Identifying a Student with Vision Impairment

advertisement

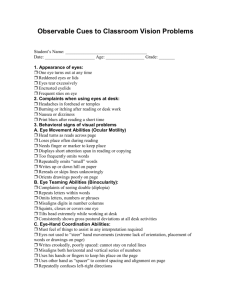

Teaching Students with Sensory Impairments Definitions, Identification, and Supportive Professionals II. Identifying a Student with Vision Impairment Dolly Bhargava Sometimes vision problems develop over time or they are so subtle that they have gone previously undiagnosed. Often a student can have vision impairment, but it may have gone unnoticed. The student is often the last one to recognize or report a loss in vision unless it has deteriorated. If the vision impairment remains undetected, it can result in the student facing a substantial educational disadvantage because of adverse effects on the student’s academic, communication, and social development. This can interfere with a student’s ability to reach full potential. On a medical note, if the vision problem is left undetected and untreated, it can cause permanent loss of vision and the long-term consequences can be serious in terms of quality of life. Consider the case of Koby, a 14-year-old boy who had undiagnosed type 2 diabetes. The undiagnosed diabetes led to many complications, including progressive cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, and vision impairment. Sadly, Koby’s teacher failed to recognize behaviors that were attributable to undiagnosed vision impairment. Some of them included his constant complaining that the lights in the classroom were too bright, difficulties with copying work correctly from the board and bumping into things in the room. The effects of the undiagnosed vision impairment were far-reaching and were responsible for reading and writing difficulties that he experienced throughout his schooling. A. Indicators of a Vision Impairment Source: Children with Low Vision: A Handbook for Schools Elmwood Visual Resource Centre, Christchurch, New Zealand Teachers need to be aware of the indicators that signal that a student has vision impairment. Table 1 is a guide that you can use to identify whether a child in your class has a vision impairment. Table 1 - A Guide for Detecting Vision Problems in the Classroom APPEARANCE OF EYES One eye turns in or out at any time Reddened eyes or lids Eyes tear excessively Encrusted eyelids Frequent styes on lids COMPLAINTS WHEN USING EYES AT DESK Headaches in forehead or temples Burning or itching after reading or desk work Nausea or dizziness Print blurs after reading a short time BEHAVIOURAL SIGNS OF VISUAL PROBLEMS Eye Movement Abilities (Ocular Motility) Head turns as reads across page Loses place often during reading Needs finger or marker to keep place Displays short attention span in reading or copying Too frequently omits words Repeatedly omits "small" words Writes up or down hill on paper Rereads or skips lines unknowingly Orients drawings poorly on page Eye Teaming Abilities (Binocularity) Complains of seeing double (diplopia) Repeats letters within words Omits letters, numbers or phrases Misaligns digits in number columns Squints, closes or covers one eye Tilts head extremely while working at desk Consistently shows gross postural deviations at all desk activities Must feel things to assist in any interpretation Eye-Hand Coordination Abilities required Eyes not used to "steer" hand movements (extreme lack of orientation, placement of words or drawings on page) Writes crookedly, poorly spaced: cannot stay on ruled lines Misaligns both horizontal and vertical series of numbers Uses hand or fingers to keep his place on the page Uses other hand as "spacer" to control spacing and alignment on page Repeatedly confuses left-right directions Visual Form Perception (Visual Comparison, Mistakes words with same or similar Visual Imagery, Visualization) beginnings Fails to recognize same word in next sentence Reverses letters and/or words in writing and copying Confuses likenesses and minor differences Confuses same word in same sentence Repeatedly confuses similar beginnings and endings of words Fails to visualize what is read either silently or orally Whispers to self for reinforcement while reading silently Returns to "drawing with fingers" to decide likes and differences Refractive Status (Nearsightness, Comprehension reduces as reading continued; Farsightedness, Focus Problems, etc.) loses interest too quickly Mispronounces similar words as continues reading Blinks excessively at desk tasks and/or reading; not elsewhere Holds book too closely; face too close to desk surface Avoids all possible near-centered tasks Complains of discomfort in tasks that demand visual interpretation Closes or covers one eye when reading or doing desk work Makes errors in copying from chalkboard to paper on desk Makes errors in copying from reference book to notebook Squints to see chalkboard, or requests to move nearer Rubs eyes during or after short periods of visual activity Fatigues easily; blinks to make chalkboard clear up after desk task Students with sensory disabilities have a wide variety of ways to learn and benefit from a curriculum that is shaped to meet their unique needs, skills, interests and abilities. They may need additional help in the form of special equipment and modifications in the typical curriculum to further develop listening skills, communication, orientation and mobility, vocational or career options, and daily living skills. But it’s exciting to realize that once we make these modifications, students can become full participants in their classes, establishing lasting friendships, and develop the skills to continue individual growth and pursue knowledge. B. Learning Characteristics Dolly Bhargava Vision is one of the most important senses. It plays a vital part in the learning process. It is held that more than 80% of education is presented through the visual senses (Pagliano, 1994). Lowenfield (1983), one of the early educational writers in the field, stated that, blindness imposes three basic limitations on an individual in terms of - Range and variety of experiences Ability to get about Control of the environment and the self in relation to it The extent to which a student is affected in these three areas will depend on the type and degree of vision impairment, resulting in the student having unique educational and learning needs. The student with vision impairment may lag behind in achievement in comparison to sighted peers due to the impact of visual impairment on learning. Therefore, the student will require skills to be specifically and explicitly taught, along with considerable additional time and opportunities to practice these skills. How do students who are blind or vision impaired develop an understanding of concepts, communication, social, orientation and mobility skills? How do they develop the ability to independently participate in everyday life activities? B - 1 Understanding Concepts Vision is the main sense that allows us organize, synthesize and integrate information received from the environment to help us develop concepts about the world and how it works. In the absence of vision or in the situation of limited vision the student often has to rely on the remaining senses of hearing, touch, smell, movement and taste to help assign meaning to the world. However, learning through the other senses is not always accurate and can sometimes result in a fragmented or partial understanding of the total concept. For