Conservation measures and actions required

advertisement

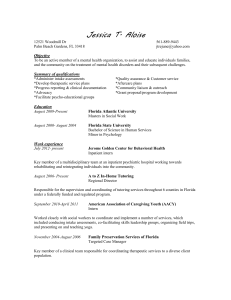

Conservation Action Plan Jacquemontia reclinata Species Name: Jacquemontia reclinata House ex Small (1905) Common Name(s): Beach jacquemontia, beach clustervine, fairy morning-glory Synonym(s): J. havanensis (Roberty 1952) Family: Convolvulaceae Species/taxon description: Root structure of perennial vine consists of fibrous root mass (10 x 15 cm) and numerous lateral roots, which can extend up to 2m (Wright 2003). Numerous lateral stems radiate from stout rootstock. Slender stems, woody at base, with many lateral branches, spreading along the ground and reaching lengths of up to 2.5 m long. Stems may twine or climb over other low vegetation, but generally do not ascend. Younger leaves and stems may have enough soft down to appear whitish; older leaves and stems may appear smooth. Leaves are entire, alternate, spirally arranged, and almost always have petioles. Leaf blades are 2 – 4.5 cm long and 0.5 – 2.5 cm wide, and may be fleshy, elliptic to eggshaped, with the apex rounded or slightly notched. Light levels may significantly affect the leaf size. Inflorescences are axillary, cymose or solitary. Flowers are white to light pink with corollas shaped like broad funnels or nearly flat, 2.5 – 3 cm. in diameter, with five broad lobes. Fruits are capsules, 4 – 6 mm long, opening by 8 valves, and light brown when mature. Seeds are 2.5 – 3mm long and 0.1 – 0.2mm wide, and generally occur 4 per capsule (Robertson 1971). Jacquemontia reclinata is closely related to J. havanensis, J. curtissii and J. cayensis. The species only occurs on the coastal dune community and can be distinguished from J. havanensis, J. curtissii and J. cayensis by the presence of tiny hairs along the margins of the outer sepals, and broad, succulent leaves (Austin 1979). Legal Status: Florida endangered, federally endangered, critically imperiled (FNAI, IRC) Conservation Status: Native. Endemic. Prepared by: Elena Pinto-Torres, Hannah Thornton, Samuel J. Wright and Cynthia Lane, Conservation of South Florida Endangered and Threatened Flora (ETFLORA) Project, Research Dept., Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden Last Updated: April 2004 (Wright) H. Thornton 1 Fairchild Tropical Garden Background and Current Status Range-wide distribution – past and present Florida: (Confidential) Population and reproductive biology/life history Annual/Perennial: Perennial Habit: Vine Short/Long-lived: Suspected to be long-lived; lifespan unknown. Plant grown at FTG nursery in large container lived to be over 10 years old (Thornton pers. comm.). Original plants in the field tagged by Kernan are at least 7 years old. Original plants outplanted at Site 6 are over 7 years old. Pollinators: Believed to have a generalized pollination system. Twenty-two species of insect pollinators were observed visiting flowers, mostly small bees and bee flies, some flies, wasps, butterflies and ants (Pinto-Torres and Koptur 2003). Flowering period: Flowers November to May (Robertson 1971). Flowers observed all year (Austin 1991, Pinto-Torres and Koptur 2003), with increased flowering after rain (Pinto-Torres, Thornton, and Wright pers. observation). Fruiting: Fruits throughout flowering season, November to May (Robertson 1971). Fruits all year (Austin 1991). Annual variability in flowering: May flower more after fire or other disturbance. Fire has been shown to stimulate flowering in congeneric species Jacquemontia curtisii (Spier and Snyder 1998). Annual flowering variability may be affected by rainfall. Peak flowering occurred in April and May, with spikes in flowering following rainy periods (Pinto-Torres and Koptur 2003), Growth period: Year-round Dispersal: Seeds are released by capsular dehiscence. Lateral stems radiate 2-3m from rootstock aiding in short distance dispersal. Water and/or insects, birds, small mammals, crabs may carry seeds. Seed maturation period: unknown Seed production: 0 – 4 seeds per fruit, Pascarella (unpublished data) discovered that fruits produce an average 3.47 seeds per fruit (n=30). Seed viability: Greater than 70% germination of seeds in the greenhouse (USFWS 1995); preliminary studies have shown that seeds will not persist more than a few months buried in the soil and long-term seed banks may not be a significant part of its