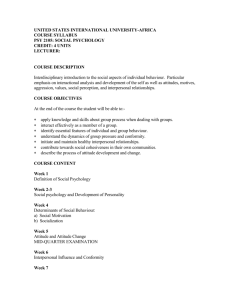

Figure 1. A Conceptual Framework of Identity vs. Bond in Online

advertisement