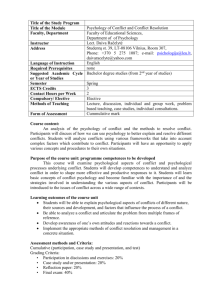

marketable_methods - University of Alberta

advertisement

1 Marketable methods Education as psychology’s primary market The fact is that from the beginning of the 20th c. psychology moved away from being a “pure science” to marketing its products. This meant that the market was able to influence the direction of the discipline’s investigatory practices. Practices that were useful in the construction of specific marketable products were more likely to receive a boost than those which did not produce such products. Of course, the fact is that the discipline also had the resources to produce marketable products. Most notably, (1) the Galtonian approach to individual differences and (2) the use of experimental treatment groups. Both methodologies made psychology into a socially relevant discipline. Of course, the availability of these two resources for socially relevant research also depended on the historical availability of institutions that would in fact avail themselves of these resources because they found them to be useful. One such institution was the field of education. It was the Herbartians of the 19th c. who laid the groundwork for this relationship between psychology and education (even though the Herbartians had little direct effect on the development of psychology). Charles Judd who was to have a prominent place in American educational psychology recalls, in1989 when he returned from Wundt’s lab and had been appointed professor at the School of Pedagogy at New York University, lecturing enthusiastically on Weber’s law to a class of teachers when he was interrupted by one gray-haired teacher auditor who asked “Professor, will you tell us how this law can in principle help us to improve my teaching of children”. Judd had no answer! What was it that educationists (and the institution of public education) required? Given the enormous differences in educational institutions and the social demands placed on schools in different countries, there was considerable national divergence in schooling. However, in the US the alliance between education and psychology was especially prominent even though what teachers required and what school administrators required was very different. Yet this link between psychology and education made psychology socially relevant. It should be noted of course that in the 1890s when psychologists like G. Stanley Hall became interested in child development, psychology’s contribution was fairly crude, restricted to a kind of psychological census taking, given the limited scientific background of teachers. Yet the important point was that there was established a conceptual link, even if very vaguely between psychology and education. After the turn of the century, psychologists’ relationship with teachers became increasingly overshadowed by a new generation of professional educational 2 administrators. This group took control of the educational systems adapting education to suit the changing order of corporate industrialism. The expansion of the American public educational system was nothing short of astonishing. Between 1890 and 1920 there was one public high school built each and every day and enrollment increases were of the order of 1000%. Between 1902 and 1913 public expenditure on education more than doubled and between 1913 and 1922 it tripled. In fact, professional educational administrators had little in common with classroom teachers. Indeed, this profession of educational administrators distanced itself from frontline classroom teachers (teaching was deemed to be a transient, unrewarding, unprofessional and female task) and established their own university curricula, journals, etc., and by 1914 became what we might call CEOs of educational systems. It was this profession rather than teachers which was psychology’s first market. Of course, professional educational administrators were not interested in psychology’s traditional experimental laboratory practices. Research for these professional administrators had to be relevant to their managerial concerns. This meant that research had to yield comparable quantitative data on the performance of large numbers of individuals (students) under restricted conditions (i.e., in schools). Occasionally, these professional administrators simply needed to justify the managerial decisions which they judged expedient for enhancing and maintaining the institution of public education. In fact, early educational administrators very frequently made use of an industrial metaphor: “education is a shaping process as much as the manufacture of steel rails”. Elaborate analogies were drawn between stockholders and parents, general managers of factories and superintendents of schools, foremen and principles, and industrial workers and teachers. Within that framework there was a natural carry-over from industry to education – both could be scientifically managed, which included: 1. measurement and comparison of comparable results, 2. analysis and comparison of the conditions under which the results were secured – especially the means and time it took to get the results, 3. the consistent adoption and use of those means to justify themselves most fully by their results, abandoning those that fail. Obviously, this scheme assigned a very important role to research, especially points 1 and 2, above, in order that appropriate action might be taken and justified in point 3 above. Today we call this “outcome-driven research”. Psychologists quickly responded to this scheme which required the kind of research that was very different from laboratory experimental studies or even the simply census-taking that characterized developmental psychology of child study by way of questionnaire. By 1910 a new Journal of Educational Psychology was established by Thorndike at Columbia Teachers College which saw a few traditional experimentalists like Carl Seashore and Edmund Sanford join the psychology devoted to “administration”. Sanford writes: “so long as the science must be financed by appropriations and endowments, the new psychology is called upon to furnish an effective defense against ignorant and hostile criticism and provide a tangible excuse for investment of institutional capital”. 