon Abbey is the role of lay staff and councilors versus that of the monastic officials. Particularly interesting and important is the extent to which Syon’s female officials could manage such vast enterprises from within the enclosure. A key mechanism was no doubt the use of Syon’s household stewards and its extensive and varied hierarchy of substewards, receivers and bailiffs. Though male monasteries of the late Middle Ages tended to use monk-wardens for supervision of estates, Syon Abbey seems to have used a system similar to that of medieval lay households.8 The later accounts and the early both mention ‘stewards of the household’. There were also a chief steward, general receiver and auditor at the time of the Dissolution.9 Both account series mention a bailiff of the demesne of Isleworth, and the Tudor accounts have rentcollectors as well. Though the issue of lay staff/nun relations touches on all the monastic officials, the position of cellaress is an ideal case study. How did she, who was expected to coordinate the efforts of a large lay staff engaged in a variety of disparate enterprises, manage to do this from within the enclosure, with a minimum of secular contact? The steward of the household would obviously have been of great help to the cellaress. Her accounts also show that the understeward and ‘clerk of the kitchens’ were sent on long provisioning journeys.10 It is however unclear from the sources whether the cellaress made most of the decisions herself, or if she mainly acted as general overseer and nominal 8 See for households: C.M. Woolgar The great household in late medieval England, London 1999. For male monasteries, see Smith, ‘Rochester’. Power, Nunneries, p 99, claims Syon’s system of lay officials was the usual system for nunneries. That this system was very similar to that of lay households is understandable – nuns couldn’t manage and oversee their estates personally, but lay landowners most often would rather spend their time doing other things. 9 Valor ecclesiasticus temp. Henrici VIII : auctoritate regia institutus ; J. Caley, and J. Hunter (eds.) (6 vols) London,1810-34. vol 6. 10 PRO SC6/HenVIII/2283 head of an organization managed in truth and fact by the steward who could maintain personal contact and supervision with a variety of lay employees. However, the sometimes feisty and independent disposition of the Syon nuns in political and legal matters suggests that these women held enough personal power and pride to demand professional power and pride of place in important decisions.11 It is likely that they delegated routine decisions only. This centralized power would of course have required more constant communication with outside lay staff to coordinate decisions and implementation. Ideally, the nuns were to have as little contact with seculars as possible, but provision was made for speaking with seculars for official reasons, but at the Abbey through windows or grates. There is also evidence, though, that the nuns did leave the enclosure on occasion. One occurrence was for the gathering of assigned wine from the King’s men at Bishop’s Lynn, probably in 1452.12 Another was journeys of female Syon officials to London for purchasing in the year 1536 – once by the cellaress, and three times by the chambress to buy cloth.13 Unfortunately, both of these sources are suspect, leaving the true mobility of the nuns unknown. It is clear in any case, though, that the Syon administrative nuns were highly capable. Most who attained high office could read Latin, and came from backgrounds in which they would have learned the arts of household management.14 Many were also of high birth and accustomed to the associated power.15 It would be surprising if this knowledge and background didn’t translate into proactive managerial actions by the female obedientiaries of Syon. This paper has briefly demonstrated the unique opportunities and limitations faced by the managerial women of Syon Abbey. The evidence indicates that on the whole the priests and nuns did not adhere strictly to the Rule and Additions regarding finance, provisioning, and even enclosure, but preferred, rather, to make money directly available to those officers on the men’s side who needed it, and thereby free them from complete dependence on the ‘wheel’ in the wall through which the women could pass provisions. They preferred as well, it seems, to allow at least some of the high female officials to leave the enclosure to pursue official business – perhaps to make provisioning more efficient. But since Syon was always considered strictly observant, we can conclude that at this dual monastery, with all of its challenges, a happy balance was struck between ideal and practicality, between the life of the world, and the life of God.16 11 George James Aungier. The History and Antiquities of Syon Monastery. London, 1840, pg 88. and Johnson, F. R. ‘Syon Abbey’ in Victoria History of the Counties, Middlesex, vol 1. 1969, pg 182. 12 Sir William Dugdale Monasticon Anglicanum : a history of the abbies and other monasteries, hospitals, frieries, and cathedral and collegiate churches, with their dependencies in England and Wales 6 vol. ed John Caley, Henry Ellis and Bulkeley Bandinel London, 1817-1830, vol vi pt 1 p 31 NE. There is some uncertainty about the date. 13 Power, Nunneries pg 368. But she gives no source. It is impossible to double check this. 14 Virginia R Bainbridge ‘The Bridgettines and Major Trends in Religious Devotion c 1400-1600: with Reference to Syon Abbey, Mariatroon and Marienbaum’, Birgittiana, 19. 2005, 234-5, 15 Aungier pg 80. Edward IV’s sister Anne was a Syon nun and later prioress, and their mother Cecily was a close supporter and friend of the abbey. 16 G.W. Bernard, The King’s Reformation: Henry VIII and the Remaking of the English Church by GW Bernard, London 2005, 167