example, feeling a raised outline of a tree is not the same in terms of the texture or size of a tree. This results in the student developing concepts based on limited and fragmented information as the student is unable to use his or her sense of sight to unify the different parts of the world and develop a complete picture of what is happening. Blindness and vision impairment result in a limited ability to explore the environment. In the absence of vision or in the situation of limited vision, the student cannot see classroom displays or range of activity options in the environment. The student will need systematic instruction on how to explore the environment, given the time to explore it in a way that is meaningful. The development of spatial concepts is also affected by vision impairment. This includes the ability to develop an understanding of where the body is positioned in relation to the classroom environment (Is the student in the front, back, or middle of the room? What is the distance from classroom objects such as a bookshelf or the teacher’s desk?) This further impacts understanding of directions such as up, down, right or left, in considering space and distance. Our sense of vision provides information on how we look and how others look and interact. This information is then incorporated into our own interactions. Students who are blind use other senses such as touch and sound to gain this information, limiting the extent of their knowledge. For example, knowing what one looks like by feeling one body part at a time may cause “difficulties understanding how all the different parts related to each other” (Lewis, 2002, pp. 63). And social appropriateness imposes restrictions on touching others. This inability to see others may provoke emotional responses and a sense of isolation. Time concepts such as morning, afternoon, and night are learned through observation and use. A child perceives differences between morning and night by seeing and making the connection between nighttime, associated with moon, stars, dark environment, whereas morning equates with sun and light. For a student who is blind, understanding such environmental concepts is difficult because of limitations with visually associating the concept with the discussion. We might consider the difficulty of explaining the concept of clouds or stars or the moon in the sky to someone who is blind. B - 2 Independent Living Skills These areas include personal hygiene, food preparation, money management, time management, and skills related to organizing personal space so it is easily accessible. For example, a child needing to prepare cereal for breakfast should first be familiar with the kitchen environment in order to locate the cereals, milk, and utensils. The child needs to know the process involved in preparing cereal, such as getting the bowl, spoon, cereal and milk. Next, it’s necessary to pour an adequate amount of cereal and milk into a bowl and take it to the dining table and afterwards wash and put things back in their original location. Students who do not have vision impairment learn this incidentally by observing others. However, students who are legally blind are unable to pick up these skills through observation and need direct teaching of these skills. B - 3 - Communication Skills These areas include receptive and expressive language. Communication is developed by having a variety of experiences where the involvement is as an active participant or learning by watching others. Due to visual limitations, the student may have had a limited variety of experiences and missed out on incidental learning. This effects the student’s understanding and expression. For example, a student without a vision impairment who has never given a speech before but has watched peers present would still have learned how to stand in the front of the room, face the audience, and speak in a loud voice. However, a student who is legally blind’s knowledge of giving a speech might be limited to someone talking about a particular topic, requiring direct teaching of such skills. Often, students with vision impairments are unable to associate words with discussion topics. For example, a student who is blind or has low vision may be hearing what the teacher is saying but cannot associate it with the drawing that the teacher has made on the blackboard or a demonstration of how to carry out an experiment. This may result in the student using or appearing to be comprehending words without fully understanding them In the absence of vision, the student may have difficulty identifying the similarities between objects via visual information (Dunlea, 1989) and difficulty with categorization Tobin (1997). For example, the student may know that an apple is a fruit. Yet, knowing that bananas, pears, peaches and oranges all belong to the same category although they don’t feel, taste or smell the same is something that would need to be taught explicitly. B - 4 Social Skill Development The term “social skills” is an all - encompassing one, which includes conversation skills, making friendships, dealing with feelings and classroom skills. We think of conversations as involving verbal and non-verbal communication. Non-verbal communication includes body language, facial expressions, gestures, mannerisms, tone of voice and appearance. A large part of messages is communicated non-verbally, such as through a nod, frown, smile, and shrug. A great deal of our interaction is based not only on our ability to understand verbal communication, but also the ability to read and understand non - verbal communication. We learn appropriate social behaviours by watching what other people do and copying them. Therefore a student may have good oral language but may lack the more subtle communication skills of gesture, posture, facial expression and general body language, which are so important. Students with legal blindness do not receive visual information from the environment to know where their friends are in the playground or how to read body language and facial expressions in order to judge how others are feeling or whether what they are saying is being understood or is of interest to others. B - 5 Orientation and Mobility Skills Many students who are blind or vision impaired experience difficulties with creating a mental map of their environment in order to figure out which direction to go or how to find their way round obstacles to reach their goal (Mason et al, 1997). It is extremely important that students receive orientation and mobility training to develop concepts, skills, and techniques needed to travel safely, efficiently, and independently in environments. Orientation skills refer to the thinking skills involved in knowing where we are in relation to the environment and the objects in it and how to find our way to the destination such as knowing that we are at the school bus stop and its location in relation to classroom or the assembly hall or the school office. Mobility skills involve the actual movement to our destination independently, safely, and with confidence. For example, if students want to get from their classroom to the school office, they need to be aware of the different clues or landmarks that they can use to independently get there. A crucial point to keep in mind all of these skills will need to be directly taught.