3 What Sanford did not anticipate was that this alliance between psychology and educational administration would have consequences for psychology more profound than any contribution that psychology was likely to make to education. Thus 1. In the first place it broke with the kind of educational psychology that had been envisioned by the pioneering giants of American psychology such as William James, Baldwin, Hall and Dewey. These psychologists had envisioned a psychology of child study (of the child “mind”) but the new educational psychology demanded the management of (passive) children on the basis of performance measures so as to justify the allocation of financial resources. 2. But the new educational psychology proved popular because it could be extended to other domains as well, most notably the military administration during WWI. The methods of “mental” (test) measurement could be extended readily to the military. The entire field of applied psychology was now devoted to usefulness in administrative contexts. During the 1920 and 1930s large numbers of psychologist sought to produce psychological knowledge in service of practical contexts so much so that one prominent psychologist Woodworth spoke of psychology changing affiliation from philosophy to education. What this shift in allegiance came down to was that if knowledge is to be practically useful it was so in marketable administrative contexts. 3. The links between social (economic-political) administration and psychology affected both. Psychological practices had social repercussions but the demands of administration also affected psychological investigation. Thorndike for example held that the science of education (administration) will contribute abundantly to psychology! The demands of the market profoundly affected the research practices of psychology such that research could produce the kind of knowledge that was useful to the administration and education, military, business and industry. 4. This kind of knowledge was obviously statistical. Thus it was not the individual (mind) that was of interest but rather the individual’s performance relative to the performances of groups of individuals (i.e., “statistically constituted collective subjects”). Dealing with individual in terms of categories was the essence of administrative practices. 5. But the demand of administration was more specific than this. It also wanted methods for comparison of conditions and the measurement of results. E. C. Sanford, President of Clark University and a distinguished psychologist researcher, identified three methods that psychology could contribute to education and any rationalized social practice: (a) the standard laboratory study exemplified in German investigations of say memory by Ebbinghaus (a generation after Wundt), (b). the work on individual differences as exemplified by the method of mental testing (Galton), and 4 (c) the classroom experiment (pioneered by W. H. Winch in England, see below) in which school children matched in mental ability would be exposed to different method of instruction (conditions/interventions) and their performance would be assessed before and after the intervention (say, different instruction formats). So that children were assed prior to the introduction of the intervention and then a again after the introduction of the intervention – pre and post intervention design. The first (laboratory) and third methods (classroom experiment) compared the efficiency of different techniques of learning and instruction, the second method could be used to select individuals for certain programs (rather than the other way around). 6. If we examine these methods, we can begin with the second (individual differences – Galton) and third (classroom) methods: both individual differences and classroom experiments which depended heavily and directly on the educational market. I will examine the first experimental method later. Mental testing (individual differences) The too-ready marketability of mental tests profoundly affected the shape of psychological research (and the discipline of Psychology). After WWI there was an enormous expansion in the use of mental tests. This work had so little relation to the more traditional forms of psychological experimentation that eventually it seemed as if there were two distinct disciplines of psychology: one experimental and the other based on correlational statistics used in mental testing. (the “experimental” versus the “psychometric” or correlational traditions). Mental testing flourished because of interest in individual differences. However it should be obvious that the phrase “individual differences” is vague (it can refer to novelist’s work as readily as the psychologist’s) and indeed interest in individual differences preceded the work on mental testing (e.g., reaction time studies, somato-typing, physiognomy of the face, anthropomorphic