..the Mughal dynasty The citadels of glory the prince is destined to

advertisement

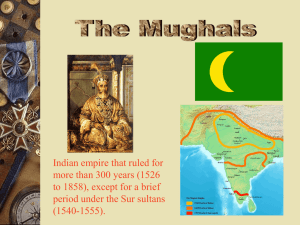

the Mughal dynasty ... The citadels of glory the prince is destined to inherit... download to listen: 28k, 56k, ISDN* Shah Jahan's ancestry was no ordinary birthright. He was descended from the merciless Mongol invader, Ghengis Khan, on his mother's side and on his father's side the infamous Amir Timur, known as Tamberlane to the Western world. Scarcely less notorious for his barbarism than the Mongols, the Turkish ruler had invaded Hindustan in 1398, massacred its inhabitants and brought back riches beyond his wildest dreams: trays of gold and carved ivory and mounds of jewels – rubies, pearls, emeralds, turquoise, topaz and cat's eye, and diamonds said to be so valuable they might have fed the world for a day. By the 15th century, the wealthy Persian empire stretched thousands of miles, from eastern Syria to points near China, and the nomadic invaders who had caused such widespread slaughter and destruction throughout Central Asia had become devout Muslims and fervent patrons of scholarship and the arts. In Timur's fabled city of Samarkand, academics and intellectuals taught great literature, poetry, languages, history and painting at the many colleges; artists thrived and merchants filled the bazaars with luxurious treasure from around the world. Timur's subjects led lives of great refinement, and the Persian empire was counted among the most civilized in the world. According to Timurid custom, when the head of a clan died, his lands were parceled out among the sons. But by the early 1500s, struggles for succession had divided the mighty Central Asian empire (what is now Uzbekistan) into small warring kingdoms. One young prince, driven from his rightful kingdom and drawn by the memory of his ancestor's success, looked south into Hindustan for a dominion of his own. The land was not well defended, and Babur the Tiger soon conquered what is now northern India. Though the opposing forces had ten times the troops, Babur was more skilled in the arts of war. In 1526, he defeated the Afghani Muslim ruler in a brutal battle on the plains of Panipat and put an end to the 300-year-old Sultanate of Delhi. "Babur was the first in a series of emperors of north India called Mughals," says Beach. "They were men of enormous physical activity, especially the first three emperors. They were out defeating rebels, building their power, building up the empire, establishing the wealth of the dynasty. (The term "Mughal" is derived from "Mongol," although Babur preferred to think of himself as Timurid.) The Timurid rulers brandished the sword and the pen with equal ability and were themselves accomplished poets of the loftiest form. It is from their memoirs that we have come to know of their illustrious history. Prince Kurrham loved to hear the stories of his famous ancestors. His favorite books were the Baburnama (Memoirs of Babur), the Akbarnama (Memoirs of Akbar) and volumes of poetry. Babur's son, Humayun, became the second Mughal emperor. A gentle man who preferred aesthetics to battle, he almost lost the new dominion to rebellious local rulers. But the kingdom survived and passed into the capable hands of his son, and Babur's grandson, Akbar the Great. Third in the line of Mughal rulers, Akbar defeated the Afghans and firmly established Mughal supremacy in northern India, bringing the empire to the height of its power and wealth. He was the Grand Mughal, renowned even in the most distant corners of the civilized world. Having inherited a stable and prosperous empire, Shah Jahan's father, Jahangir, pursued his delight in the more refined art of miniature painting, bringing about a golden age of painting at the Mughal court. The Mughal emperors used the arts and architecture to express their imperial prestige. "This was the first time you had wealth at that level interested in commissioning the arts, and in particular, the arts embodying and confirming wealth," says Milo Beach. "And I think nowhere was that more true than in India, simply because of the tremendous resources of the country, the access to jewels, the access to a kind of internationalism, so many people passing through the court. The idea of 'the grand Mughal' spawned all kinds of myths of unfathomable, unimaginable wealth that Europeans associated with the east. They gave the term 'mogul' to the English world. A mogul is someone of tremendous wealth and tremendous power. Hollywood moguls. Wall Street moguls. They set the standard which in many ways people have been trying to achieve ever since." Babur the Tiger Like his Persian ancestors, Babur was as much a scholar and poet as a soldier. When the dust settled on the plains of Paniput in 1526, Babur was dismayed to see the spoils of his victory: "Hindustan is a place of little charm," he wrote in his memoirs. "There are no refined arts or other delights of urbane society, no poetic talent or understanding... The arts and crafts have no harmony or symmetry... There are no good horses, meat, grapes, melons or other fruit... Hindustan is a strange country; compared to ours, it is another world. And the heat and dust are unbearable." (from the Baburnama) Babur had brought with him to Hindustan a taste for luxury and culture, the influences of his Islamic faith and a love of the order,symmetry