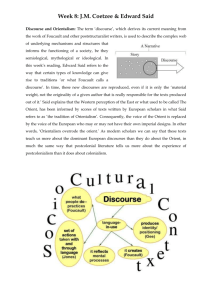

Aesthetic vision on the Orient: The Structure of Vision in three

advertisement