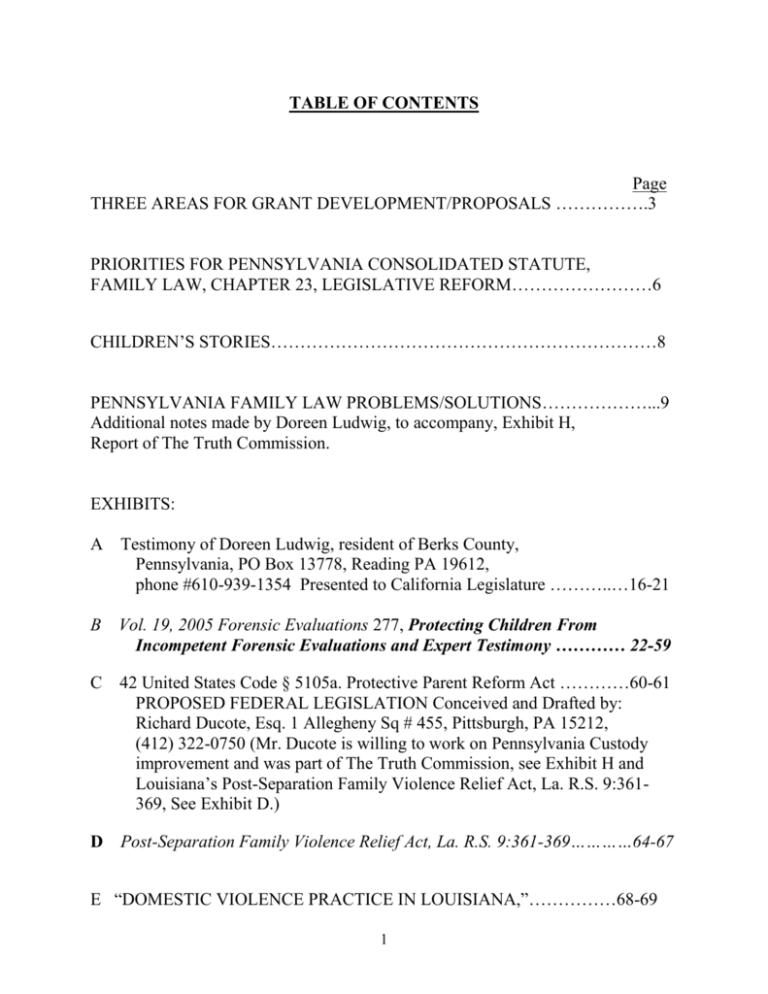

The Louisiana legislature passed Post

advertisement