and formality of the gardens of his native land. Fresh from a country of verdant landscapes, he noted in his journal: "One of the chief faults of Hindustan is that there is no running water. The whole country appeared so ugly and desolate that I passed the river thoroughly disgusted... On the other hand, one nice aspect of Hindustan is that it is a large country with lots of gold and jewels..." Babur chose not to murder and loot as his famed ancestor had done 127 years earlier; instead, he stayed and founded a dynasty. In 1526, he laid out a garden on the banks of the Jamuna River at Agra to rival any in Persia, and endowed his successors with a small kingdom and a passion for beauty. Akbar the Great During Akbar's reign, the Mughal empire tripled in size and wealth. Akbar had created a powerful army and instituted effective political and social reforms. By abolishing the sectarian tax on Hindus and appointing them to high civil and military posts, he was the first Muslim ruler to win the trust and loyalty of his Hindu subjects. He had Hindu literature translated, participated in Hindu festivals, and realizing that a stable empire depended on strong alliances with the Rajputs, fierce Hindu warriors, he married a Rajput princess. Akbar was truly an enlightened ruler, a philosopher-king who had a genuine interest in all creeds and doctrines at a time when religious persecution was prevalent throughout Europe and Asia. Understanding that cooperation among all his subjects – Muslims, Hindus, Persians, Central Asians and indigenous Indians – would be in his best interest, he even tried to establish a new religion that encouraged universal tolerance. Akbar was strong-willed, fearless and often cruel, but he was also just and compassionate and had an inquiring mind. He invited holy men, poets, architects and artisans to his court from all over the Islamic world for study and discussion,and he created an astounding library of over 24,000 volumes written in Hindi, Persian, Greek, Latin, Arabic and Kashmiri, staffed by scholars, translators, artists, calligraphers, scribes, bookbinders and readers. Manifesting the ancestral love of the arts on a monumental scale, Akbar filled the landscape with walled cities of royal pleasure and comfort, designed to dazzle the native rajas and advertise the glory of his reign. In the lovely capital city of Agra, Akbar built his remarkable Red Fort beside the Jamuna River. Part fortress, part palace, its construction proceeded at a hectic pace, and in eight years of frenzied building, more than five hundred graceful pavilions and sumptuous residences – adorned with exquisite carvings, lattice and pierced-stone screens,wall paintings, canopied roofs, carved brackets and pilasters – were created within the massive red sandstone walls to accommodate his considerable court. And Agra became the repository for all the wealth and talent of one of the most extensive empires in the medieval world. Taj Mahal: Memorial to Love Long long ago, in a land called Hindustan, reigned a dynasty of Kings as cultured as they were courageous... It isn't that they were without fault – they could be cruel and cunning warriors – but they were also men of exceptionally good taste, and blessed with the bountiful means to express their vision, they built a splendid empire of beauty, knowledge and grace beyond any known before. Now there was one among them, known as "King of the World," whose heart's passion burned like fire, and who built a monument for the sake of love that would capture the imagination of the world... download to listen: 28k, 56k, ISDN* At the age of fifteen, the prince who would be called King of the World met a refined and highborn young girl at a bazaar within the walls of the royal palace in Agra. Court poets celebrated the girl's extraordinary beauty. "The moon," they said, "hid its face in shame before her." For both, it was love at first sight. Five years would pass before the auspicious day chosen for their wedding, and from that moment, they became inseparable companions. Prince Khurram was the fifth son of the Emperor Jahangir, who ruled in the country now known as India in the sixteenth century. Although the prince was not the eldest son, he soon became the favorite. "Gradually as his years increased, so did his excellence," wrote Jahangir. "In art, in reason, in battle, there is no comparison between him and my other children." At his father's command, Prince Khurram led many military campaigns to consolidate the empire, and in honor of his numerous victories, Jahangir granted him the title "Shah Jahan", "King of the World", a tribute never before paid to an as yet uncrowned Mughal king. But when Jahangir's health failed, his sons rivaled for succession to the throne. Ultimately, after years of battle and the deaths of his brothers under suspicious circumstances, Shah Jahan was victorious. In 1628, the King of the World ascended the throne in a ceremony of unrivaled splendor. Beside him stood his queen, his comrade and confidante. He titled her "Mumtaz Mahal", "Chosen One of the Palace", and commissioned for her a luxurious royal residence of glistening white marble. In turn, she gave him tender devotion, wise counsel and children – many children – to insure the continuance of the magnificent Mughal dynasty. The reign of Shah Jahan marked the long summer of Mughal rule, a peaceful