Can one obtain an easement to protect an encroachment

advertisement

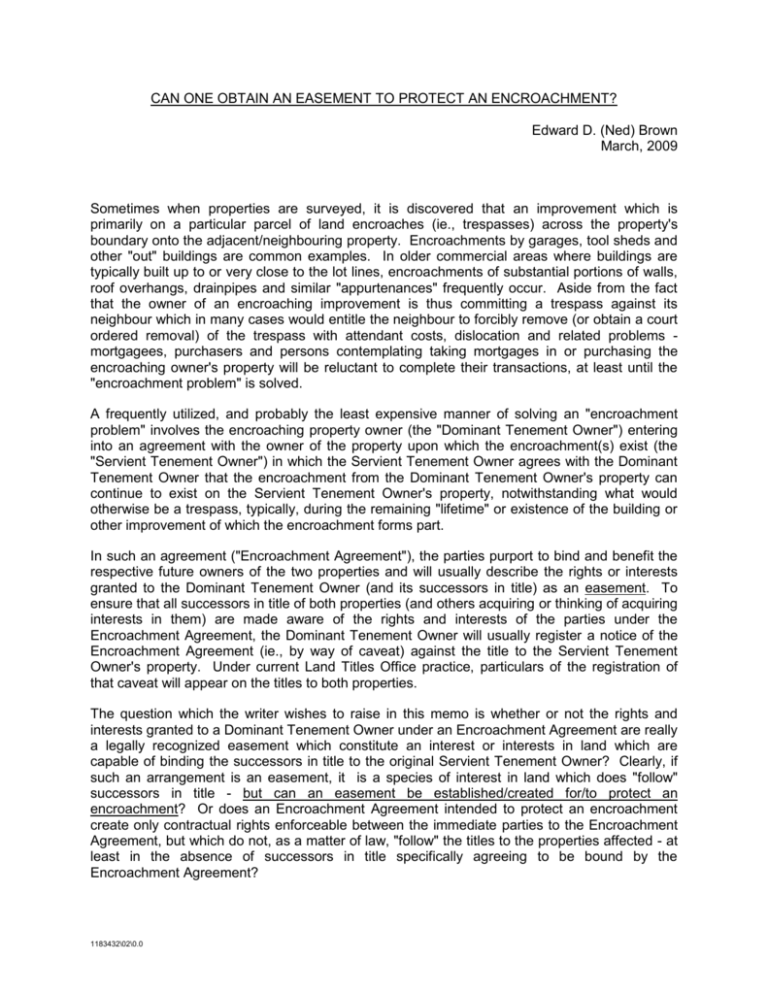

CAN ONE OBTAIN AN EASEMENT TO PROTECT AN ENCROACHMENT? Edward D. (Ned) Brown March, 2009 Sometimes when properties are surveyed, it is discovered that an improvement which is primarily on a particular parcel of land encroaches (ie., trespasses) across the property's boundary onto the adjacent/neighbouring property. Encroachments by garages, tool sheds and other "out" buildings are common examples. In older commercial areas where buildings are typically built up to or very close to the lot lines, encroachments of substantial portions of walls, roof overhangs, drainpipes and similar "appurtenances" frequently occur. Aside from the fact that the owner of an encroaching improvement is thus committing a trespass against its neighbour which in many cases would entitle the neighbour to forcibly remove (or obtain a court ordered removal) of the trespass with attendant costs, dislocation and related problems mortgagees, purchasers and persons contemplating taking mortgages in or purchasing the encroaching owner's property will be reluctant to complete their transactions, at least until the "encroachment problem" is solved. A frequently utilized, and probably the least expensive manner of solving an "encroachment problem" involves the encroaching property owner (the "Dominant Tenement Owner") entering into an agreement with the owner of the property upon which the encroachment(s) exist (the "Servient Tenement Owner") in which the Servient Tenement Owner agrees with the Dominant Tenement Owner that the encroachment from the Dominant Tenement Owner's property can continue to exist on the Servient Tenement Owner's property, notwithstanding what would otherwise be a trespass, typically, during the remaining "lifetime" or existence of the building or other improvement of which the encroachment forms part. In such an agreement ("Encroachment Agreement"), the parties purport to bind and benefit the respective future owners of the two properties and will usually describe the rights or interests granted to the Dominant Tenement Owner (and its successors in title) as an easement. To ensure that all successors in title of both properties (and others acquiring or thinking of acquiring interests in them) are made aware of the rights and interests of the parties under the Encroachment Agreement, the Dominant Tenement Owner will usually register a notice of the Encroachment Agreement (ie., by way of caveat) against the title to the Servient Tenement Owner's property. Under current Land Titles Office practice, particulars of the registration of that caveat will appear on the titles to both properties. The question which the writer wishes to raise in this memo is whether or not the rights and interests granted to a Dominant Tenement Owner under an Encroachment Agreement are really a legally recognized easement which constitute an interest or interests in land which are capable of binding the successors in title to the original Servient Tenement Owner? Clearly, if such an arrangement is an easement, it is a species of interest in land which does "follow" successors in title - but can an easement be established/created for/to protect an encroachment? Or does an Encroachment Agreement intended to protect an encroachment create only contractual rights enforceable between the immediate parties to the Encroachment Agreement, but which do not, as a matter of law, "follow" the titles to the properties affected - at least in the absence of successors in title specifically agreeing to be bound by the Encroachment Agreement? 