life history strategy (Pascarella 2003). Percent germination of fresh seed is variable at 20-82% (Carrara 2001), but germination of >50% is common (Carrara and Garvue 2003). Seeds stored for five years under ambient conditions remained viable with 19-42% germination in four trials (Carrara and Garvue 2003). Germination requirements: Greenhouse experiments showed germination rates are higher in organic soils and shade (USFWS 1995), most likely due to higher degree of moisture. Soaking of seeds prior to sowing did not affect rate or percentage of germination, even though a yellow pigment was leached from the seeds (Fidelibus and 2 Fairchild Tropical Garden Fisher 2003). Seeds do not need light to germinate (Fisher 2003). Soaking in seawater does not affect germination (Griffin and Fisher 2003). J. reclinata requires arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi under natural soil conditions or where phosphorus is limiting (Fisher and Jayachandran 2002). Seed storage requirements: Preliminary results from a current experiment indicate that seeds are orthodox. Seeds in storage at -20°C for 3.5 years showed 10-50% germination, higher than seeds stored in 12°C or 23°C. Percent seed moisture content (SMC) did not seem to affect germination. Seeds dried to 5% SMC before storing germinated (Frances unpublished). Regularity of establishment: Transplants grow readily in the field (USFWS 1995, Wright 2003). Wild plants flower, set fruit and disperse prolifically, but few seedlings or young plants are found. J reclinata naturally colonize and stabilize disturbed areas on the lee side of dunes, but usually the aggressive invasives colonize first. Population size: Over 240 plants at largest population (Site 40), 177 plants at Site 39 and 144 plants at Site 23; other sites have less than 100 plants each (Kernan unpub. data). No current census of population numbers for these sites has been conducted since Thornton and LaPuma in 2000. During Fall 2003 site visits, Fairchild staff observed >50% reduction at Sites 14 and 53 (Maschinski et al. 2003b). Annual variation: unknown Number and distribution of populations: (Confidential) Habitat description and ecology Type: COASTAL STRAND, BEACH DUNE. Occurs on coastal barrier islands in disturbed or sunny, open areas within tropical maritime hammock or coastal strand (USFWS 1999); Coastal dunes (Avery and Loope 1980); Endemic to coastal sand dunes and hammocks along east shore of south Florida (Robertson 1971). Large plants are typically found spreading over exposed microsites on dune faces; rootstocks are sometimes found centered under a shading shrub. Plants also occur in mats or patches sometimes amidst tall grass or sea oats (Uniola paniculata) with stout rootstocks located throughout patch. In sunny sites, leaves may be fleshier and very pubescent; larger, thinner leaves have been observed in shady micro sites. Stems may twine around and over other vegetation, especially low shrubs. Woody rootstocks may persist under heavy mats of St. Augustine grass (Stenotaphrum secundatum), grass or other weedy species (Kernan 1995). Physical features Soil: Soil texture analysis from two naturally occurring sites showed that plots within J. reclinata habitat to contain 95% sand, 2 % silt, and 3% clay (Lane and Wright 2003) Elevation: From 1m to 9m above sea level (Lane and Wright 2003). Aspect: Mostly on crest and lee side of coastal dunes (Austin 1979), can also on the windward side of dunes. Slope: unknown Moisture: unknown 3 Fairchild Tropical Garden Light: Full sun; partial shade may be necessary for establishment (USFWS 1994), however a greenhouse study has demonstrated that plants grown in full sun were able to develop 40-70% higher root mass than those grown in the shade (Fidelibus and Wright 2003). This condition could favor survival in the wild. Biotic features Community: Disturbed, sunny areas in the coastal strand vegetation; typically alongside herbaceous species such as Helianthus debilis (beach sunflower), Cenchrus incertus (sand spur), Cnidoscolus stimulosus (stinging nettle), Cyperus pedunculatus (beach star), and some larger shrubs and dwarfed trees such as Coccoloba uvifera (sea grape), Metopium toxiferum (poisonwood), Trema micranthum (Florida trema). (Lane et al. 2001) Interactions: Competition: Plants respond to release from competition with vigorous growth (Kernan 1995, USFWS 1995) Mutualism: Generalized pollinator guild, possible ant mutualism Parasitism: n/a Host: n/a Other: Animal use: Ant nests, several species, often at rootstock or nearby, with ants traveling along stems. Natural disturbance Fire: May thrive after fire, e.g. Crandon population after 1996 wildfire (Kernan 1995; Lane et al. 2001). Hurricane: Historically thrives after disturbance, such as a hurricanes (USFWS 1994). Strong winds of hurricanes and tropical storms could aid in dispersal of seeds. Slope movement: Can survive burial; although not common, stems with adventitious roots may help stabilize dunes. Small scale (i.e. animal digging): Grows well in gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) habitat at Site 45. Small ghost crab (Ocypode quadrata) holes observed in sandy substrate next to plants at Site 6 (Wright pers. obs.) Temperature: Seedlings may be temperature sensitive (Carrara pers. comm.). Protection and management Summary: Jacquemontia reclinata is a federally endangered species and therefore has protection on all federal properties. All known wild populations are in conservation areas, however none are on federal property. One conservation area has cleared sea grape canopy for 15-years to maintain an opening for the population (Bass pers. comm.). Dune crossovers have been built at most conservation sites to limit damage to the coastal dune habitat. Additional management efforts have been directed toward removal of exotic species, trash and trails through dune habitat. Several outplantings have augmented or increased numbers of Jacquemontia reclinata. Techniques for greenhouse cultivation of seeds and cuttings from wild plants have been developed and provide material for outplanting efforts. Long-term seed storage techniques may supplement living ex-situ 4 Fairchild Tropical Garden collections in maintaining the genetic diversity of the species. Mycorrhizal inoculation and fertilization promotes establishment and persistence of outplanted individuals. Availability of source for outplanting: (Confidential) Availability of habitat for outplanting: (Confidential) Threats/limiting factors Natural Herbivory: The size of individual plants at the 2001 outplanting site of Site 6 has been significantly reduced by herbivory; marsh rabbits are suspected. We observed larvae of the bagworm moth foraging on the seedlings of a seed germination experiment at Site 102 (Wright per. obs.). Disease: unknown Predators: unknown Succession: Late-successional species may provide favorable conditions for germination, but may shade-out juveniles and adults Weed invasion: Exotic species: Casuarina equisetifolia (Australian pine), Schinus terebinthifolius (Brazilian pepper), Cupianiopsis anacardoides (carrotwood), Colubrina asiatica (latherleaf) (USFWS 1994), Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon)(USFWS 1999), Stenotaphrum secundatum (St. Augustine grass)(Kernan 1995) and Dactyloctenium aegyptium (Durban crowfoot grass); native species: Caesalpinia bonduc (knickerbean), Coccoloba uvifera (seagrape), Dalbergia ecastophyllum (coinvine) and Cassytha filiformis (lovevine) are invasive in coastal strand areas and can outcompete J. reclinata (Thornton and Wright 2003). Fire: May be killed by intense fire. Genetic: The species shows low levels of genetic variation relative to other rare endemic taxa; however, there is little evidence of differentiation between populations due to genetic drift. Inbreeding depression may be a threat, especially in the smaller populations. Given that most fragmentation of populations has occurred within the last 50 years, genetic drift is likely to be a threat in the future (Thornton 2003). Other: Encroachment of hardwood hammock follows long periods of fire suppression within the coastal strand (Austin and Coleman 1977, Richardson 1977, Wright 2003). Beach erosion can also seriously threaten this species (Johnson et al. 1990, Pilkey et al. 1994). Anthropogenic Coastal erosion and hammock encroachment may be directly related to human activities. On site: Coastal dune habitat is vulnerable to urbanization (Austin 1979), manicured landscaping, shade from exotic trees like Australian pine (USFWS 1994, 5 Fairchild Tropical Garden USFWS 1995), bulldozing and raking of natural beach sand dunes, use of herbicides and pesticides (may negatively affect