Pro

advertisement

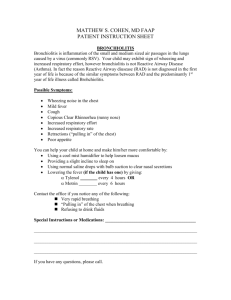

Systemic Corticosteroids Should be Used for Pre-School Children with Virus-Induced Wheezing Miles Weinberger MD Professor of Pediatrics University of Iowa Children’s Hospital Iowa City IA www.uihealthcare.com/allerpulm Reprint requests to: Miles Weinberger MD Pediatric Dept., UIHC 200 Hawkins Drive Iowa City IA 52242 e-mail: lmiles-weinberger@uiowa.edu Phone: 319 356-3485 Fax: 319 353-6217 1 2 Corticosteroids for the Pre-school Age Child with acute Viral Wheeze (a.k.a. intermittent viral respiratory infection induced asthma)1 A recent publication in the New England Journal of Medicine reported that pre-school aged children with wheezing from viral respiratory infections benefitted no more from 10 mg of prednisolone daily than from placebo.2 That led Dr. Andrew Bush, in an accompanying editorial, to conclude that “Prednisolone should be administered to preschoolers (with viralinduced wheezing) only when they are severely ill in the hospital.”3 Pre-schoolers are, in fact, frequently in the hospital with wheezing. Asthma most typically begins in the pre-school age group with the first year of life the most common time for onset of symptoms (Figure 1).4 There is approximately one hospitalization for asthma in a preschooler for every 200 pre-school age children annually in the U.S. (Figure 2).5 The implications of the New England Journal of Medicine publication and Dr. Bush’s recommendation based on that publication is that we have no solution to the endemic problem of pre-school age hospitalizations for asthma. Is that nihilistic view justified? First, we must consider that viral respiratory infections are a major cause of asthma exacerbations at all ages6,7,8,9,10 and appear to be the major risk factor for the large increase in hospital admissions for asthma that occurs every autumn.11 Pre-school age children have a particularly high frequency of viral respiratory infections, with most getting 3-8 infections per year and 10-15% getting 12 or more per year.12 This is the likely explanation for the frequency of asthma hospitalization in the pre-school age group that far exceeds that of older children and adults.5 There is no active debate regarding the lack of value of inhaled corticosteroids for either the treatment or prevention of viral induced wheeze. The use of inhaled 3 corticosteroids for intervention of acute symptoms has been examined in the emergency department and at the onset of an exacerbation at home. Such attempts have been at best marginally successful with some amelioration of symptoms at very high doses but no significant effect on the need for subsequent emergency care, hospitalization, or decisions to use an oral corticosteroid.13 These agents also do not prevent exacerbations of asthma from viral respiratory infections.14,15,16 Nor are there any other currently available therapeutic measure that can, as safe maintenance therapy, prevent viral respiratory infection induced asthma.17 Since viral respiratory infections are the major contributors to acute care requirements for asthma, especially in young children who have an especially high frequency of these common cold viruses, providing effective intervention measures to treat viral respiratory infection induced asthma is critically important in current efforts to stem the endemic tide of asthma morbidity. So let’s examine the effect of systemic corticosteroids administered prior to the hospitalized severely ill patients for whom Dr. Bush feels such treatment should be limited. Several studies over the past 15 years have demonstrated that earlier aggressive use of systemic steroids in children, including pre-school age children, having an acute exacerbation of asthma decreases the likelihood of requiring urgent care and hospitalization.18 Storr et al examined the effect of oral prednisolone in children administered immediately after being hospitalized with acute asthma.19 In a randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial, 67 children received prednisolone and 73 received placebo shortly after admission. Mean age of the children was 5 years. Those less than 5 years old received 30 mg of prednisolone and those 5 or older received 60 mg. At a 5 hour decision time, about 20% of those who received prednisolone could be discharged compared with only about 2% of those who received placebo. 