1183432\02\0.0 The reason why the writer raises this question is because his recent review of the law pertaining to easements suggests that, while a right granted to a property owner to do something on its neighbour's land is generally recognized as an easement, the act, action, activity or usage made by the benefitted property owner must not amount to a right whose exercise completely excludes the neighbour's use of the affected property. For example, if the owner of Parcel "A" grants its neighbour the owner of Parcel "B", the right to use a pathway over "A"'s land, "A" still has the right to use its land, including the pathway. But where "A" grants it's neighbour "B", the right to maintain on "A"'s land, a part of a garage primarily situated on "B"'s land which encroaches over part of "A"'s land, then the encroaching portion of the garage, by the very nature of things, excludes "A" from in any way using the land underlying the encroachment. In other words, for the period of time during which the Encroachment Agreement is in effect, what "A" has granted to "B" is probably what amounts to a right of exclusive use/possession of the land underlying the encroachment. The writer submits that whatever such arrangement may be, it is strongly arguable that it is not an easement. But if an Encroachment Agreement does not create an easement, does it create any rights or interests in the affected lands over and above contractual rights and obligations between the original parties to the Encroachment Agreement? The writer submits that the answer to this question may, in many cases, be "yes", and that the rights or interests granted in the foregoing example are in the nature of a lease whereby "A" as lessor leases the land underlying the encroachment to "B" as lessee. As we all know, a lease is in fact an interest in land which is legally recognized as being capable of binding successors in title to the lessor. So if the parties to an Encroachment Agreement refer in it to the rights granted to the Dominant Tenement Owner as an "easement" (or "easements"), might a Court called upon to review the matter hold that the Encroachment Agreement is in substance a lease? Perhaps - or perhaps not - but even if an Encroachment Agreement is characterized as a lease, rather than as an easement, this raises another problem for the parties concerned (and their counsel). That problem is the existence of subdivision control rules (in The City of Winnipeg Charter Act and in The Manitoba Planning Act) which specifically exempt easements from the need to comply with subdivision control requirements, but which do not do so for a lease in excess (or capable of running in excess of) of 21 years. The writer believes that his above argument that one cannot obtain an easement to protect an encroachment is supported by the existence of Sections 27 and 28 of The Manitoba Law of Property Act. These Sections permit a (superior) Court to confirm or grant rights to an encroaching property owner in its neighbour's land to protect/with respect to encroachments made by the encroaching property owner on its neighbour's land. Why would the Legislature have enacted these Sections if it was not recognized that an easement either couldn’t be legally obtained, or was difficult to legally obtain, to protect an encroachment? In any event, these Sections make it clear that whether or not the Court provides relief to the encroaching property owner is in the discretion of the Court, so an encroaching property owner has no guarantee that it will achieve legal protection for its encroachment. If the writer is correct in the foregoing analysis, then it would appear appropriate for the Legislature to vary subdivision control rules to exempt leases which merely protect encroachments (regardless of their length or potential length) from subdivision control requirements. 1183432\02\0.0