measurements, and phrenology). What distinguished mental testing was not its interest in individual differences or its preference for quantitative methods, but rather the fact that the medium of mental tests severed the ancient link between psyche and soma and proposed to assess individual differences entire by measuring function. In practice this meant measuring performances in restricted situations. (Note no longer an interest in mind but in functional performances meaning performances in restricted situations to restricted response categories.) This amounted to a redefinition of the object of investigation; thus, psychological differences were now defined in terms of differences in measures of individual performance. It was performance at uniform set tasks that counted psychologically (and not for example facial expression or artistic style). On this somewhat restricted basis a broadly conceived study of individual differences was entirely possible. In fact, during the earlier periods prior to the quantitative study of individual differences (i.e., early in the 19th c.), most investigators were not interested in comparing individual 5 performances as such, but in characterizing psychological types and human individuality. Thus, before Alfred Binet developed IQ tests, Binet worked on “individual psychology” where psychological performance measures were used to assess an individual’s style of functioning. William Stern distinguished between the study of human variety and the study of individuality and accorded the latter a much higher status. James Mark Baldwin had criticized Wundt’s experimental psychology for ignoring individual style which Baldwin too conceived of in typological terms. What the development of mental testing did was to redefine the problem of individual differences (not in terms of typology or types but in terms of comparison of individual performances. Thus, the quality of a performance was no longer used to characterize the individual in terms of some universal type instead an individual’s performances measure was used to specify an individual’s position relative to an aggregate of individual performances. But in comparing an individual score to a group norm (mean) implies that characterizing an individual depends as much on the individual as it does on the group. The whole idea was that whatever individual characteristics were being measured these characteristics belonged to all individuals albeit in different quantities. Here is where we have the notion of a variable (as a universal characteristic that can be quantified in terms of different people’s values on the variable) and, ironically, rather than measuring the individual as different from other individuals, this method of mental testing actually eliminated individuals by reducing them to the abstraction of a collection of points in a set of aggregates. So that the statistical measurement of individual differences really constituted the very antithesis of psychological individuality, even as it also served to express directly a very different concern namely the problem of conformity. The practice of setting up norms in terms of which individuals could be assessed was however only “psychological” by inference since the norms were those of social performances and therefore carried powerful evaluative significance. Thus it was not an interest in the mental capacities that motivated the study of individual differences in performance but rather a way of assessing the individual who would most effectively conform to socially established criteria – ranging from “general intelligence” of the eugenicists to qualities needed to become a good salesman – all this was blatantly ideological and very practical. Throughout the 19th c. individual differences were of interest because (1) individuals in liberal democracies could advance themselves in competition with others, and (2) industrial and administrative institutions depended on categories of individuals to manage their businesses. With enormous rise of industrialization and bureaucratically managed/administered institutions in the19th c. there were two phenomena of particular interest to psychological practice: education and the management of social deviance. To way to deal with these there were two corresponding forms of “examination”: medical and academic. The latter was dealt with the selection of senior administrators, the former with dealt with psychiatric patients or criminals who were assessed for moral fitness (mental hygiene). Later in the 19th c. this distinction became blurred (the social category of “fitness” became a psychological category of “ability”), and given the Darwinian 6 influence the entire population was thought of as biologically fixed members of one class (everyone could be assessed/tested in terms of ability or some other psychological trait). Psychology exploited and was exploited to contribute the scientific classification of these “examinations” and did so through the expanded use of the “collective subject” involving large scale natural (e.g., “age” and “sex”) and psychometrically (e.g., “IQ” or “good learners”) defined groups. Individuals were of interest only as representatives of aggregates. In “psychological clinics” there still remained some interests in individuals (as in Binet’s original effort to determine individual children who needed special educational opportunities to succeed) but insofar as this practice was to have a scientific basis it required statistical norms (of the collective subject). The gap between understanding the individual