Heritage Language Task Force Report

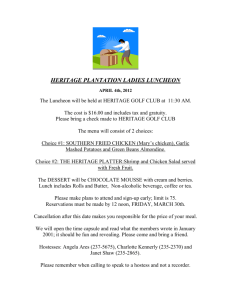

advertisement