4 Among those not discharged at 5 hours, more rapid improvement and earlier discharge occurred in the prednisolone treated patients than in those in who received placebo. Tal et al examined the value of systemic corticosteroids in children ranging from 0.5 to 5 years of age seen in an emergency room for acute asthma.20 Using 4 mg/kg of IM methylprednisolone or normal saline in a double-blind placebo controlled trial, decision to admit to hospital at 3 hours after medication administration was reduced from over 40% of the 35 given the placebo to about 20% of the 39 given the methylprednisolone. Scarfone et al examined the effect of oral prednisone in children with a mean age of 5 years seen in an emergency room.21 In a randomized double-blind trial, 36 received 2 mg/kg of prednisone and 39 received placebo. At 4 hours, about 50% of the placebo treated children were admitted compared with only about 30% of the prednisone treated children. The differences were substantially larger for a subgroup judged most sick where over 70% of the placebo treated children were admitted compared with less than half of the prednisone treated children. Brunette and colleagues showed that early administration of oral corticosteroids prevented hospitalization in children at high risk for severe acute asthma from viral respiratory infectioninduced asthma.16 He identified a group of 32 children less than 6 years of age, who had an average of 7 hospitalizations in one year for acute viral respiratory infection-induced asthma. During the subsequent year, half were given prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day, at the onset of a viral respiratory infection. This was associated with a 90% reduction in hospitalizations among the treated group, whereas no reduction in hospitalization rate occurred in those who were untreated. Although not a controlled clinical trial, the differences were sufficiently striking that they should not be ignored. 5 Similarly, an outcomes study of 72 pre-school age children (mean age 2.9 years) referred to the Pediatric Allergy and Pulmonary Clinic at the University of Iowa who experienced an intermittent viral respiratory infection induced pattern of asthma had an impressive reduction of urgent care visits and hospitalizations in association with care that involved early use of oral prednisolone at the onset of symptoms requiring more than an occasional need for an albuterol aerosol.22 Our strategy in that study was to provide the families of these young children with an ageappropriate means of giving an inhaled 2 agonist and a supply of oral prednisolone for use when more than an occasional bronchodilator was needed. Specific instructions regarding bronchodilator subresponsiveness were provided. Doses were based on age--10 mg twice daily for infants under one year of age, 20 mg twice daily for toddlers from 1 to 3 years of age, 30 mg twice daily from age 3. Compared with the year prior to referral, our program was associated with a greater than 4-fold reduction, from 90% to only 21%, in the number of patients who required urgent medical care. The total number of urgent care visits decreased from 415 the year prior to entering our program to 29 during the year under our care. Similarly, hospitalizations, which had occurred in 42% of those patients the year before, decreased to less than 6% the subsequent year, with the total number of hospitalizations decreasing from 60 among the 72 patients to only 6. Again, while not a controlled trial, these impressive outcome data support the controlled clinical trials demonstrating the effect of corticosteroids administered prior to hospitalization for severe illness.20,21 How do these data mesh with the controlled clinical trial that impressed Dr. Bush.2,3 The study reported by Panicker, et al, found no difference from placebo when 10 mg of prednisolone 6 were given once daily to preschool age children with viral respiratory infection induced asthma.2 However, their study population improved so rapidly on placebo that any treatment effect would have been obscured, even if doses had been consistent with those that had been effective previously in controlled trials.19,20,21 The same criticism applies to a previous study.23,24 While there is concern that the high frequency of viral respiratory infection-induced asthma in the pre-school