mind and understanding the individual in terms of statistical norms seemed unbridgeable. Marketable mental testing ensured the dominant place in psychological research for a style of investigative practice that had been pioneered by Galton. This applied to the social construction of the investigative situation where some features of Galtonian anthropometry were exaggerated to the point of bizarre caricature in mass testing methods developed in the military and school systems (today this practice continues in university psychology departments). It also applied to the way in which statistical techniques were used to create the “objects” (collective subjects) that where in fact the real focus of the research (i.e., statistical distributions of scores contributed by a mass of individuals). The ready adoption of the Galtonian model by a significant section of American psychology is not surprising if one considers the parallels between the situation faced by Galton and by early 20th c. American psychologists. Galton wanted to establish a social science of human heredity (which one could never do so through controlled experiments and so used statistical comparison of group attributes). American psychologists were interested in promoting socially relevant science involving aspects of human conduct and performance that was also not accessible to precise experimental study under controlled laboratory conditions. The emerging psychometrics (biometrics) offered a statistical technique (initiated by Galton and Pearson) which promised a way around the problem (of not being able to experiment). Something that looked like a science could apparently be created through statistical rather than experimental means. Obviously, there is a problem about trying to establish knowledge claims on the basis of the Galtonian model. In the classical experiment the aim was to establish functional relationships between a (stimulus) variable under the experimenter’s control and the observers report (or later, when introspection was abandoned, the animal or human “response”), and therefore there was a fundamental asymmetry in evaluating functional relations was essential for making causal attributions (whether to the subject, stimulus effect, or both). However, the situation is very different in the Galtonian model. Here the experimenter must make attributions in a situation over which he has no control. That is, the 7 experimenter does not attempt to influence (intervene in) the situation and hence whatever functional relations there are (between different tests and test scores) are symmetrical in the sense that no cause can be attributed to any of the variables that are being tested. All that can be managed is to get a “covariance” (concomitant) measure (two things go together –a co-relation). The descriptive statistics of the Galton-Pearson school provide such measures. Thus, the co-relation constituted the functional relationship between variables. In contrast, in the traditional experimental model, statistics were only used to ensure reliability of observations. Hence, American psychology became bifurcated in the kinds of knowledge claims it offered. At first this produced a great deal of confusion. Only gradually there emerged a kind of official doctrine: the ideal of research practice is one that combined the manipulative aspects of the experimental model with statistically constituted objects of investigation. What was not noticed until much later that this “mix” deprived the experimental manipulation of its original rationale which was the production of some causal process in the individual psychophysical system. Interest had shifted to the statistical outcome of experimental trials as manifested in differences between individuals. This was quite acceptable to many psychologists who saw their research as developing methods of social control of individuals (control enabled prediction and vice versa). Such a psychology had to use measurements in order to make predictions about future effects that could be taken into account by administrators, etc. In principle such predictions (reliably expected on the basis of previous measurements) could of course be made on a purely statistical basis. But that would require large-scale research consuming extended time. Psychology would have to be far better established as a discipline before it could muster the resources for such research. Even then the social organization of research especially individual professional academic career patterns favored small studies in brief time. It is therefore not surprising that the Galtonian method did not establish its claim to social relevance on the basis of sophisticated long-term statistical studies. Of course, there was a highly effective short-cut available – namely to hitch the wagon to the prevailing preconceptions regarding causation in human affairs. Those preconceptions prescribed that human interaction was to be interpreted as an effect of stable, inherently causal factors characterizing each and every separate individual. The most important of these were defined as psychological in nature, intelligence and temperament to begin with. Such factors were causal in the sense that they set rigid limits for individual action and were themselves unalterable. We see here the link between hereditarian dogma and the whole motivation for the eugenics program. We see this in the reliance on the normal distribution which was thought to be the distribution of biological traits - the same in everyone except that everyone has slightly different values of the