tan1 - University of Buckingham

Journal of Language and Learning Vol. 1 No. 2 2003 ISSN 1740 - 4983

Language Corpora for Language Teachers

Melinda Tan

Assumption University, Bangkok, Thailand

iele.au.edu

Abstract

This paper tries to put forward the case for the use of language corpora in language pedagogy. It highlights some of the problems in language description as a result of the use of intuition rather than objective data. The paper ends with some suggestions of classroom activities based on the use of English corpora.

The main advantage of using language corpora especially in EFL classrooms is that corpora can function as useful sources of information for non-native English teachers and students. Furthermore, through the use of corpus data, students can develop a heightened sensitivity to patterns of authentic language use in native

English environments.

1.0 Limitations in the Use of Intuition in Language Teaching

Foreign language teaching has always relied on the intuitive perceptions of what coursebook designers themselves know about the nature and structure of language.

However, there are three dangers of relying on intuition when designing a coursebook:

1) Contexts created for oral practice give the impression of problem-free communication among speakers

2) Examples given in coursebooks are viewed as authentic language communication in a native speaker environment.

3) Grammar and vocabulary are perceived as separate areas of language teaching

Contexts created for oral practice give the impression of problem-free communication among speakers and examples given in coursebooks are viewed as authentic language communication in a native speaker environment.

2.0 Real Language Communication

In language coursebooks, there is the impression that interaction between speakers progress smoothly and is problem-free. There is the assumption that speakers co-

98

Journal of Language and Learning Vol. 1 No. 2 2003 ISSN 1740 - 4983 operate with each other politely, the conversation is neat, tidy and predictable.

Utterances are almost as complete sentences, no-one interrupts anyone else or speaks at the same time as anyone else. Questions and answers are sequenced as if in a tightly rigid structure of a classroom. According to Carter (1998: 47), the language of some coursebooks represent a ‘can-do’ society.

However, interaction as we know it does not proceed in this manner. Interaction between speakers is messy, untidy and sentences are usually ungrammatical when compared to standard English. A comparison of an ‘unreal’ textbook interaction where the language is scripted and an example of ‘real’ world language interaction is given below.

Text 1:

[At a local café]

Tom: Hey, Helen! Karini!

Helen: Oh, hello Tom.

Tom: I can’t understand this menu. What’s an aubergine ?

Helen: Er, it’s a kind of vegetable. It’s long and round, and purple. In America you

call it an Eggplant.

Tom: Eggplant ? Oh no, I don’t like eggplant. What’s a ploughman’s lunch ?

Karini: It’s got a slice of bread, a piece of cheese, and some lettuce…It’s sort of

salad.

Tom: Salad ? That’s rabbit food! Isn’t there any real food ? What’s a black

pudding – an ice cream ?

Helen: No, it’s a kind of sausage, Tom. It’s made of blood…

Tom: Oh, that’s gross!

Helen: Come on, I’ll show you the local café.

(Elsworth, Rose and Date, Go for English!

Book 5, Unit 6) (1997)

Text 2

Transcript (from Carter and McCarthy (1997) - data is based on the CANCODE corpus)

1 <S01> Does anyone want a chocolate bar or anything ?

2 <S01> Oh yeah yes please

99

Journal of Language and Learning Vol. 1 No. 2 2003 ISSN 1740 - 4983

3 <S02> Yes please

4 <S02> [laughs]

5 <S03> [laughs]

6 <S01> You can have either a Mars Bar, Kit-Kat or erm cherry Bakewell

7 <S03> Oh erm it’s a toss-up between [<S02>[laughs]]the cherry Bakewell and the

Mars Bar isn’t it ?

8 <S01> Well shall I bring some in then cos you might want another one cos I don’t

want them all, I’m gonna be

9 <S03> Miss paranoid about weight aren’t you ?

10<S01> Yes but you know

11<S03> You’re not fat Mand

12<S01> I will be if I’m not careful

13<S02> Oh God

14<S01> I ate almost a whole jar of raisins this weekend [<S02><S03>[laugh]]

my mum gave me all these

15<S03> Look at her, look

16<S01> She goes oh [inaudible]

17<S03> What was that about, you said about you and your Mum don’t get on

[<S02>[laugh]] I’d say you got on all right with that big wodge of food

there

18<S01> We can relate to chocolate…I think they’re the little ones actually so you can have

one of them and one of them if you like

19<S02> Oh those cherry Bakewells look lovely

20<S03> They do don’t they ?

21<S01> Oh they were…gorgeous…did you say you’d like a cup of tea ?

22<S02> Yes

23<S03> All right then

24<S01> Sound like a right mother don’t I ?

