THE OFFICE OF ACADEMIC SUCCESS PROGRAMS

advertisement

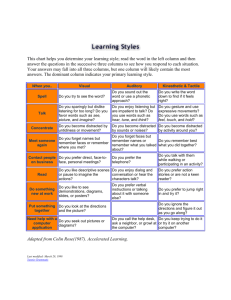

THE OFFICE OF ACADEMIC SUCCESS PROGRAMS WEEKLY STUDY TIPS FOR THE WEEK OF OCTOBER 16TH Dr. Amy L. Jarmon, Assistant Dean of Academic Success Programs Last week’s study tips looked at the absorption styles of learning styles which suggested ways in which you could study to “pull in” information to begin to learn it. This week, we are looking at the processing styles which indicate how you organize material. The processing styles often give clues to strengths and weaknesses on exams. Processing styles that give you clues to your learning are: global; sequential; intuitive; sensing; active thinker; reflective thinker. Learners will prefer global or sequential processing and intuitive or sensing processing. They will also prefer either active or reflective thinking. Here are thumbnail sketches of what these styles mean: Global: You prefer to know the “big picture” of a topic or course. Do not skimp on deep understanding, analysis and organization. Sequential: You prefer to learn unit by unit (case by case; sub-topic by sub-topic) and in systematic steps. Do not skimp on seeing the “big picture” and inter-relationships. Intuitive: You are very comfortable with ideas, abstractions, theories, and policies. Do not skimp on facts, details and practical application. Sensing: You are very comfortable with details, facts, and practicalities. Do not skimp on understanding the concepts, theories and interrelationships behind the law. Active thinker: You prefer to think about a topic while you do something with the information. Do not talk before you think or rush your thinking. Reflective thinker: You prefer to think about a topic before you have to do something with the information. Do not forget to explain to others how you got to a conclusion. A few ideas for those who prefer global learning: Use your professor’s syllabus or the table of contents of your casebook to provide you with a roadmap of a topic. Preview material that you will be studying so that you will know the overview of the material. o Listen carefully when the professor previews material you will cover in class. o Read carefully the introductory material provided in your casebook. o Scan a commercial outline, Nutshell, Examples and Explanations, or other study aid before reading cases on a new topic. Use graphic organizers to reflect the “big picture” in a course: tables; flowcharts; legal diagrams; mind maps; and other versions. Use methodologies to force yourself to memorize the organizational steps for analysis. Make sure that your outline is not too short – add enough detail to completely analyze the topics and sub-topics. Make sure that you learn rules and definitions of elements precisely so you can state them accurately. Use rule, definition and methodology flashcards to drill yourself on mundane memorization. Practice explaining concepts and hypothetical answers to others so that you are more organized, methodical and detailed in your discussion. Memorize a checklist of topics and sub-topics for a course so that you emphasize the steps of analysis needed. Beware of being conclusory on exams where you do not put down your analysis and instead focus on a right answer. Ask yourself “because” at the end of each statement on your exam and explain “why” if you did not do so in the statement. Write exam answers to your mother, little brother, or grandfather if it means you will be more detailed in analysis than when you write to the professor. A few ideas for those who prefer sequential learning: Summarize material after you have studied a topic or sub-topic so that you see the overview of the material. o Listen carefully when the professor reviews material that you have covered in class. o Re-read introductory material in your casebook after you have studied a topic. o Read a commercial outline, Nutshell, Examples and Explanations or other study aid after studying a topic in class. Use methodologies to reflect the organizational steps of analysis to particular topics and sub-topics. Use graphic organizers to force yourself to see the “big picture” in a course: tables; flowcharts; legal diagrams; mind maps; and other versions. Make sure that your outline is not focused merely on cases as separate units – organize it by topics and sub-topics so that you see the interrelationships. Use cases as illustrations of topics and sub-topics rather than as organizers in your outline. Practice explaining concepts and inter-relationships among concepts when you do hypothetical answers. Use rule/code section tables to assist in your organization of these rules and codes -- have one by topics/sub-topics and one by rule/code number. Use policy, theory and inter-relationship flashcards to drill yourself on the “big picture” for the course. Memorize a checklist of topics and sub-topics for a course so that you emphasize the inter-relationships. Organize your exam answers before writing so that you use your strength of being sequential in your thinking. Use methodologies to help you organize your answers on exams so that you will include all steps of analysis. A few ideas for those who prefer intuitive learning: In addition to understanding the policies, theories, concepts and their inter-relationships, focus