biological variables. Even where the hereditarian preconception 8 was dropped in favor of the environment (e.g, with Watson’s behaviorist declaration), the distribution of psychological characteristics commitment remained in place. The transformation of the old psychology of group differences by Galton resulted in an important development in the nature of groups that were carriers of psychological attributes. Originally, psychology had simply adopted the social categories (age and sex), but Galtonian use of statistics greatly facilitated the artificial creation of new groups whose defining characteristic (usually IQ performance) was based on the performance on some psychological test. A score on a mental test (these tests could be based on any category whatever from IQ to self-esteem to extroversion etc. etc.)) conferred membership in an abstract collectivity created for the purposes of psychological research. This opened up untold vistas for such research because psychologists could create these kinds of collectivities ad infinitum and then explore the statistical relationships between them. Origins of the treatment group I noted in the first half of the 20th c. psychology came to rely increasingly on the construction of “collective subjects” for generating knowledge claims. Such constructed collectivities were not found outside psychological practice but depended on the intervention of the investigator. Three types of artificial collectivities were distinguished. 1. Those that were the result of averaging the performance of individuals subjected to similar experimental conditions. This first type represented an outgrowth of the traditional experiment procedures (Wundt etc.). 2. Those that were constituted from scores obtained by some use of psychometric testing. This type owes its existence to the demands placed on psychological practice by the market place education and industry). 3. Those that were produced by subjecting groups of individuals to different treatment conditions – and this type also appear to have been produced by the market. We have seen that for example educational administrators (efficiency experts) expected that (a) psychological research could provide methods of measurement that would permit the comparison of results (comparing the performance of the individual to that of the group). This was fulfilled in “mental tests”. But they also expected that (b) psychology could evaluate the effects of various kind so intervention (say different teaching strategies or programs). To evaluate the efficiency of these different interventions, what was needed was a way of comparing the individuals who were the recipients of these different interventions. Traditional experimental psychology was of little help here because it focused on the individual mind alone. Here the pioneering work of W. H. Winch in England was important. Winch was a school inspector and he was interested in assessing the effectiveness of various classroom conditions on such factors of mental fatigue and transfer of training in students. To do this, he subjected equivalent groups of children to different 9 conditions, and taking relevant measures before and after the intervention (pre-post test design or quasi-experimental designs). There was nothing surprising about this method. Schools were under great pressure and individual students were not important compared to the overall effective functioning of the classrooms. What is interesting about these early classroom studies is that they took place in an institutional environment that allowed for the easy manipulation of intervention conditions. Thus, studies of work efficiency (in industry) readily took on experimental form. This work assessing the effects of varying work conditions on outcome productivity provided strong incentive for combining the use of group data with the experimental method. Treatment group approaches to research (the group defined by the treatment or intervention it was given) quickly became popular in the research journals. But unlike the educational classroom studies (which were restricted to the classroom and work at school), the work efficiency studies were concerned not just fatigue in the particular situation of the classroom but with fatigue and learning in general or in the abstract (in any situation). The history of the treatment group methodology ran somewhat differently in applied psychology than it did laboratory research. By the 1920s the treatment group procedure was being sold in the US as the “control experiment” and as the best way to evaluate the effects of various conditions of work efficiency. It also became the textbook method of educational psychology: “experimentation pays in terms of cash”. Technically the treatment method of defining groups became quite sophisticated expounding on randomization and complex experimental designs some two years before R. A. Fisher (1925) published his well-known text on the topic. Yet in spite of these promising beginnings, the history of the treatment group methodology was not exactly a success (as judged by the number of studies reported in J of Educational Psychology or the J of Applied Psychology between 1915 and 1936). For one thing there was almost no demand for this kind of methodology outside the educational context, for another the research occurred in institutional setting that allowed for little variation conditions of intervention. There was also disappointment with the results, and the claims made for the quantitative and experimental method had been wildly optimistic. Moreover, the shape of this kind of research was always at the mercy of bureaucracies and institutional requirements, and once the “cult of efficiency” was over, the expansion of this kind of research declined. More generally there were always limits on the use of the experimental approach in institutions that were geared to practical goals and interests. Not only can measurement be a practical nuisance in these contexts but it also can be seen as a threat to vested interests and traditional practices of the established power groups. Although psychologists could help in selecting individuals for pre-established programs, and could also help in the selection of different programs, the former was clearly the safer bet (or else risk upsetting the power that be). 