natural pollinators), and trampling. Off site: Urbanization, pollution, encroachment and sea-level rise (USFWS 1994, Robertson 1971). Collaborators Greg Atkinson, Palm Beach County, Rob Barron, Coastal Growers Inc. Steve Bass, City of Boca Raton, Susan Carrara, FTBG Santiago Corrada, City of Miami, Paul Davis, Palm Beach County Janice Duquesnel, State of Florida Juan Fernandez, City of Miami Anne Frances, FTBG Dr. Jack Fisher, FTBG Dr. Javier Francisco-Ortega, FTBG, Florida International University (FIU) Raul Garcia, City of Miami Jim Gibson, State of Florida Liz Golden, State of Florida Frank Griffiths, Palm Beach County Jim Higgins, State of Florida Dr. K. Jayachandran, FIU Jim King, Miami-Dade County Dr. Suzanne Koptur, FIU Ernie Lynk, Miami-Dade County Linda MacDonald, Miami-Dade County Joe Maguire, Miami-Dade County Carol Morgenstern, Broward County Dr. John Pascarella, Valdosta State University Ginny Powell, Palm Beach County Renate Skinner, State of Florida Sonya Thompson, Miami-Dade County 6 Fairchild Tropical Garden Conservation measures and actions required Research history: Kenneth Robertson completed a morphological study of the genus Jacquemontia in which he treated Jacquemontia reclinata as a distinct species (Robertson 1971). Carol Lippincott completed surveys and some outplantings at Site 23 in 1990. She took notes and recorded the locations of naturally occurring individuals, and outplanted 17 individuals at three sites within the park. Naturally occurring individuals were relocated and mapped by Kernan and Garvue in 1995 using GPS. Kernan and Garvue were unable to relocate individuals at two of Lippincott’s reintroduction sites, but four plants were believed to have survived at the third site. (Kernan 1995) Dena Garvue worked to establish an ex situ collection of J. reclinata at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, and completed research on techniques for efficient horticultural propagation. The resulting collection of plants included individuals raised from cuttings and seeds from six naturally occurring J. reclinata populations. Garvue successfully propagated plants from cuttings 15 – 20 cm long. Cuttings were treated with rooting hormone and misted frequently on flats of beach sand for two weeks. Seedlings were then transferred to individual pots. She also showed increased rooting success after treating cuttings with concentrated hormone solution. Garvue also propagated plants from seed and her results suggest that seed germination success decreases with increased burial depth. (Kernan 1995) Christopher Kernan conducted experimental outplantings at Site 23 to determine expected survival rates of outplanted propagules derived from both seeds and cuttings in different microhabitat conditions. Survival of outplanted cuttings was greater in partial shade than in full sun, and Kernan’s results suggested that dune topography did not affect the survival rate of outplanted cuttings. Kernan found that outplanted seedlings did not survive as well as cuttings, but this may have been due to the small size of seedlings used in experiments. (Kernan 1995) Kernan also completed research to test the effects of two different outplanting site preparation techniques: treatment with herbicide and removal of competing vegetation. Application of herbicide without removal of the resulting mat of dead vegetation reduced the survival rate of outplanted J. reclinata cuttings. Kernan concluded that outplanted propagules would survive best in open sites hand-cleared of competing vegetation. (Kernan 1995) Kernan and Garvue surveyed and mapped J. reclinata populations at Sites 40, 39 and 23 using GPS with sub-meter accuracy. Kernan established and sampled vegetation plots at Site 23 to determine the preferred microhabitat of J. reclinata within the coastal plant community. Twenty-one plots, either 5 m x 5 m or 1 m x 1 m in size, were established along four transects running east to west from strand edge to coastal hammock. Kernan subjectively chose plot locations in order to represent changes in vegetation along the transect. Principal Component Analysis indicted that J. reclinata prefers partial shade. (Kernan 1995) Christopher Kernan conducted preliminary demographic studies on individual plants at Sites 40, 39, and 23 measuring both the diameter of the basal stem and length 7 Fairchild Tropical