Gender in Fiscal Policies: The Case of West Bengal

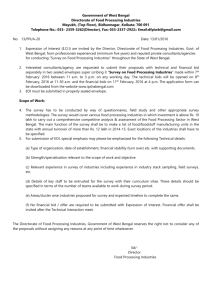

advertisement