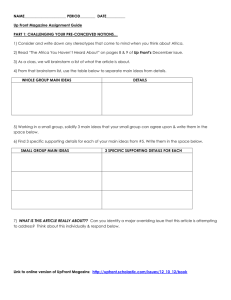

resubmission (11-Aug-09)

advertisement