on how to apply them in practical ways. Practice explaining the policies, theories, and concepts with examples of when they do and do not “work” using hypotheticals. When doing practice questions, make sure that you use all facts that are given in the fact pattern. Make sure that your outline is not so short that it does not include precise definitions of the rules and elements. Make sure that your outline does not just gloss the topics and sub-topics instead of having depth to it. Force yourself to spend time on memorizing the rules, definitions of elements and methodologies so that you are able to have precise statements. Practice knowing the case facts (if not the names) that illustrate the concepts if your professor wants you to analogize and distinguish on the exam. Memorize a checklist of topics and sub-topics for a course so that you do not lose sight of the possible sub-issues. Organize your exam answers before writing so that you will not leave out steps of analysis. A few ideas for those who prefer sensing learning: Make sure your outline focuses on the “big picture” of the course and not minutia. Make sure your outline covers only the essentials of a case and is not a repetition of your entire brief for a case. Condense any outlines longer than 50 pages for a course repeatedly until you have learned the material and condensed it to 25 pages maximum. Do not become so immersed in the details of cases that you miss the subtopics and topics that are important to the course. Do not re-read cases as your method of studying for the exam because the “big picture” is the key to exam success. Although you may be able to teach the law to your classmates, you need to practice application of the law to questions with new fact situations. Learn how to spot issues and not just to regurgitate everything you know about the law. Memorize a checklist of topics and sub-topics for a course so that you do not become bogged down in minutia within the topics and sub-topics. When doing multiple-choice questions, be wary of second-guessing yourself and arguing yourself out of the right answer. When doing fact-pattern essay questions, be wary of “phantom issues” because you are going outside the four corners of the fact pattern. A few ideas for those who prefer active thinking: Join a study group or have a study buddy so that you can talk through the material and practice questions. Explain the concepts to a friend, empty chair, or family pet to check your understanding. Use many practice questions to help you think through the application of the concepts and rules. Do not avoid the mundane memorization because you would rather chat about the material. Be careful that you do not “throw out” ideas about material without organizing the material properly. Use a dry erase board if it helps you to think through practice questions. Beware hurrying through practice questions rather than methodically analyzing them. Do not wait until the end of the semester to learn your outline because you will not know it in depth. Volunteer in class so that you can discuss the material. Beware of rushing through multiple-choice exams and picking by gut instead of thinking through answers. Beware of rushing through fact-pattern essay exams because you did not organize your answers before writing. A few ideas for those who prefer reflective thinking: Participate in a study group or study buddy situation where an “agenda” of topics to be discussed is agreed ahead. Be careful that you do not state conclusions in a discussion without the analysis explaining the conclusion. Take time to think about a question before you answer it -- do not hurry yourself in your analysis. Write down questions that you have for the professor or tutor and take the materials with you to which the questions refer. Do not wait until the end of the semester to learn your outline because you will not have time to think about the topics. Answer questions in class silently in your head so that you can check your answers if you do not want to volunteer. Capture hypotheticals and questions that go by too fast in class in your notes so that you can think about them later. Beware of becoming “stuck” in multiple-choice exams and spending too long per question. Beware of second-guessing yourself on multiple-choice exams and changing right answers. Beware of taking too long on one or two essay questions so that you do not finish the entire exam. If you have never completed surveys to determine your learning styles, then spend an hour that will have learning pay-offs. You can go on-line to take the VARK survey and the ILS survey for free. The website for the VARK is http://www.vark-learn.com/english/index.asp. The website for the ILS is http://www.ncsu.edu/felder-public/ILSpage.html. If you want to take additional assessments, you can visit the website: http://www.brevard.edu/fyc/resources/Learningstyles.htm#Top. If you have completed the two surveys but need more assistance in interpreting them, make an appointment with Dr. Jarmon. A one-hour appointment will usually be enough for a discussion of the learning preferences as they apply to you. These sessions focus on explaining the preferences, but especially on how to use your learning preferences in practical ways to be a more effective learner.