Lecture : PHRASEOLOGY Phraseology and Phraseological Units

Lecture : PHRASEOLOGY

1.

Phraseology and Phraseological Units

2.

Vinogradov's Classification of Phraseological Units

3.

The origin of phraseological units

4.

Types of transference of phraseological units.

1. Phraseology and Phraseological Units

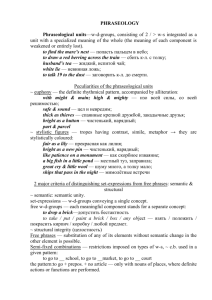

Phraseology is one of the sources of vocabulary enlargement and enrichment. It is the most colourful part of vocabulary system, and it describes the peculiar vision of the world by this speaking community. It reflects the history of the nation, the customs and traditions of the people speaking the language.

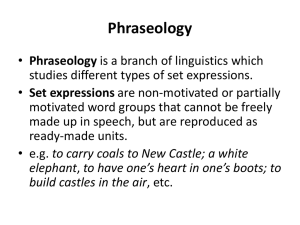

Phraseology forms a special subsystem in the vocabulary system. The units of the subsystem are called differently: phraseological units, phraseologisms, set expressions, idioms. The classification which will be distributed here is found on the fact that phraseology is regarded as a self-contained branch of linguistics and not as a part of lexicology.

Phraseological units are not modeled according to regular linguistic patterns, they are reproduced ready-made, e.g., to read between the lines, a hard nut to crack. Each phraseological unit represents a word group with a unique combination of components, which make up a single specific meaning. The integral meaning of the phraseological units is not just a combination of literal meanings of the components. The meaning is not distributed between the components and is not reduced to the mere sum of their meanings. Phraseological units are defined as stable word groups with a specialized meaning of the whole.

The meaning can be partially or completely transferred. Some features are usually stressed by this definition:

• Stability, the basic quality of all phraseological units. The usage of phraseological units is not subject to free variations, and grammatical structure of phraseological units is also stable to a certain extent, e.g., we say "red tape", but not “red tapes". Phraseological meaning may be motivated by the meaning of components, but not confined. Stability makes phraseological units more similar to words, rather than free word combinations. Correct understanding of the units depends on the background information.

• Idiomaticity, the quality of a phraseological unit, when the meaning of the whole is not deducible from the sum of the meanings of the parts.

• Reproducibility is a regular use of phraseological units in speech as single unchangeable collocations.

In lexicology opinions differ as to how phraseology should be defined, classified, described, and analysed. The word "phraseology" has very different meanings in this country and in Great Britain or the United States. In linguistic literature the term is used for the expressions where the meaning of one element is dependent on the other, irrespective of the structure and properties of the unit

(V.V. Vinogradov); with other authors it denotes only such set expressions which do not possess expressiveness or emotional colouring (A.I. Smirnitsky), and also

vice versa: only those that are imaginative, expressive and emotional (I.V. Arnold).

N.N. Amosova calls such expressions fixed context units, i.e., units in which it is impossible to substitute any of the components without changing the meaning not only of the whole unit, but also of the elements that remain intact. O.S. Ahmanova insists on the semantic integrity of such phrases prevailing over the structural separateness of their elements. A.V. Koonin lays stress on the structural separateness of the elements in a phraseological unit, on the change of meaning in the whole as compared with its elements taken separately and on a certain minimum stability. In English and American linguistics no special branch of study exists, and the term "phraseology" has a stylistic meaning, according to Webster's dictionary 'mode of expression, peculiarities of diction, i.e., choice and arrangement of words and phrases characteristic of some author or some literary work'.

As far as semantic motivation is concerned phraseological units are extremely varied from motivated, e.g., black dress, to partially motivated, e.g., to have broad shoulders or to demotivated like tit for tat, red tape. (Lexical and grammatical stability of phraseological units is displayed by the fact that no substitution of any elements is possible in the stereotyped set expressions, which differ in many other respects; all the world and his wife, red tape, calf love, heads or tails, first night, to gild the pill, to hope for the best, busy as a bee, fair and square, stuff and non sense, time and again, to and fro).

In a free phrase the semantic correlative ties are fundamentally different.

The information is additive and each element has a much greater semantic independence. Each component may be substituted without affecting the meaning of the other: cut bread, cut cheese, eat bread. Information is additive in the sense that the amount of information we had on receiving the first signal, i.e., having heard or read the word cut, is increased, the listener obtains further details and learns what is cut. The reference of cut is unchanged. Every notional word can form additional syntactic ties with other words outside the expression. In a set expression the information furnished by each element is not additive: actually it does not exist before we get the whole. No substitution for either cut or figure can be made without completely ruining the following: I had an uneasy fear that he might cut a poor figure beside all these clever Russian officers (Shaw). He was not managing to cut much of a figure (Murdoch).

