Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial

advertisement

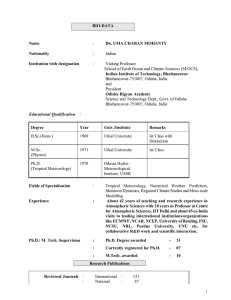

In Western feminist discourses, women from Africa and other parts of the socalled "third world" are often represented as objects against whom some writers affirm their own supposedly liberated status as Western feminists. Rather than interrogating the social, historical and economic conditions that oppress or disadvantage specific groups of women, many feminist writers have constructed a singular, ahistorical image of the oppressed, powerless 'Third World Woman'. In her article "Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses", Chandra Mohanty deconstructs this stereotype and asserts the need to historicize all analyses of women's oppression. In so doing, she hopes to identify alternative axes upon which international women's alliances and solidarity can be based. Her analysis thus provides a powerful critique of the pseudouniversalizing tendencies of hegemonic Western feminist discourse, and suggests new approaches for cross-border understanding of women's lives. However, her critique undermines the previously held notion of international feminist practice, and though she hints at new ways forward, Mohanty does not use this essay to interrogate the possibility for reconstructing a new universal womanhood. One of the key features of colonial discourse has been its misrepresentation or denial of the diversity of non-Western people. In order to survey and control their subjects, colonial administrators developed elaborate classificatory schemes under which all peoples could be subsumed. Rather than viewing them as agents within a specific social and political environment, colonial theorists reduced Africans to objects of their own interpretative gaze. Thus, stereotypical ideas of African subjectivity came to dominate Western discourses on Africa in general. As Mohanty points out, feminist discourse picked up on this trend in its "production of the 'third world woman' as a 1 singular monolithic subject." (51) In such a representation, "third world women" are portrayed as "sexually constrained… ignorant, poor, uneducated, tradition-bound, domestic, family-oriented, victimized, etc." (56) Mohanty argues that the stereotypical image of non-Western women is a reflexive exercise intended to affirm the identity of supposedly more liberated Western feminists. She notes that the image of degraded third world women "is in contrast to the (implicit) self-representation of Western women as educated, as modern, as having control over their own bodies and sexualities, and the freedom to make their own decisions." (56) Thus, such representations of African women by Western feminists are less concerned with the reality of African women's lives than with validating the supremacy of Western feminist discourse. Mohanty argues that the resulting imagery is that of "'Woman' - a cultural and ideological composite Other" whose connection with the material reality of "women as historical subjects [… is] arbitrary" and often unconnected. (53) Western feminism's preoccupation with non-Western women's oppression and lack agency is premised on the idea that 'men' and 'women' are preconstituted social groups and the notion that non-Western women fall outside of history. As Mohanty notes, the first supposition is based on the rejection of class, ethnicity and other factors in the shaping of one's primary subjectivity. It assumes that "men" and "women" enter social relations as preconstituted powerful (male) or powerless (female) subjects. (58) This substitutes "the sociological […] for the biological […] in order to create […] a [false] unity of women." (59) By portraying African women as 'victims of culture' without agency, Western feminists argue that these women "exist, as it were, outside of history." (62) Thus deprived of their capacity for socio-cultural production and historical 2 agency, these subjects exist solely as oppressed women in the eyes of Western feminists. In turn, these feminists assert the incompatibility between African femininity (defined in terms of oppression) and women's liberation. Mohanty argues that the premises of universalistic Western feminism are ethnocentric and fundamentally flawed. Rather than reducing all women (and men) to a Western historicity, she contends that analysts should investigate women as social agents within their own social, historical, cultural and class backgrounds and contexts. No culture is static or unitary, and any culture is constantly open to contestation and renegotiation by all those who are engaged in it. Rather than objects that are acted upon, Mohanty argues that women are agents whose multi-faceted identities are too often obscured by some strands of feminist discourse. In addition to identifying the ethnocentric bias of Western feminism and its ideals of women's liberation, Mohanty attacks the notion that one's subjectivity is predetermined by one's gender or sex, a conflation of the sociological and biological. (59) Like men, women from all parts of the world are multi-faceted social actors who do not owe primarily allegiance or identity to an ill-defined international womanhood. By challenging the notion of an inherent universal womanhood that exists outside of social relations, Mohanty disrupts the premise on which international feminism is based. She asserts that there is no universal patriarchal structure that conspires against all women universally as a group. (54) Rather, economic, cultural, religious and political factors can intersect in various historically specific moments to create situations in which women are oppressed. Women do not enter into social relations as oppressed people; they may become oppressed due to a variety of factors, which in some instances may 3 include gender. She also stresses that seemingly identical practices may be either oppressive or liberating (or anything else in between) depending on their socio-historical and political contexts. (68) As a result, Western feminist critiques of other societies based on Eurocentric gender norms are rendered irrelevant. Mohanty's challenge to the international women's movement exposes its fundamental flaws and reorients feminist approaches to gender relations in general. While eliminating its problematic aspects, she does not attempt to rebuild a universal feminist theory. She asserts that contextualized local studies should form the basis for cross-border understanding of women's oppression. "Sisterhood cannot be assumed on the basis of gender; it must be forged in concrete historical and political practice and analysis." (58) Thus, she appears to have given up any prospect of an imagined international community of women responding to global male hegemony. While perhaps producing more effective understandings of women's oppression, Mohanty's approach emphasizes differences over commonalities, and as such, risks further marginalizing nonWestern women from Western feminist discourse. In addition to her assertion that seemingly similar practices may have different meanings depending on their respective contexts, one could add that seemingly different practices may in fact be quite similar and thus represent axes for cross-border solidarity. However, as a critique of pseudo- universalistic Western feminism, Mohanty's work is a powerful reorientation of feminist approaches to women's oppression. 4