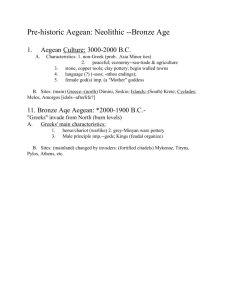

Excavations - Important - Bihar

advertisement