HIST 110

advertisement

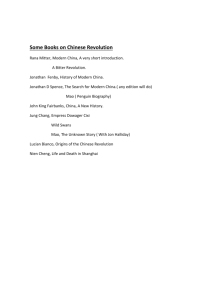

HIST 110.04 The Chinese Revolution of 1949 Fall, 2008 Location: Leighton 202 Time: MW 09:50 –11:00 am & F 09:40 – 10:40 am Instructor: Prof. Seungjoo Yoon syoon@carleton.edu x 4211 Office Hours: M 2:10-4:10 & F 3:00-4:00 and by appointment at Leighton 209 Objective: This seminar explores the origins and developments of the Chinese Revolution of 1949. With the focus on the relationship between Mao Zedong, the main architect of the revolution, and the Chinese people in general, students will learn to exercise the basics of empirical reasoning. Students are invited to immerse themselves in the world of the Chinese whose lives became entangled with the Chairman Mao’s life in one way or another for the most part of the twentieth century. Students are also expected to learn critical methods of historical writing by locating hidden agendas and assumptions of various genres of documents, isolating the use and misuse of historical evidence, and applying historical interpretive skills to their own writings. Thus, by the end of the term, each student would come up with her/his own interpretations of the revolution and their implications for his/her life, now and in the future. I. Course Expectations 1. Pre-Class Caucus Participation & In-Class Presentations: Needless to say, attendance to and active participation in class is always assumed and counted as essential parts of the participation grade. A typical class will be devoted to a discussion based on a critical reading of the assigned readings. The instructor will assume that all the participants will have read the assigned readings, given a critical thought, and be ready to engage in class discussions. Please note that the History 110-04 caucus site is created primarily for pre-class discussion. Each student is expected to complete ALL the reading and screening assignments, frame ONE study question, and post it on the caucus before 8:00 am on the day of each class session. Before coming to class, each student should have read most of the writings of other students and be prepared to carry on the discussion from there. This exercise is MANDATORY. Participants will enjoy at least THREE chances to lead collective or individual presentations on their chosen topics. The presentation formats are wide open even though the instructor will regularly send out broad guidelines for such activities. It can be a small-group presentation, an historical reenactment, a mock debate, or a student-led discussion. Each member of the class must be treated with respect and as an equal individual in the collaborative learning process. 2. Two Review Essays: You are responsible for posting two review essays (2-3 pages, double-spaced, & type-written) on caucus by 4:30 P.M. on the days given below. Answers should be based on a close reading of the assigned texts. In addition to electronic version, the students also need to submit a hard copy of their papers to the instructor’s mailbox. The instructor will evaluate these response papers, provide comments, and hand them back to you in class. 3. A Report based on your research at the Gould Library: You are expected to write a report (2-3 pages) based on your research of the China-related materials at the Special Collections and the Archives (all at the Gould Library’s basement). Its due date is right after the mid-term break. A link to the Special Collections page on the Library web site with contact information, etc.: (http://apps.carleton.edu/campus/library/special_collections/) To request a visit at the Special Collections, you should contact in e-mail the librarians Kristi Wermager (kwermage@carleton.edu 4273) or Terry Kissner (tkissner@carleton.edu 5553). To set up an appointment at the Archives, you should contact Eric Hillermann (ehillema@carleton.edu 4270). 4. Map Exercise: Before the mid-term review, each student is expected to design a historical map based on one (or two) of the common readings and submit it to the instructor’s mailbox. 1 5. Term Paper: The term paper is intended to help the students develop historical writing skills informed by critical analysis. Its maximum length should be eight to ten pages, including bibliography and notes. Any choice of topic is welcome as long as it is related to the course and with the prior consultation with the instructor. Note also that there will be several interim due dates for assignments related to this paper: proposal, outline, bibliography, and oral presentations. The term paper must be done on time and in full. No late papers will be graded. If for some reason any of the students have a problem completing a written assignment, please contact the instructor well ahead of the due date to discuss an alternative arrangement. II. Evaluation: Pre-Class Caucus Participation (Study Questions): 15% In-Class Presentation & Participation: 15 % Two Review Essays: 2 x 10 = 20 % Report on the Library Holdings on the Chinese Revolution: 10 % Map Exercise: 5 % Term Paper (including Proposal & Presentation): 35 % III. Readings: 1. Textbooks to be purchased at the bookstore (Copies are also available on closed reserve at the library): Timothy Cheek, Mao Zedong and China’s Revolutions (Bedford: St. Martin’s, 2002). Jung Chang, Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (New York: Touchstone, 2003). Jonathan Spence, Mao Zedong: A Life (New York: Penguin, 2006). William Hinton, Through a Glass Darkly: American Views of the Chinese Revolution (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2006). Joseph W. Esherick, et al., eds., The Chinese Cultural Revolution as History (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006). Ye Weili & Ma Xiaodong, Growing up in the People’s Republic: Conversations between Two Daughters of China’s Revolution (Palgrave MacMillan, 2005). 