The story of the tutu: ballet`s signature costume has a fabled past

advertisement

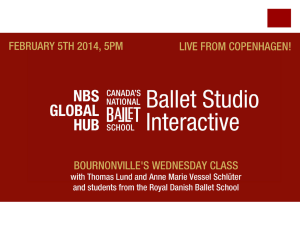

The story of the tutu: ballet's signature costume has a fabled past and a glamorous present Victoria Looseleaf Fashion may be fickle, but tutu chic is bigger than ever these days. While singing star Bjork caused a sensation draped in a white tulle dress with a swan's head wrapped around her neck at the Academy Awards in 2001, French designer Christian Lacroix continues to churn out haute couture balletic frocks of organza and tulle (matching ballet flats are also de rigueur). And some may recall the astonishing sum of $94,800 that a collector paid for the Leslie Hurry-designed tutu Margot Fonteyn wore in Swan Lake. Indeed, the tutu has a storied past. With a name probably derived from the French children's word "tu-tu"--meaning "bottom"--the costume is a product of evolution that made its debut in 1832, an instant classic, so to speak, that's been swathed in magic ever since. Marie Taglioni, performing on pointe (also a novel development then) and wearing a costume sometimes credited to Eugene Lami, danced the title role in the Paris Opera Ballet's production of her father Filippo's La Sylphide. Mesmerizing audiences in what was later dubbed a Romantic tutu, Taglioni's costume consisted of a tight-fitting bodice that left the neck and shoulders bare, and a diaphanous, bell-shaped skirt. Falling halfway between the knees and ankles, it was made of layers of stiffened tarlatan, or highly starched, sheer cotton muslin that gave the illusion of fullness without being weighty. Voila! A new tradition-and fashion statement--was born. While the dreamy appeal of a Romantic tutu is a joy to behold, romance can take a wrong turn. The first known tutu tragedy occurred in 1862, when 21-year-old Emma Livry, rehearsing for the Paris Opera Ballet, brushed her Romantic tutu skirt against an exposed gaslight, setting it on fire and causing her death eight months later from the burns she'd suffered. Undeterred, the evolution of the tutu marched on. By 1870 other Italian ballerinas, bent on perfecting pointe work, had begun wearing tutus cut above the knee, allowing them to showcase a bit more of their gams and increasingly complicated footwork, with ruffled underpants attached to the skirt. Known later as classical tutus and made famous by ballets like Swan Lake, these freer garments climbed farther north, becoming even shorter when ballet entered the 20th century, the added tarlatan layers creating a flared-from-the-body effect. Diaghilev's Ballets Russes experimented with different lines and looks. In 1927 the Russian constructivists Nauru Gabo and Antoine Pevsner designed an ultra-modern tutu for Balanchine's La Chatte, which had a transparent overskirt made of a plasticlike material. In the 1940s, wire hoops were inserted to enable the skirt to stand out from the hips. Tulle, a stiffened silk, nylon, or rayon fabric, soon replaced tarlatan, making the hoop an option, rather than a necessity. Still, there's a lot more to the tutu than, well, tulle. Its exterior splendor is made possible by an interior that supports the dancer (the bodice allows give, enabling the ballerina to move freely) and at the same time absorbs perspiration, while the voluptuousness of the skirt ingeniously conceals the trunks. With up to nine supportive layers, each cut progressively wider, and a 10th decorative top layer, the finished classical tutu is often ornamented with sequins, beads, or faux jewels. All done by hand, the costume can easily cost $5,000, with less fancy ones available from $1,500. A Romantic tutu, on the other hand, comprises five layers of tulle, each layer cut to about a 36-inch width. According to Jeanne Nolden, a tutu-maker who designs and builds costumes for Southern California's Inland Pacific Ballet studio, between 25 and 30 yards of fabric are required per garment. Nolden says that it takes about 60 hours to make a basic tutu. "It can be tedious, time-consuming, frustrating, and difficult. You vow, 'Never again!'