Microsoft Word

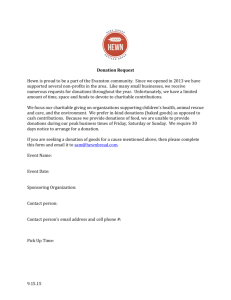

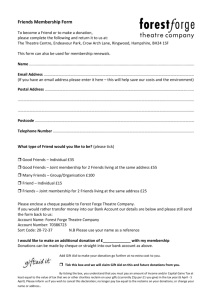

advertisement