2. E-Reserve: Reading marked with an asterisk (*) are available on-line, which is on electronic reserve on the library web. Readings with a sharp mark (#) can be found on other web-sites as indicated below. Students are expected to complete all the reading assignments and post one study question on Caucus before coming to class. 3. References (either on closed reserve or at the reference section at the library): Edwin Pak-Wah Leung, ed., Historical Dictionary of Revolutionary China, 1839-1976 (Greenwood P., 1992). (Ref) DS740.2 .H57 1992 Pei-Kai Cheng & Michael Lestz, The Search for Modern China: A Documentary Collection (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1999). DS753.86 .S33 1999 Howard Boorman, et al., eds., Biographical Dictionary of Republican China, 5 vols. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1967-79). (Ref) DS778.A1 B5 Donald Klein & Anne Clark, eds., Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Communism, 19211965, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971). (Ref) DS778.A1 K55 Stuart Schram, ed., Mao’s Road to Power; 1912-1949 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992). DS778.M3 A25 1992 Stuart Schram, ed., Chairman Mao Talks to the People: Talks and Letters, 1956-1971 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1975). DS778.M3 A2513 1975 Jerome Ch’en, ed., Mao papers, anthology and bibliography (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1970). DS778.M3 A4295 Roderick MacFarquhar, ed., The Secret Speeches of Chairman Mao: From the Hundred Flowers to the Great Leap 2 Forward (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1989). (St.Olaf DS778.M3 A5 1989) Roger Thompson, tr., Mao Zedong: Report from Xunwu (Stanford: Stanford UP, 2000). (Put on close reserve at the library under my History 395: Financing Revolutions) 4. Journals: Journal of Asian Studies (Ann Arbor, Mich., Association for Asian Studies) Modern China (UCLA) China Quarterly (SOAS, U of London, pub. by the Oxford UP) Modern Asian Studies (Cambridge UP) The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs / The China Journal (Australian NU) Pacific Affairs (UBC) Twentieth Century China Chinese Studies in History (Translation of articles from Chinese publications, International Arts and Sciences Press, 1969-2001) (CC Periodical 3rd fl.) Schedule of Class Meetings and Assignments: Week 1: Perspectives on the Chinese Revolution of 1949 Sep. 15 (M) Introduction: Review of course requirements and major themes Why are we here? Why and how do we study Chinese Revolution? What do you think a good historical paper should be? Sep. 17 (W) Perceptions & Problems: Thinking about Chinese Revolution Why do historians often interpret the same historical event differently? Isolate a few salient principles for argumentation in historical writing. Cheek, Introduction, 1-36. Hinton, 11-33. Week 2: Biography Sep. 19 (F) Biography, Autobiography, Hagiography and Psychobiography Compare biographies on Mao with the following questions: How is Mao portrayed in different biographies and why? Which aspects of Mao were stressed or deemphasized in different narratives? What might be the strengths and weaknesses of the following biographies as a historical source? Cheek, Doc. # 11, 183-192; Doc. # 17, 219-225; Spence, 1-45. * Jerome Ch’en, “The Chinese Biographical Method: A Moral and Didactic Tradition,” in Mary Sheridan et al., eds., Lives, 175-9. Week 3: Autobiography I Sep. 22 (M) History and Will What might be a proper way of writing a historical biography? How crucial is it to study Mao Zedong to understand the Chinese Revolution? Would you agree with the author’s views? Why or why not? Spence, 46-178. Sep. 24 (W) Reading Memories How do people choose to remember their lived experiences? What factors motivate people to write an autobiography at a given life juncture? Jung Chang, 1-190 (skim). 