--until the next time," says Nolden. "It is truly a labor of love, but if tutus are properly cared for, they can last up to 20 years." A tutu frames a dancer's movements, its construction supporting the physicality of ballet. Wearing a tutu generally marks a mature stage in a classical dancer's career, since nothing exposes the precision of classical technique as does the brief, jutting skirt with the snug-fitting bodice. Each tutu has its own history, with clues about its stage life and its relationship to the body buried deep within its seams. New York City Ballet's Maria Kowroski recently wore a tutu that had been worn by Suzanne Farrell. She never saw Farrell dance, but the sense of abandon that Farrell projected is the stuff of legend. "It's a weird feeling to think that she sweat in that costume," says Kowroski. "I thought maybe it would give me more freedom just to know that I'm wearing her costume." Then, only partly joking, she adds, "You never know what's gonna come out. You don't know if it has magic powers." American Ballet Theatre's Gillian Murphy, who performed the role of Aurora in the company's new Sleeping Beauty, says, "I love dancing in a tutu. It's light and beautiful and creates part of the magic." Murphy, whose mother began making tutus for her when she was 11, says that they are sometimes a problem for men. "A partner has to get used to the distance a stiff tutu creates between two people. He has to know where the ballerina needs to be by the feel of it, because the tutu limits his vision of her supporting leg." Occasionally the tutu does not fully cooperate. Vladimir Malakhov, ABT luminary and artistic director of the Staatsballett Berlin, describes an incident when he was partnering Amanda McKerrow in ABT's Coppelia. "At the end of the adagio, a hook from my sleeve stuck in her dress," recalls Malakhov. "I twisted my arm while lifting her behind my back, and when I put her down, I couldn't lift my arm because I was stuck to her costume. It didn't matter what position I took, we were stuck to each other. So I ripped open my sleeve and we did the variation." Ballerinas often have strong opinions about the style of tutu they prefer. When Baryshnikov was director of ABT, he created a Swan Lake that harked back to the 19th century when all the swans wore long tutus. However, Martine van Hamel wanted to wear short tutus as Odette and Odile for her 20th-anniversary performance. She preferred the way they "show the whole line" and she liked the more familiar tradition of short tutus for the Swan Queen. "I was going to hide them in my dressing room and wear them," she admits. Instead, she called up Baryshnikov, who by then was no longer artistic director, and asked his permission. "He said absolutely, that'll be fine." The gold standard of tutu design, Barbara Karinska, was a Russian-born emigre who built spectacular costumes for dance, film, theater, and opera. Although her Broadway and Hollywood career flourished, her heart belonged to dance, especially to the New York City Ballet and Balanchine. She dressed more than 75 Balanchine productions, and originated the "powder puff" tutu in 1950 for his Symphony in C. Its soft skirt distinguished it from the flat, horizontal "pancake" tutu (which is still favored by Russian dancers). Now housed in the basement of Lincoln Center in the wardrobe department of NYCB, Karinska's surviving handiwork totals about 9,000 costumes. "To help them stay stiff when they're not being worn," explains Holly Hynes, the designer who serves as consultant to NYCB's costume shop, "short tutus are hung upside down." Millinery spray starch can also help a tutu retain its shape, and layers of tulle are often replaced when a skirt loses stiffness. To keep the garments fresh, many are dry-cleaned after every three or four wearings (more ornate ones are dry-cleaned only before being returned to storage), while some are hand-washed after each performance. Willa Kim has designed costumes for opera, television, theater, and more than 125 ballets, including ABT's new production of Sleeping Beauty. Although Kim's dance costumes are not usually traditional tutu-wear, she appreciates the garment. "The tutu is an invention that belongs to ballet," says Kim, "and although it has been copied and has influenced designers and ready-to-wear, it is still an invention for the ballet and a remnant of the Romantic age. There are a lot of us who yearn for that kind of romanticism." Variations on a tutu theme have been rampant, with William Forsythe using a new design for his The Vertiginous Thrill of Exactitude, created in 1996 for Ballett Frankfurt. They are flat circles made of stretch material, not tulle, but still recognizable as a tutu. Oscar Wilde has said that fashion was "a form of ugliness so intolerable that we have to alter it every six months." But it seems unlikely that the tutu, with its fabled history and beautiful complexities, will go that route any time soon. "It has persisted as a beloved silhouette for more than a hundred years," Willa Kim says. "In the torso of the costume, you can include modern or stretch fabrics, but the silhouette has been set, is appreciated, and serves dance wonderfully." Victoria Looseleaf contributes to the Los Angeles Times and hosts a cable-access TV show on the arts. COPYRIGHT 2007 Dance Magazine, Inc. COPYRIGHT 2007 Gale Group