Possible elements to be included in the first speech to the HRC

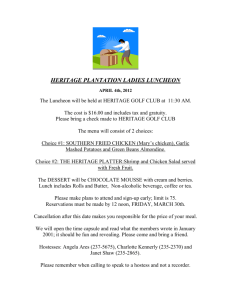

advertisement

Statement by Ms. Farida Shaheed, the Independent Expert in the field of cultural rights, to the Human Rights Council at its 17th session 31 May 2011 Mr. President, Excellencies, distinguished delegates, ladies and gentlemen; I am pleased to be here today to present the activities undertaken with respect to my mandate, including the reports submitted to this Council. In the past year, I continued to explore the meaning and scope of cultural rights. This year, I have focused on issues related to the right of access to and enjoyment of cultural heritage, which I believe is closely related to the right to take part in cultural life. To collect the views of all interested stakeholders, I disseminated a questionnaire on the subject and received many responses. In addition, I held an experts’ meeting on the right to access and enjoy cultural heritage on 8 and 9 February, and convened a public consultation in Geneva on 10 February. I am grateful for the insights provided by all those who participated, which were of great help in preparing the thematic report before you today. I am also pleased to report on my first country mission conducted in Brazil in October 2010. I conducted an official mission to Austria this year from 5 to 15 April and submitted a preliminary note. I will present a full mission report the next time I am before this Council. I wish to thank both Governments for their full cooperation and to express my appreciation of the fruitful dialogue which has been established with them. Addressing cultural heritage matters from a human rights perspective Excellencies, Allow me to elaborate on the research I have conducted on the need for a human rights-based approach to cultural heritage matters, and current developments in this regard. Cultural heritage is usually referred to as being tangible, intangible and natural. 1 The concept of heritage reflects the dynamic character of something that has been developed, built or created, interpreted and re-interpreted in history, and transmitted from generation to generation. From a human rights perspective, cultural heritage is also to be understood as resources that enable the cultural identification and development processes of individuals and communities. In the context of human rights, cultural heritage entails taking into consideration the multiple heritages through which individuals and communities express their humanity, give meaning to their existence, and build their worldviews. “...tangible heritage (e.g. sites, structures and remains of archaeological, historical, religious, cultural or aesthetic value), intangible heritage (e.g. traditions, customs and practices, aesthetic and spiritual beliefs; vernacular or other languages; artistic expressions, folklore) and natural heritage (e.g protected natural reserves; other protected biologically diverse areas; historic parks and gardens and cultural landscapes).” 1 1 My report refers to a number of fairly recent international instruments, including at UNESCO, which reflect this approach and stress the importance of the participation of individuals and communities, including indigenous peoples, in defining and stewarding cultural heritage. In these instruments, the definition of cultural heritage is not limited to what is considered to be of outstanding value to humanity as a whole. Rather, definitions encompass what is of significance for particular individuals and communities, thereby emphasizing the human dimension of cultural heritage. Human rights issues related to cultural heritage are numerous. They include questions regarding who defines what cultural heritage is and its significance; which cultural heritage deserves protection; the extent to which individuals and communities participate in the interpretation, preservation/safeguarding of cultural heritage, and have access to and enjoy it; how to resolve conflicts and competing interests over cultural heritage; and what the possible limitations to a right to cultural heritage are. It is especially important to bear in mind that cultural heritage encompasses things that are assigned significance. Therefore, its identification requires a selection process. Commonly, selection processes in which the State plays the main role, are reflective of power differentials; likewise, selection by communities may also indicate internal differences. The participation of individuals and communities in cultural heritage matters is thus crucial. One challenge is how to ensure that the people themselves, in particular source communities, are empowered, and that cultural heritage issues are not confined to preservation/safeguarding. Hence, cultural heritage programmes should not be implemented at the expense of individuals and communities who, sometimes, for the sake of preservation purposes, are displaced or given limited access to their own cultural heritage. The right of access to and enjoyment of cultural heritage Excellencies, In my report, I investigate the extent to which the right of access to and enjoyment of cultural heritage forms part of international human rights law. International and regional instruments concerning the preservation/safeguard of cultural heritage do not necessarily have a human rights approach. However, a striking shift has taken place in recent years from the preservation/safeguarding of cultural heritage as such, based on its outstanding value for humanity, to the protection of cultural heritage as being of crucial value for individuals and communities in relation to their own cultural identity. Generally speaking, the more recent the instrument, the stronger the link is with rights of individuals and communities. This is notable especially, but not only, in instruments relating to the safeguard of intangible heritage. I refer here to several UNESCO instruments and the interesting practices developed in implementing these, to the Convention on Biological Diversity, as well as regional instruments and initiatives in Africa, Asia, Europe and in the Pacific. It has been instructive to learn about efforts undertaken by a number of States 2 to ensure the involvement of individuals and communities in cultural heritage matters, and in ensuring their access to remedies in that respect. In international human rights treaties, I found that a number of provisions constitute a legal basis of a right of access to and enjoyment of cultural heritage. The right of access to and enjoyment of cultural heritage forms part of international human rights law, finding its legal basis, in particular, in the right to take part in cultural life, the right of members of minorities to enjoy their own culture, and the right of indigenous