child will, at least for periods of time, result in an excessive frequency of oral corticosteroid use, the risks of this effective strategy appears minimal.25 Corticosteroids for the Infant with an Initial Episode of Acute Viral Wheeze (a.k.a. Bronchiolitis) This remains a controversial topic. The use of corticosteroids for bronchiolitis is driven by the similar clinical presentations of bronchiolitis and asthma. A double-blind study of 5 mg/kg methylprednisolone on the first day of hospitalization with half that dose on the second day was published in 1965. Among the 44 patients randomized to the corticosteroid or placebo, no significant differences in outcome were observed.26 Subsequent studies in hospitalized children similarly also concluded there was no effect of systemic corticosteroids on the outcome of bronchiolitis.27,28,29,30,31 However, a meta-analysis that included many of these studies concluded that there was a modest but statistically significant improvement in clinical symptoms, length of stay, and duration of symptoms.32 The mean difference in length of stay or duration of symptoms from the pooled analysis was 0.43 days (CI 0.81-0.05) less among those who received corticosteroids. A subsequent study of 174 children with bronchiolitis who received either a single intramuscular dose of 1 mg/kg of dexamethasone reported significant reductions in mean 7 duration of respiratory distress and length of hospital stay.33 While children up to 2 years old were included in the study, the results were similar in a subgroup analysis of those under 12 months of age. Studies in outpatients who did not require hospitalization when initially seen in the emergency department have suggested that treatment with corticosteroids in that population may be more likely to provide clinical benefit than has been seen in studies limited to inpatients. Significantly lower symptom scores on day 2 were seen following a 2 mg/kg/day of prednisolone given for 5 days who could be discharged from the emergency department.34 A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial among 230 children who received 2 mg/kg/day of prednisolone or placebo for 3 days found the mean duration of respiratory distress to be 2 days in the placebo treated group and only 1 day in the placebo treated group for both the 123 who had to be initially admitted to the hospital and the others who remained as outpatients.35 While that study included patients who had previous wheezing episodes in addition to those for whom their wheezing was a first time event, the authors described similar results for the first time wheezers as for the 2nd time wheezers. A study by Schuh et al demonstrated a 57% reduction (from 44% to 19%) in blinded decisions to hospitalize infants with bronchiolitis seen in the emergency department by 4 hours after administration of 1 mg/kg of dexamethasone or placebo (p=0.039).36 In an attempt to examine the implications of the Schuh study, a large multi-center study by Corneli et al demonstrated no benefit from treating bronchiolitis with the same dose regimen used by Schuh.37 In an editorial related to another positive study,38 I speculated that the conflicting results of studies examining the effect of corticosteroids for bronchiolitis related to timing.39 Early 8 treatment with a high dose of corticosteroid may be effective during an early inflammatory phase of bronchiolitis but is ineffective once that inflammation results in the characteristic dense plugs of cellular debris and strands of fibrin that characterizes the eventual course of bronchiolitis.40 Interestingly, the duration of respiratory distress in the study by Schuh et al was 1.7 + 1.4 days (mean + SD)36 while that of the multi-center study was 3.7 + 2.5 days,37 more than a 2-fold difference. Thus, although the use of systemic corticosteroids for first time wheezing infants remains controversial at best, my previous speculations regarding the timing of corticosteroid administration continues to be worth consideration. Summary While much viral wheezing is mild and self-limited, requiring no intervention, recurrent viral wheezing (i.e., acute exacerbations of viral respiratory infection induced intermittent asthma) is the major cause of hospitalizations in pre-school age children with a prevalence of approximately one hospitalization per 200 U.S. children annually. The value of systemic corticosteroids in decreasing the frequency of hospitalization has been demonstrated in controlled clinical trials, and outcome studies have demonstrated that urgent care and hospitalizations can be prevented by the early use of systemic corticosteroids. For first time wheezing in an infant (i.e., bronchiolitis), the use of systemic corticosteroids is more controversial with conflicting data that may relate to the timing of the corticosteroids. Early use for bronchiolitis may be associated with benefit whereas use later in the course appears to be associated with no benefit. 