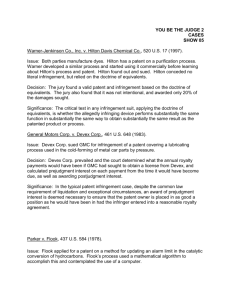

AIPLA`s Model Patent Jury Instructions

advertisement