25<S03> You do

26<S02> But they would go smashing with a cup of tea wouldn’t they ?

27<S01> They would yeah

28<S02> Cup of tea and a fag

29<S01> Cup of tea and a fag Misses, we’re gonna have to move the table I think

While the two texts focus on a conversation before ordering food, this is the only similarity between the two. It is clear that Text 2 contains familiar features of real

English spoken discourse such as ellipsis, back-channelling, hesitations

100

Journal of Language and Learning Vol. 1 No. 2 2003 ISSN 1740 - 4983 ungrammatical forms and informal colloquialisms. Utterances are frequently incomplete sentences as a result of interruptions and overlaps in turn taking. One other feature that is apparent in the data contained in Text 2 is that the although the conversation about what kind of food to order, there are rapid topic shifts and recycling within the conversation as new topics are constantly introduced and recycled. These rapid topic shifts lend fluidity to the conversation which makes it natural compared to Text 1 where there are no topic shifts thus forcing the conversation to sound very unnatural and rigid.

It should be acknowledged that with regard to teaching, ‘textbook English’ has the advantage over ‘real’ English, whenever a language teaching point has to take precedence over the reality in dialogue. However, the argument here is that textbook

English does not expose students to real spoken English at all. There is no sense of real interaction in the target language since there is a mismatch between ‘scripted’ language in textbooks and ‘real’ interaction. To overcome this problem of mismatch, one suggestion is for coursebook designers to provide examples of ‘real English’ in textbooks. By this it is meant, giving students the opportunity to observe how textbook English differs from real English, by providing passages of more or less the same content for comparison.

The final criticism that will be raised in this paper regarding the use of intuition in designing coursebooks is the persistence of coursebook designers and even teachers in viewing grammar and vocabulary as separate areas of language teaching. The standard view of language is that it is divided into grammar (structure) and vocabulary (words). However, language learning according to Lewis (1997) and

Pawley and Syder (1983) occurs in multi-word prefabricated chunks such as collocations and fixed expressions. These prefabricated chunks of language are responsible for the native speaker’s ability to convey his meaning through expressions that are grammatical and also nativelike, as well as his ability to produce fluent stretches of connected discourse. The mastery of these prefabricated chunks of language is the foundation of fluency, naturalness, idiomaticity and appropriateness.

Furthermore, results from research by Sinclair (1991) convincingly demonstrate that:

101

Journal of Language and Learning Vol. 1 No. 2 2003 ISSN 1740 - 4983

"…each meaning can be associated with a distinct formal patterning…There is ultimately no distinction between form and meaning…(The) meaning affects the structure and this is… the principle observation of corpus linguistics in the last decade…” (Sinclair, 1991a:

6-7)

Thus, based on psycholinguistic theories of language learning and descriptive evidence from corpus studies, it seems surprising that intuition should still play an important role today in coursebook designs, in matters as important as separating the teaching of grammar and vocabulary.

3.0 Using Language Corpora in Pedagogy

While the arguments presented above have sought to illustrate the disadvantages of relying on intuition for language teaching and learning, the benefits of using descriptive evidence for teaching and learning purposes are now described. More specifically, the use of language corpora as a resource for teaching, planning and learning will be proposed.

Language corpora are actually collections of texts (written and spoken) taken from native speaker environments. An example of a language corpus is the BNC (British

National Corpus) which has a total of 100 million English words taken from the writing and speech samples of native British speakers. Data from corpora are also easily accessible on the internet or available on CD-roms. There are three areas in language teaching which can benefit from the use of corpora:

1) Materials design: as a source to teachers to provide linguistic information for those who are not native speakers of the foreign language and also as a resource for

CALL (Computer Assisted Language Learning).

2) Curriculum design: to provide a source of authentic texts for selecting and sequencing what needs to be taught

3) Classroom methodology: as a resource for data-driven learning and task-based activities.

In countries where English is taught as a foreign language, corpora can be a useful source of information for teachers who are non-native speakers of the language.

Corpora can be used as valuable resources of linguistic reference and for materials

102

Journal of Language and Learning Vol. 1 No. 2 2003 ISSN 1740 - 4983 design. As a start, teachers can collect useful ready-made materials based on corpus data of real English usage from corpus teaching web sites. As a second stage to making their own materials, teachers can make use of simple concordancing packages like WordSmith or MonoConc to select the language items that they find they need to teach based on their learners’ needs as well as what is important to teach, based on frequency information taken from a corpora. The last and most advanced stage of materials development which moves into the realm of curriculum design is that of constructing a learner corpus. The advantage of setting up a learner corpus is that it provides a more detailed picture of a type of language which corresponds most closely to the target language behaviour of school-age non-native learners. Thus, information about one’s non-native learners can be gleaned from a simple analysis of common types of learner errors to more complicated analysis of native-language interference in the influence of the learner’s English. Thus learner corpora can provide a valuable source of information for teachers and coursebook designers on what to teach and how to teach by designing custom-made learning materials or designing their own CALL packages.