era of prosperity and stability. It was also an age of outrageous opulence, and a time when some of the world's largest and most precious gems were being mined from India's soil. According to author and art historian Milo Beach, "Jewels were the main basis of wealth, and there were literally trunks of jewels in the imperial treasury, trunks of emeralds, sapphires, rubies and diamonds. Shah Jahan inherited it all. He had immense wealth and tremendous power and palaces all over the country." The splendor of his court outshone those of his father and grandfather. Inscribed in gold on the arches of his throne were the words, "If there be paradise on earth, it is here." But in this world, there is an ancient tradition: sweet pleasure is not without bitterness to listen: In 1631, in the fourth year of his reign, Shah Jahan set out for Burhanpur with his armies to subdue a rebellion. Even though Mumtaz Mahal was in the ninth month of a pregnancy, she accompanied him as she had done many times before. On a warm evening of April in 1631, the queen gave birth to their fourteenth child, but soon afterwards suffered complications and took a turn for the worse. According to legend, with her dying breath, she secured a promise from her husband on the strength of their love: to build for her a mausoleum more beautiful than any the world had ever seen before. The King cried out with grief, like an ocean raging with storm... He put aside his royal robes and for the whole week afterward, His Majesty did not appear in public, nor transact any affairs of state... From constant weeping he was forced to use spectacles, and his hair turned gray... download to listen: 28k, 56k, ISDN* Shah Jahan grieved for two years. By official opinion, he never again showed enthusiasm for administering the realm. His only solace would be found in the world of art and architecture, and an obsession with perfection that would last his lifetime. Six months after the death of his wife, he laid the foundation for her memorial across the Jamuna River near his palace in Agra... the jewel of India, the far-famed Taj Mahal. Pearly pink at dawn and opalescent by moonlight, Mumtaz Mahal's tomb is so delicately ethereal that it threatens to disappear during Agra's white-heat afternoons. In the center of the mausoleum lie the remains of the Empress. Subdued light filters through the delicate screens surrounding her cenotaph and mullahs chant verses from the Koran. It is here that Shah Jahan came with his children to honor the memory of his beloved wife. Here, at last, he found solace. But Shah Jahan's tranquility was suddenly shattered when his son Aurangzeb assailed the throne. Just as Shah Jahan had conspired against his brothers for Jahangir's empire, so did his own son plot against him. In 1658, Aurangzeb declared himself emperor and imprisoned his father in a tower of the Red Fort in Agra. For Shah Jahan, King of the World, who once commanded the unbounded wealth of an empire, his only consolation would be a view across the Jamuna River to his vision of Paradise. Shah Jahan created his vision of the world, not as it is, but rather as it should be – harmonious, graceful and pure. Inspired by love and shaped to perfection, the Taj Mahal immortalizes one man's love for his wife and the splendor of an era. Let the splendor of the diamond, pearl and ruby vanish like the magic shimmer of the rainbow. Only let this one teardrop, the Taj Mahal, glisten spotlessly bright on the cheek of time... (Poet Rabindranath Tagore) .fall of an empire For the sake of a throne, the purse of the earth was emptied of treasure... * The reign of Mughals from Akbar to Shah Jahan had been an era of relative peace and unrivaled prosperity in India, a time when culture and the arts had flourished, dazzling cities had been constructed, roads for trade and war were built, government was structured, the economy reformed, agriculture promoted, religious tolerance fostered and rebellions scarce. But Shah Jahan's fifth and youngest son, Aurangzeb, had little interest in the arts – he wasn't fond of poetry or music, and as a pious Moslem, painting was too irreligious for his tastes. He also disapproved of his father's lavish lifestyle, accusing him of squandering the treasury on frivolous constructions. When the emperor became seriously ill in 1657, Aurangzeb began a two-year-long maneuvering for power. By 1658, he had eliminated his brothers, declared himself emperor and imprisoned his ailing father. He immediately put an end to the patronage of court artists, and revoked many of the policies of religious tolerance that had been in place since Akbar's reign, hoping to impose orthodox Islam on all of India. A hero to the Muslims, he was an oppressor to the Hindus. Shah Jahan died eight years after Aurangzeb took the throne. Acknowledging the deep love between his parents, Aurangzeb buried his father next to Mumtaz Mahal. "My father entertained a great affection for my mother;" he wrote, "so let his last resting place be close to hers." The emperor's cenotaph, placed to the side of his queen's, is the only apparent imbalance in the entire Taj Mahal complex. Strained by a diminishing treasury and Aurangzeb's rigid governance, anarchy and dissension reigned, and the empire began to crumble. When Aurangzeb died at the age of eighty-nine in 1707, he was buried in a small tomb by the side of a road.