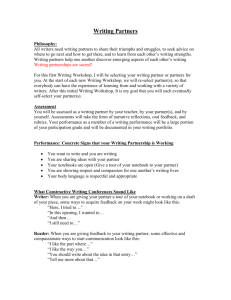

Writers in school [Word 190.5 KB]

advertisement

![Writers in school [Word 190.5 KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007769957_2-8ee292077aa675ba709264a186ee0960-768x994.png)