10 Obviously this situation is very different in the laboratory where experimentation could be safely used as the preferred method. Thus, in the safety of the university laboratory, the kind of experimentation that had emerged in the applied setting could evolve into a vehicle for the fantasy of an omnipotent science of human control (as some saw psychology). Moreover, in its eagerness to become an autonomous science, American psychology was not inclined to humbly serve the educational or industrial work settings as so serve as “psychological technicians”; rather, they saw what children or workers did in school or factory as merely an instance of the operation of “generalized laws of learning” etc. that manifested themselves in all of human behavior. Thus, the treatment group methodology became, in the hands of an ambitious science, a methodology for providing the basis for universal laws of human behavior. By 1936, 35% of the J of Experimental Psychology used this methodology. Thus, academic psychology was not interested in assessing the effect of specific interventions in specific institutional contexts (what we today might refer to as “quality control research”); rather, academic psychologists were interested in interventions or treatments that affected all human behavior in all conceivable contexts. Here we have the pretentious claim that practical efforts to enhance performance was like “engineering” whereas the science of psychology sought the universal effects of intervention/treatment on all behavior and as such was like “physics”. The abstract laws of learning (during the heyday of behaviorism in the1920-1950s) were deemed to be like the laws of physics. Of course physics had to solve the problem of the variability of observations and the uniformity of laws but this was done by showing that errors (individual differences) in observation obeyed statistical regularities (relegated to “error variance”). This assumption allowed psychologists to retain their faith in the existence of abstract universal laws even as they were daily confronted by human and animal variability. The faith in universal laws produced an interpretation of variability in observations in terms of an assumption that individual behavior varied continuously on a common set of dimensions (a common “human nature”). This gave rise to a distinction between genuine laws of behavior and mere generalizations based on statistical observations. If this distinction could be avoided – and it certainly was – then the variability in observations could be turned into an advantage. Groups could be assessed in terms of the mean and standard deviation which made it terribly easy to produce generalizations (every experiment finds some “effects”!) which could then be expressed as “laws” (provided one lived in an academic culture that did not distinguish between statistical and psychological laws, of course). This accounted for the popularity of group experiments in “pure” (versus applied) psychology…. This pure psychology was really an abstract form of the practice of controlling the performance of large numbers of individuals by way of environmental intervention. Thus, the fundamental laws were relationships between these environmental interventions and changes in response to such interventions. Obviously for a science that aspired to laws between environment and response, treatment group methodology 11 in practical contexts served very well indeed. In transferring this kind methodology to the laboratory one can construct a model of the kind of world that is presupposed by the laws of the new science (bells of scientific materialism!). It is a world wherein individuals are stripped of their identity (their historical existence as individuals) and then become vehicles of the operation of totally abstract laws of behavior/environment defined over abstract collective subjects. Thus, the treatment group method was ideally suited for establishing knowledge claims about the relationship between abstract external influences and equally abstract organisms. Taking the same group of subjects through the same set of environmental variations could be used for this purpose (and was) but this approach provided subjects with a bit of history (even though it was only specially constructed experimental history) and this meant that the results could not be unambiguous interpreted. Only the treatment group could provide a practical construction that the so-called pure science of behavior required. As the use of treatment groups increased, the empirical basis for questioning the prevailing shape of psychological theory became narrower. That is, treatment group gave the kind of results that the theory of universal laws presupposed, namely that there are lawful relations between treatment intervention (environment) and behavior/response.