2. Vinogradov's Classification of Phraseological Units

In his classification V.V. Vinogradov developed some points which were first advanced by the Swiss linguist Charles Bally. The classification is based upon the motivation of the unit, i.e., the relationship existing between the meaning of the whole and the meaning of its component parts. The degree of motivation is correlated with the rigidity, indivisibility, and semantic unity of the expression, i.e., with the possibility of changing the form or the order of components, and of substituting the whole by a single word. According to the type of motivation three types of phraseological units are suggested: phraseological combinations, phraseological unities, and phraseological fusions.

Phraseological combinations are partially motivated, they contain one component used in its direct meaning while the other is used figuratively: meet the demand, meet the necessity, meet the requirements.

In this group of phraseological units some substitutions are possible which do not destroy the meaning of metaphoric element. More examples: to attain success, to have success, to lose success . These substitutions are not synonymical and the meaning of the whole changes, while the meaning of the noun success and the verb meet are kept intact.

Phraseological unities are much more numerous. They are partially nonmotivated. Their meaning can usually be perceived through the metaphoric meaning of the whole phraseological unit, e.g., to stick (to stand) to one's guns – to refuse to change one's statements or opinions in the face of opposition, implying courage and integrity.

Phraseological fusions are completely non-motivated word-groups representing the highest degree of blending together, e.g., tit for tat. The meaning of components is completely absorbed by the meaning of the whole, by its expressiveness and emotional properties. Phraseological fusions are specific for every language and do not lend themselves to literal translation into other languages, e.g., white elephant – expensive but useless thing.

3. The origin of phraseological units.

The consideration of the origin of phraseological units contributes to a better understanding of phraseological meaning. According to the origin all phraseological units may be divided into two big groups: native and borrowed.

The main sources of native phraseological units are:

1.

terminological and professional lexics, e.g., navigation: to cut the painter

– to become independent, to lower one’s colours – to give in;

2.

British literature, e.g., the green-eyed monster – jealousy (W.

Shakespeare);

3.

British traditions and customs, e.g., baker’s dozen – a group of thirteen. In the past British merchants of bread received from bakers 13 loaves of bread instead of 12. The 13 th loaf was merchant’s profit.

4.

superstitions and legends, e.g., a black sheep – a less successful or more immoral person in a family or in a group. People believed that a black sheep was marked by the devil.

5.

historical facts and events, personalities, e.g., to do a Thatcher – to stay in power as prime minister for three consecutive terms.

6.

phenomena and facts of everyday life, e.g., to carry coals to Newcastle – to take smth to a place where there is plenty of it available. Newcastle is a city in Northern England where a lot of coal was produced.

The main sources of borrowed phraseological units are:

1.

the Holly Script, e.g., the kiss of Judas – any display of affection whose purpose is to conceal any act of treachery.

2.

ancient legends and myths belonging to different religious or cultural traditions, e.g., to cut the Gordian knot – to deal with a difficult problem in a

strong, simple and effective way.

3.

facts and events of the world history, e.g., to meet one’s Waterloo – to be faced with, esp. after previous success, a final defeat, a difficulty or an obstacle one cannot overcome (from the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815).

4.

variants of the English language, e.g., a hole card – a secret advantage that is ready to use when you need it (American).

5.

other languages (classical and modern), e.g., the fair sex – women, from

French: le beau sex; let the cat out of the bag – reveal a secret carelessly or by mistake, from German: die Katze ous dem Sack lassen.

4. Types of transference of phraseological units.

Phraseological transference is a complete or partial change of meaning of an initial (source) word-combination as a result of which the word-combination acquires a new meaning and turns into a phraseological unit. Phraseological transference may be based on simile, metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, etc.

1. Transference based on simile is the intensification of some feature of an object (phenomenon, thing) denoted by a phraseological unit by means of bringing it into contact with another object (phenomenon, thing) belonging to an entirely different class, e.g., as like as two peas, as old as the hills .

2. Transference based on metaphor is a likening of one object (phenomenon, action) of reality to another which is associated with it on the basis of real or imaginable resemblance, e.g., to bend smb to one’s bow – to submit smb; tongo to one’s long rest – to die.

3. Transference based on metonymy is a transfer of name from one object to another based on contiguity of their properties, relations, etc. the transfer of name is conditioned by close ties between two objects, the idea about one object is inseparably linked with the idea about the other object, e.g., a silk stocking – a rich, well-dressed man – is based on the replacement of the genuine object (a man) by the article of clothing which was very fashionable and popular among the men in the past.

4. Synecdoche is a variety of metonymy. Transference based on synecdoche is naming the whole by its part, the replacement of the common by the private, of the plural by the singular and vice versa, e.g., the components flesh and blood in the phraseological unit in the flesh and blood meaning – in a material form – as the integral parts of the real existence replace a person or any living being.