The Socratic Method: “The unexamined life is not worth living

advertisement

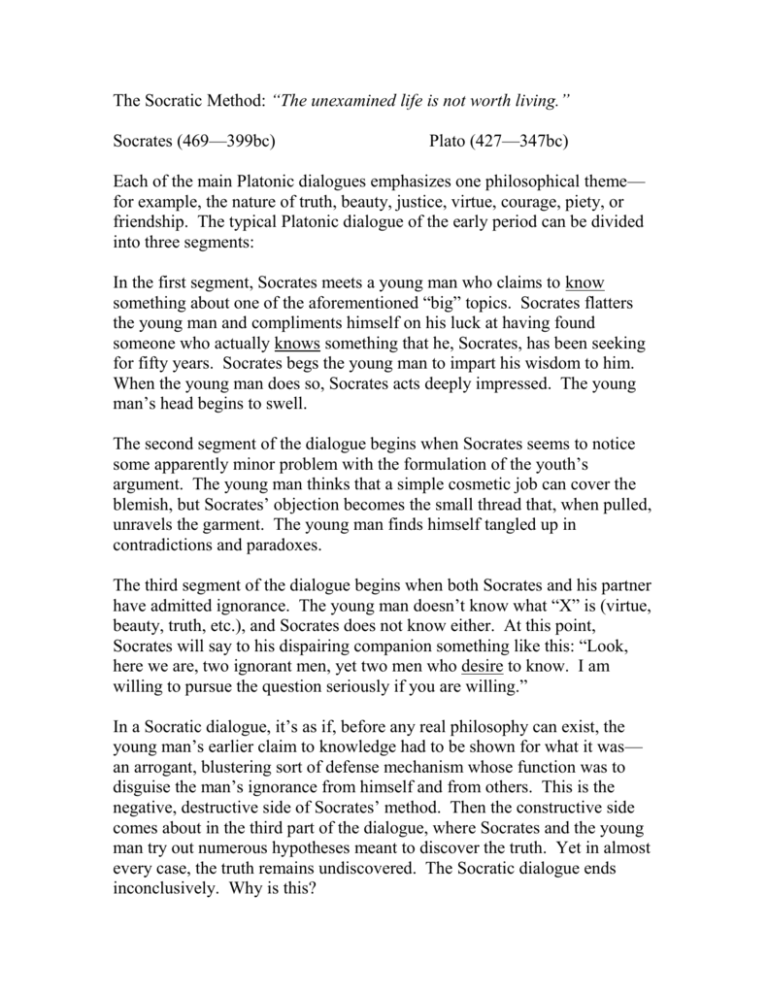

The Socratic Method: “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Socrates (469—399bc) Plato (427—347bc) Each of the main Platonic dialogues emphasizes one philosophical theme— for example, the nature of truth, beauty, justice, virtue, courage, piety, or friendship. The typical Platonic dialogue of the early period can be divided into three segments: In the first segment, Socrates meets a young man who claims to know something about one of the aforementioned “big” topics. Socrates flatters the young man and compliments himself on his luck at having found someone who actually knows something that he, Socrates, has been seeking for fifty years. Socrates begs the young man to impart his wisdom to him. When the young man does so, Socrates acts deeply impressed. The young man’s head begins to swell. The second segment of the dialogue begins when Socrates seems to notice some apparently minor problem with the formulation of the youth’s argument. The young man thinks that a simple cosmetic job can cover the blemish, but Socrates’ objection becomes the small thread that, when pulled, unravels the garment. The young man finds himself tangled up in contradictions and paradoxes. The third segment of the dialogue begins when both Socrates and his partner have admitted ignorance. The young man doesn’t know what “X” is (virtue, beauty, truth, etc.), and Socrates does not know either. At this point, Socrates will say to his dispairing companion something like this: “Look, here we are, two ignorant men, yet two men who desire to know. I am willing to pursue the question seriously if you are willing.” In a Socratic dialogue, it’s as if, before any real philosophy can exist, the young man’s earlier claim to knowledge had to be shown for what it was— an arrogant, blustering sort of defense mechanism whose function was to disguise the man’s ignorance from himself and from others. This is the negative, destructive side of Socrates’ method. Then the constructive side comes about in the third part of the dialogue, where Socrates and the young man try out numerous hypotheses meant to discover the truth. Yet in almost every case, the truth remains undiscovered. The Socratic dialogue ends inconclusively. Why is this? The Philosophical Attitude: a commitment to Reason Reasoning: an activity we sometimes engage in when we aim to answer a question, find a solution to a problem, resolve an uncertainty, or settle a controversy or dispute. When reasoning, we consider possible solutions to our problems, and then try to determine, using whatever evidence we can get our hands on, which is the best or “true” solution. When we want to make our reasoning explicit, we form arguments. Philosophical Virtues: critical reasoning 1. Critical Reflection—asking what the arguments (reasons) are for your beliefs and values, and whether those arguments are sound, clear, and relevant. To enhance critical reflection, we must be especially wary of the influence of self-interest, cultural-conditioning (closemindedness), and overconfidence (dogmatism). Before reasoning can begin, you’ve got to question. 2. Spirit of Inquiry—seeking out the best available evidence from the world around you to better answer your questions. Answers to our questions don’t come knocking, you’ve got to search for them. 3. Intellectual Honesty—wanting, above all, to know the truth about the questions your care about. We have to have the courage of our convictions, even if these truths are uncomfortable.