9 Legends for Figures Figure 1. Annual age- and sex-adjusted incidence of asthma onset in a population-based epidemiologic study in Rochester, Minnesota.4 Figure 2. Hospital discharge rates for asthma as the first-listed, by age group and year – United States, 1980-1999 (data from the National Center for Health Statistics, Center for Disease Control). (Adapted from Akinbami et al)5 10 Figure 1. N u m b e rp e r 1 0 ,0 0 0c h ild re n 7000 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 <1 1-4 Age of onset (years) Girls Boys 5 - 14 11 12 Figure 2. 13 References 1. Weinberger M, Abu-Hasan M. Chapter 55: Asthma in the pre-school child. In Kendig’s Disorders of the Respiratory Tract in Children, 7th edition, Edited by V. Chernick, TF Boat, RW Wilmott, A Bush. 2006, Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 795-809. 2. Panickar J, Lakhanpaul M, Lambert PC, et al. Oral prednisolone for preschool children with acute virus-induced wheezing. N Eng J Med 2009;360:329-38. Bush A. Practice imperfect – treatment for wheezing in preschoolers. N Eng J Med 2009;360:409-10; Yunginger JW, Reed CE, O'Connell EJ, Melton LJ 3d, O'Fallon WM,Silverstein MD. A community-based study of the epidemiology of asthma. Incidence rates, 1964-1983. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;146:888-94. Akinbami LJ, Schoendorf KC. Trends in childhood asthma: prevalence health care utilization, and mortality. Pediatrics 2002;110:315-22. Rakes GP, Arruda E, Ingram JM, Hoover GE, Zambrano JC, Hayden FG, Platts-Mills TA, Heymann PW. Rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus in wheezing children requiring emergency care. IgE and eosinophil analyses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;159:785-90. McIntosh K, Ellis EF, Hoffman LS, Lybass TG, Eller JJ, Fulginiti VA. The association of viral and bacterial respiratory infections with exacerbations of wheezing in young asthmatic children. J Pediatr 1973;82:578-90. Minor TE, Dick EC, DeMeo AN, Ouellette JJ, Cohen M, Reed CE. Viruses as precipitants of asthmatic attacks in children. JAMA 1974;227:292-8. Nicholson KG, Kent J, Ireland DC. Respiratory viruses and exacerbations of asthma in adults. BMJ 1993;307:982-6. Johnston SL, Pattemore PK, Sanderson G, Smith S, Lampe F, Josephs, L, Symington P, O’Toole S, Myint SH, Tyrrell AJ, Holgate ST. Community study of role of viral infections in exacerbations of asthma in 9-11 year old children. BMJ 1995;310:1225-29. Dales RE, Schweitzer I, Toogood JH, Drouin M, Yang W, Dolovich J, Boulet J. Respiratory infections and the autumn increase in asthma morbidity. Eur Respir J 1996; 9:72-7. Rosenstein N, Phillips WR, Gerber MA, Marcy SM, Schwartz B, and Dowell SF. The Common Cold – Principles of Judicious Use of Antimicrobial Agents. Pediatrics 1998; 101:181-4. Hendeles L, Sherman J. Are inhaled corticosteroids effective for acute exacerbations of asthma in children? J Pediatr 2003;142:S26-33. Wilson N, Sloper K, Silverman M. Effect of continuous treatment with topical corticosteroid on episodic viral wheezing in preschool children. Arch Dis Child 1995;72:317-20. Stick SM, Burton PR, Clough JB, Cox M, LeSouef PN, Sly PD. The effects of inhaled beclomethasone dipropionate on lung function and histamine responsiveness in recurrently wheezy infants. Arch Dis Child 1995;73:327-32. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 14 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. Doull IJ, Lampe FC, Smith S, Schreiber J, Freezer NJ, Holgate ST. Effect of inhaled corticosteroids on episodes of wheezing associated with viral infection in school age children: randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ 1997;315:858-62. Doull IJ. Limitations of maintenance therapy for viral respiratory infection-induced asthma. J Pediatr 2003;142:S21-5 Weinberger M. Treatment strategies for viral respiratory infection induced asthma. J Pediatr 2003;142(Supplement): S34-9. Storr J, Barrell E, Barry W, Lenney W, Hatcher G. Effect of a single oral dose of prednisolone in acute childhood asthma. Lancet 1987;1:879-82. Tal A, Levy N, Bearman JE. Methylprednisolone therapy for acute asthma in infants and toddlers: a controlled clinical trial. Pediatrics 1990;86:350-6. Scarfone RJ, Fuchs SM, Nager AL, Shane SA. Controlled trial of oral prednisone in the emergency department treatment of children with acute asthma. Pediatrics 1993;92:5138. Najada A, Abu-Hasan M, Weinberger M. Outcome of Asthma in Children and Adolescents at a Specialty Based Care Program. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2001;87:335-43. Oonmen A, Lambert PC, Grigg J. Efficacy of a short course of parent-initiated oral prednisolone for viral wheeze in children aged 1-5 years: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003; 362:1433-38. Weinberger M, Ahrens R. Oral prednisolone for viral wheeze in young children. Lancet 2004;363:330-1. Ducharme FM, Chabot G, Polychronakos C, Glorieux F, Mazer B. Safety profile of frequent short courses of oral glucocorticoids in acute pediatric asthma: impact on bone metabolism, bone density, and adrenal function.. Pediatrics 2003;111:376-83. Dabbous IA, Tkachyk JS, Stamm SJ. A couble blind study on the effects of corticosteroids in the treatment of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 1966;37:477-84. Van Woensel JBM, Wolfs RFW, van Aalderen WMC, Brand PLP, Kimpen JLL. Randomized double blind placebo controlled trial of prednisolone in children admitted to hospital with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. Thorax 1997;52:634-7. Springer C, Bar-Yishay E, Uwayyed K, Avital A, Vilozni D, Godfrey S. Corticosteroids do not affect the clinical or physiological status of infants with bronchiolitis. Pediatr Pulmonol 1990;9:181-5. Roosevelt G, Sheeehan K, Grupp-Phelan J, Tanz RR, Listernick R. Dexamethasone in bronchiolitis; a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 1996;348:292-5. Klassen TP, Sutcliffe T, Watters LK, Wells GA, Allen UD, LI MM. Dexamethasone in salbutamol-treated inpatients with acute bronchiolitis: a randomized, controlled trial. J Pediatr 1997;130:191-6. De Boeck K, Van der Aa N, Van Lierde S, Corbeel L, Eeckels R. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis: a double-blind desamethasone efficacy study. J Pediatr 1997;131:919-21. Garrison MM, Christakis DA, Harvey E, Cummings P, Davis RL. Systemic corticosteroids in infant bronchiolitis: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2000;105:e44. 15 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. Teeratakulpisarn J, Limwattananon C, Tanupattarachai S, Limwattananon, Teeratakulpisarn S, Kosalaraksa P. Efficacy of dexamethasone injection for acute bronchiolitis in hospitalized children; a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial Pediatr Pulmonol 2007;42:433-39. Goebel J, Estrada B, Quinonez J, Nagji N, Sanford D, Boerth RC. Prednisolone plus albuterol versus albuterol alone in mild to moderate bronchiolitis. Clin Pediatr 2000;39:213-20. Csonka P, Kaila M, Laippala P, Iso-Mustajärvi M, Vesikari T, Ashorn P. Oral prednisolone in the acute management of children age 6 to 35 months with viral respiratory infection-induced lower airway disease: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr 2003;143:725-30. Schuh S, Coates AL, Binnie R, Allin T, Goia C, Corey M, Dick PT. Efficacy of oral dexamethasone in outpatients with acute bronchiolitis. J Pediatr 2002;140:27-32. Corneli HM, Zorc JJ, Majahn P, Shaw KN, Holubkov R, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of dexamethasone for bronchiolitis. N Eng J Med 2007; 357:331-9. Csonka P, Kaila M, Laippala P, Iso-Justajärvi M, Veskikari T, Ashorn P. Oral prednisolone in the acute management of children age 6-35 months with viral respiratory infection induced lower airway disease: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Pediatr 2003;143:725-30. Weinberger M. Corticosteroids for first time young wheezers: current status of the controversy. J Pediatr 2003;143:700-2. Wohl MEB, Chernick V. State of the art: bronchiolitis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1978;118:759-81.