Corpora can also be used in language learning, especially with respect to classroom methodology .

While it is acknowledged that communicative teaching focuses on fluency and the negotiation of meaning, it however fails to teach learners develop a sensitivity to patterns in language. By this it is meant that communicative teaching fails to teach learners how to know if a particular meaning of a word is appropriately or accurately used in a context. In order of learners to know this, they have to be sensitive to patterns in language and to know how the meanings of words are dependent very much on repeated patterns of grammatical choice i.e. the grammatical context.

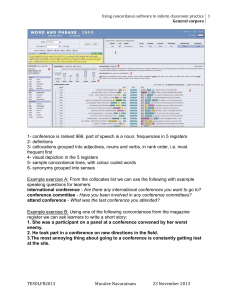

The following activity illustrates how such sensitivity to patterns in language could be developed.

Activity 1: Meaning and Context

103

Journal of Language and Learning Vol. 1 No. 2 2003 ISSN 1740 - 4983

If we study instances of usage, we find that the surrounding words and phrases help a lot in determining the meaning. Consider, for example, the concordance of the word

‘block’ in the data file.

on foot between the administration block and some cells can take up to 25

operations are moves designed to block enemy penetrations.

Fee are variable. In 1985, Block filed 10 million tax returns

The 16 th

Century, salt was used in block form and scrapped off with a knife.

Zulu men for rural areas) and a road block had been set up by young men

Ltd. Could also find itself on the block if Sir James Goldsmith succeeds in

The livery yard. Although the stable block is in darkness, she knows her own

Cross as he led the crod on a three -block march to police headquarters.

Next to the main assembly block of the shipyard in the Baltic port

Deep pockets, and setting it upon a block of stone between himself and the

The antagnists fasten onto and block off the receptors so that the

He would chase one leaf half a block or more with his blower,

Effectively took itself off the block yesterday and announced a sweeping

Off ALL THREE numbers in a single block upi’re a winner.

Another is to go to extremes to block your neighbours out of your life

And circumstances that appear to block your path. There is a certain

Nationalists today said they will block Yugoslavia’s border crossings with

Questions:

1. Read each example in turn and work our its sense. Do not use a dictionary, but

make notes on the meaning.

2. Group the meanings together wherever you can. Do you recognise any phrases,

phrasal verbs, idiomatic constructions or the like among the twelve ?

3) Pick out the instances with a physical meaning. Study the four of five words on

either side of block and make notes on any repeated patterns of grammar or

vocabulary choice.

The activity is corpus-driven in the sense that the learning comes from analysis of corpus data. It uses a discovery-based interaction with the language, where learners are required to answer questions aimed solely at developing skills such as observation, hypothesis and analysis. These skills focus on developing an increased sensitivity to language use and are skills which are rarely or hardly ever developed in communicative teaching.

4.0 Conclusion

104

Journal of Language and Learning Vol. 1 No. 2 2003 ISSN 1740 - 4983

In conclusion, the benefits of using descriptive evidence in language teaching and learning rather than to rely on intuition need to be emphasised. With increased access to technology and its advances, language corpora will have a growing importance in language teaching. The advantages are countless and the illustrations given in this paper are but a simple testimony of the interest and experience which have resulted from a convergence of language teaching and language research from corpus-based methods.

About the Author

Dr Tan teaches within the Institute for English Language Education (IELE) at

Assumption University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Email: Melinda.Tan@iele.au.edu

References

Carter, R. (1998) “Orders of reality: CANCODE, communication and culture” in

ELT

Journal , vol. 52 n.1, pp 43-56.

Carter, R. and McCarthy, M. (1997) Exploring Spoken English , Cambridge: CUP.

Pawley, A. & Syder, F.H. (1983) “Two puzzles for linguistic theory: nativelike selection and nativelike fluency” in Richards, J.C. and Schmidt, R.W. (eds.)

Language and Communication , Harlow: Longman.

Sinclair, J. (1991) Corpus, Concordance, Collocation, Oxford: OUP.

Lewis, M. (1993) The Lexical Approach , Hove: Language Teaching Publications.

Lewis, M. (1997) Implmenting the Lexical Approach, Hove: Language Teaching

Publications.

Wichmann, A. Fligelstone, S., McEnery, T. and Knowles, G. (eds) (1997) Teaching and Language Corpora, London: Longman.

105