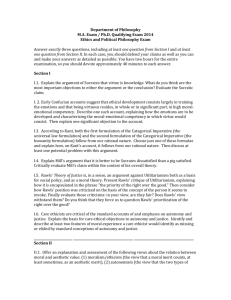

The Philosophic Foundations of Human Rights

advertisement