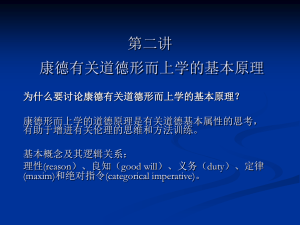

Kant`s Ethical Theory

advertisement

Kant’s Ethical Theory The Good Will Morality cannot be based on happiness or on any other type of consequences of our actions. Otherwise, morality would be based on circumstances that are, in part, beyond our control. Also, since we often cannot predict the consequences of our actions, we would often not know whether our actions are right or wrong. The only thing that is good “without qualification” is a good will. One has a good will if and only if he/she acts from the motive of respect for the moral law. Whether one’s act has moral worth depends on the motive from which he/she acts. The only motive that confers moral worth on one’s actions is respect for the moral law. A morally good action is not the same thing as a morally right action. Even if one does the morally right thing, he/she does not deserve moral credit unless he/she acts from a good will. Rationality and Morality Morality applies to human beings—not animals. Animals pursue pleasure. Therefore, the pursuit of pleasure cannot be the basis for morality. The reason that morality applies to human beings but not to animals is that human beings are rational beings (though imperfectly so). Human beings are rational because they are capable of following rules, reasoning to conclusions, generalizing, and making free choices. Rationality is not necessarily limited to human beings. God, angels, and extraterrestrial beings are other possible rational beings. Perfectly rational beings would naturally always act rationally. However, since human beings are imperfectly rational, they are often inclined to act irrationally. Morality requires of human beings that they act as perfectly rational beings would act. Since human beings are often inclined to act irrationally, the moral requirement to act as a perfectly rational being would act is in the form of an imperative (command) Imperatives—2 Classifications 1. Objective vs. Subjective A. Objective—expresses “how a fully rational being would act given certain aims or desires” (e.g., “A fully rational being who wants to be a great violinist will practice every day.”) B. Subjective (Maxim)—a rule of action that specifies the actions of imperfectly rational beings. (e.g., “If I want to be a great violinist, I shall practice every day.”) 2. Hypothetical vs. Categorical A. Hypothetical—prescription (“ought”) is conditional on the existence of certain desires (e.g., “If an individual wants to get rich, he/she will invest in the stock market.”) B. Categorical—prescription (“ought”) is not conditional on the existence of certain desires (e.g., “Always tell the truth”) Kant’s Theory of Right and Wrong Necessary Conditions for Right Action Morality applies to all imperfectly rational beings. Since morality would apply to non-human imperfectly rational beings, it does not depend on human nature or the particular circumstances of human life. Every voluntary human action commits the agent to a particular subjective rule of action (maxim). (e.g., If I go out to a restaurant for dinner, I am committing myself to some rule like “If I am hungry and don’t want to cook, I shall go out to eat.”) Morality must be unconditional. Therefore, all proper moral principles must be categorical imperatives. Moral rules must be universalizable—i.e., it must be conceivable for all rational beings to follow those rules, and the agents must be willing for that to happen. Kant’s Fundamental Principle of Moral Obligation—the Categorical Imperative First Formulation (CI1) Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law. Interpretation of “can at the same time will that it should become a universal law”— It must be possible for the maxim of one’s action to be a universal law—i.e., there must be no inconsistency in conceiving of everyone’s (all rational beings’) always following that maxim. (cf., deceitful promise example) It must be possible for the agent to will that his/her maxim to become a universal law—i.e., there must be no inconsistency between the agent’s aims and objectives in life and the prospect of everyone’s always following that maxim. (cf., wasting talents example) Second Formulation (CI2) Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in that of another, always as an end and never as a means only. Interpretation of “always as an end and never as a means only”— To treat someone as an end is to recognize him/her as a rational being deserving of the same respect as yourself and to treat him/her accordingly. Although we should not “use” others by deceiving or manipulating them, it is permissible to enter into social arrangements with them in which they knowingly and willingly perform services for us. (e.g., the waiter who brings us our food in a restaurant). This is the significance of the word “only” in the second formulation. Third Formulation (CI3) Act only so that the will through its maxims could regard itself at the same time as universally lawgiving. Interpretation of “universally lawgiving”— Since we are choosing the maxims for our actions, we are giving ourselves the moral rules rather than following the dictates of some authority or other—e.g., government, society, or even God. Since our maxims must be universalizable, in giving ourselves those moral rules, we are, in effect, legislating for everyone else as well. Objections to Kant’s Ethical Theory 1. It is doubtful that there is a single maxim associated with each action. For many actions, there appear to be multiple maxims on which the action could be based. 2. Kant’s assumption that we have a moral obligation to act as perfectly rational beings would act is not supported. 3. The claim that the consequences of actions have no effect on whether they are morally right or wrong is implausible. (e.g., lying to save the life of an innocent person)