peoples to self-determination and to maintain, control, protect and develop cultural heritage. Other human rights must also be taken into consideration, especially the rights to freedom of expression, freedom of religion and belief, the right to information and the right to education. The right of access to and enjoyment of cultural heritage can be defined as including the right of individuals and communities to, inter alia, know, understand, enter, visit, make use of, maintain, exchange and develop cultural heritage, as well as to benefit from the cultural heritage and the creation of others. It includes the right to participate in the identification, interpretation and development of cultural heritage, as well as in the design and implementation of preservation/safeguard policies and programmes. I wish to stress that individuals and groups, the majority and minorities, citizens and migrants, all have the right to access and enjoy cultural heritage. However, varying degrees of access and enjoyment may be recognized, taking into consideration the diverse interests of individuals and groups according to their relationship with specific cultural heritages. I propose in this respect to particularly distinguish between: (a) originators or “source communities”, communities which consider themselves as the custodians/owners of a specific cultural heritage, people who are keeping cultural heritage alive and/or have taken responsibility for it; (b) individuals and communities, including local communities, who consider the cultural heritage in question an integral part of their community life, but may not be actively involved in its maintenance; (c) scientists,researchers and artists; and (d) the general public accessing the cultural heritage of others. This distinction has important implications for States, notably when establishing procedures for consultation and participation, which should ensure the active involvement of source and local communities, in particular. Taking into consideration the varied situations of individuals and groups is also of importance when States, or courts, are required to arbitrate conflicts of interests over cultural heritage. Indeed, the general public may not enjoy the same rights as local communities. Access to a monument or archives by tourists and researchers should not be to the detriment of either the object in question or its source community. Specific indigenous or religious sites may be fully accessible to the concerned peoples and communities, but not to the general public. 3 I conclude my report with some 14 recommendations addressed to States, to professionals working in the field of cultural heritage and cultural institutions, to researchers, as well as to the tourism and entertainment industries. These are difficult to summarize here. However, I wish to stress two key points. First, it is extremely important that States recognize and value the diversity of cultural heritages on their territories, and acknowledge, respect and protect the possible diverging interpretations that may arise over cultural heritage. Second, concerned communities and relevant individuals should always be consulted and invited to actively participate in the whole process of identification, selection, classification, interpretation, preservation/safeguard, stewardship and development of cultural heritage. In this, care must be taken to ensure the inclusion of the diverse views of individuals and sub-groups within concerned communities. Mission to Brazil Excellencies, From 8 to 19 November 2010, I undertook an official country mission to Brazil. I am please to report that culture, its governance, protection and promotion, occupies a central place in Brazil. A strong legislative and policy framework has enabled important efforts related to the protection and promotion of cultural rights. I wish to commend Brazil on its initiatives for retrieving, documenting, and revitalising cultural expressions and cultural diversity, encouraging mass participation in cultural activities and expressions, and facilitating access to libraries, theatres, cultural centres and museums. However, a number of measures require more effective implementation and many individuals and communities still do not feel fully appreciated as equal participants in national life. In particular initiatives should be strengthened that ensure communities are respected for their values and practices, build their self-esteem, and enable them to preserve the elements of their culture that they desire to keep, while participating in contemporary Brazilian society. Despite progress, a number of challenges remain and I recommend that Brazil continue to adopt all necessary steps to ensure the wider availability of cultural resources and assets, especially in smaller cities and regions, strengthen existing initiatives promoting the access and contribution of persons with disability, and bolster special provisions through subsidies and other forms of assistance for those lacking the means to participate in cultural activities of their choice. While in Brazil, I was informed of cases of religious intolerance, including acts of violence, against followers of Afro-descendant religions. Discrimination in the education system was also reported. It appears necessary for the Government to take a stronger stand and to redouble its measures to protect the believers, sites and expressions of Afro-descendant religions from imminent attacks, including by addressing the persistence of racism in Brazilian society and the negative image of African religions that is sometimes diffused by followers of other religions and/or the 4 media. I encourage Brazil to undertake participatory processes with communities and persons of African descent to address religious intolerance in the education system. Visiting the Guaraní indigenous peoples in Mato Grosso do Sul State, I observed two contrasting trends. On the one hand, Guaraní communities involved in ongoing land rights disputes reportedly suffer from a lack of self-esteem and the loss of cultural identity. On the other hand, some Guaraní communities, together with the academia and local government have undertaken activities enabling them to provide education in their own language, teach their belief systems, and promote their cultural manifestations. I encourage Brazil to address the concerns expressed by the Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, particularly regarding land demarcation and indigenous peoples' right to self-determination. I also encourage indigenous peoples to endeavour to strengthen their capacities to control and manage their own affairs, and to participate effectively in all decisions affecting them. Mr President and Excellencies, I wish to thank you for your attention. ----- 5