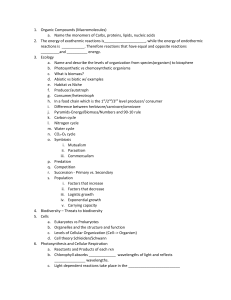

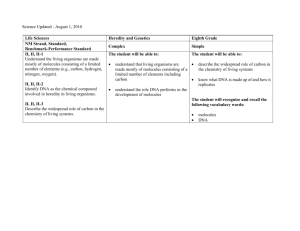

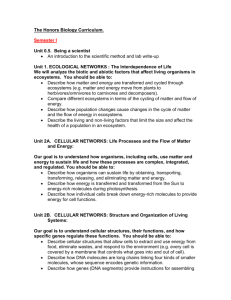

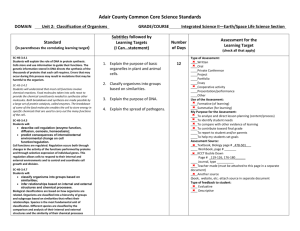

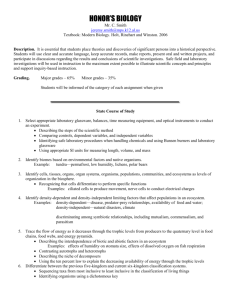

The Concept Outline

advertisement