3 Sep. 26 (F) Revolution as an experienced past How would you compare Jung Chang to William Hinton in her portrayal of the land reforms in postrevolutionary China? What factors might have led them to different conclusions? In what ways, does an historical analysis differ from personalized accounts? Hinton, 37-59; 241-257. Jung Chang, the rest (skim). Week 4: Autobiography II Sep. 29 (M) Historical inquiry versus the lived past What might be a proper way of reading a memoir? What crucial factors would you consider when you write a review article? # Guobin Yang, “Days of Old are not Puffs of Smoke: Three Hypotheses on Collective Memories of the Cultural Revolution,” The China Review 5.2 (Fall 2005): 13-41 # Peter Zarrow, “Meanings of China’s Cultural Revolution: Memoirs of Exile,” Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 7.1 (1999): 166-191. # Shuyu Kong, “Swan and Spider Eater in Problematic Memoirs of Cultural Revolution,” Positions, 7.1 (1999): 239-252. First Review is due by 4:30 PM on Sep. 29 (M) both on Caucus and at History mailbox. Oct. 1 (W) Historicizing memories How is Ye Weili and Ma Xiaodong’s accounts differ from Jung Chang’s “victim literature”? How do Ye’s seeming apathy to and Ma’s enthusiasm in joining the revolution go together? Weili Ye, “Even if you cut it…,” “Flowers of the Nation,” “From paper crown to leather belt.” Oct. 3 (F) Continuities & Discontinuities What are some enduring themes that cut across different phases of the Cultural Revolution (and beyond)? What might be limits of memory-based history? Weili Ye, “Up to the Mountains and down to the Countryside,” “Worker-Peasant-Soldier Students,” “The Reform Era.” Week 5: Oral History Oct. 6 (M) Private and Collective Memories In what ways, does an oral history-based narrative contribute to (or hinder) our understanding of the Chinese Revolution? What common agendas do the oral testimonies on the Cultural Revolution share? What are proper ways to read an oral history-based narrative? * “The Story of a Smile,” in Feng Jicai, ed., Ten Years of Madness: Oral Histories of China’s Cultural Revolution (San Francisco: China Books and Periodicals, Inc., 1996), 127-142. * “Avenger,” in Feng Jicai, ed., Voices from the Whirlwind: An Oral History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution (New York: Pantheon Books, 1991), 28-37. Oct. 8 (W) Going beyond oral testimonies What alternative ways do we have to read the Chinese Cultural Revolution? # Vera Schwarcz, “A Brimming Darkness: The Voice of Memory/ The Silence of Pain in China after the Cultural Revolution,” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 30.1 (1998): 46-54. # Sheng-Mei Ma, “Contrasting Two Survival Literatures on the Jewish Holocaust and the Chinese Cultural Revolution,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies 2.1 (1987): 81-93. 4 Oct. 10 (F) In-class screening: Carma Hinton, Morning Sun (clips) Second Review due by 4:30 PM on Oct. 10 (F) both on Caucus and at History mailbox. Week 6: Representing the Cultural Revolution I – Political History Oct. 13 (M) The First Salvos Suppose you were a censor of the CCP Propaganda Bureau and find out possible charges against the following drama. What do early moves of the Cultural Revolution tell us about the nature of the political use of a historical drama? (role playing & mock tribunal) Cheek, Doc. # 10, 169-179; Hinton, 173-212. Oct. 15 (W) Red Terror Who were the Red Guards? Why should there be an endless class struggle in a classless society like China? How would you account for the Red Guards’ participation in violence? Cheek, Doc. # 15, 210-5; Hinton, 215-239; 259-273. Oct. 17 (F) Doing a research – A Day at the Special Collection of the Gould Library What are Carleton’s connections to the Chinese Revolution? How would you use materials at the library relating to China for your own term paper? * Haldore Hanson, Fifty Years Around the Third World (Burlington: Fraser Publishing Co., 1986), 1-39. Oct. 20 (M) Midterm break – no class A Report (2-3 pages) based on your research of the China-related materials at the Special Collections and the Archives at the Gould Library is due by 4:30 pm on Oct. 21 (Tu). Week 7: Representing the Cultural Revolution II – Social History Oct. 22 (W) Historian’s Agenda What difference does it make to write a SOCIAL history of the Cultural Revolution? Esherick, 1-63 Oct. 24 (F) Interpreting Revolutionary Violence To what extent can we assess that revolutionary social violence was premeditated? Esherick, 64-152. Week 8: Representing the Cultural Revolution II – Social History (continued) Oct. 27 (M) Arts and Sciences in Making a Revolution What role did performing arts and popular sciences play in the making of the Cultural Revolution? Esherick, 153-239. Oct. 29 (W) Competing memories How would you account for the mood of nostalgia prevalent among sent-down youths in subsequent decades? Esherick, 240-265. 5 Thesis & Study Questions for your term paper are due by 4:30 P.M. on Oct. 30 (Th) at History mailbox and on Caucus. Oct. 31 (F) In-class film screening: Jiang Wen, In the Heat of the Sun (clips) A copy of a selection of one or two source materials is due on e-reserve by 4:30 pm on October 31 (F). Week 9: Nov. 3 (M) Building your arguments Discussion of your materials with your classmates II Nov. 5 (W) Discussion of your materials with your classmates II Nov. 7 (F) In-class screening: Carma Hinton, The Gate of Heavenly Peace (clips) Week 10: Giving your own verdicts Nov. 10 (M) Discussion of your materials with your classmates III Nov. 12 (W) Discussion of your materials with your classmates IV Nov. 14 (F) Individual Conferences An Outline and Annotated Bibliography are due by 4:30 P.M. on Nov. 14 (F) at History mailbox and on Caucus. Week 11: Oral Presentations: Nov. 17 (M) Presentations & Critiques Nov. 19 (W) Presentations & Critiques Your final research paper is due by 1:15 pm on November 24 (M). 6