Garden and number of lateral stems. The study at Site 23 was interrupted by a wildfire (May 1996) that burned over the J. reclinata population for several days. Monitoring soon after the fire indicated over 70% of the plants was lost; however, in subsequent monitoring in 1999, Hannah Thornton and David La Puma were able to relocate many of these plants. Kernan also found that the fire drastically altered the habitat at Crandon Park, significantly decreasing the amount of St. Augustine grass, a major competitor before the fire. (Kernan 1995) Palm Beach nursery grower and landscaper Rob Barron outplanted J. reclinata in numerous Palm Beach privately owned properties. Seed from sites 125,133, and a nearby private site produced the majority of his original stock. Plants planted at Village of Key Biscayne are originated from Site 23 stock (Barron pers. comm.) In 1997, Janice Duquesnel and Liz Golden of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection outplanted J. reclinata was at Site 6. Fairchild donated the plants. Only seven of the original 93 plants have survived 6.5 years after planting. Reasons for low survival rate may be herbivory, storm surge, and/or poor initial health. At the time of planting the health of some of the plants appeared to be declining. It is assumed that most of the plants died due to poor initial health rather than as a result of the outplanting. In 2003, Hannah Thornton completed her study of the genetic structure of the remnant populations at the molecular and morphological levels. (Thornton 2003) In 2004, Elena Pinto-Torres completed her study of the breeding system and pollination biology. (Pinto-Torres 2004) Jack Fisher and K. Jayachandran studied the influence of mycorrhizal fungi on growth and survival, especially in outplanting. Found that under natural soil conditions J. reclinata requires Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), but is independent of AMF when Phosphorus is not limiting. (Fisher and Jayachandran 2002) John Pascarella is researching demography, including population growth rate, demographic performance, and temporal and spatial demographic variation. Cynthia Lane and Samuel J. Wright have completed studies describing associated vegetation, microhabitat, soil characteristics, sand accretion, and salt spray across the habitat gradient of J. reclinata. (Maschinski et al. 2003a) Wright identified a ranked list of potential restoration sites for J. reclinata and prepared restoration plans for the highest priority sites. (Maschinski et al. 2003a) Matthew Fidelibus and Wright studied the effect of shade treatment on shoot and root dry mass. Plants grown in full sun developed 40-70% higher root mass than those grown in the shade. (Wright and Fidelibus 2004). A paper was published in Native Plants Journal in Spring 2004 (Wright and Fidelibus 2004) Thornton compiled the history of J. reclinata conservation by searching written records, examining historical photographs and conducting interview with J. reclinata related land managers and naturalists. Thornton and Wright developed site-specific recommendations for management of population and distributed to land managers. (Maschinski et al. 2003a) Wright and Maschinski are currently conducting research of the seed germination rates and seedling survival of J. reclinata. Susan Carrara and Dena Garvue summarized optimal methods and conditions for J. reclinata propagation and seed storage, and evaluated the most effective protocols for 8 Fairchild Tropical Garden outplanting (Carrara 2001, Carrara and Garvue 2003). Frances is currently conducting seed germination trials to test the effects of different storage treatments (temperature, seed moisture content) on seed viability. Preliminary results indicate that J. reclinata seeds can withstand desiccation to 5% seed moisture content and freezing to –20°C indicating that seeds have orthodox seed storage behavior. Based on this information, an ex-situ collection of seeds will be stored long-term at the National Seed Storage Laboratory in Ft. Collins, CO. (Summary of Research in Progress/Completed) Genetics (Thornton, Francisco-Ortega) Seedling Demography (Pascarella) Germination (Garvue, Carrara, Griffin, Frances) Habitat Requirements (Kernan, Lane, Wright, Fidelibus) Life History/Pollination Ecology (Pinto-Torres, Koptur, Pascarella) Mapping (Kernan, Garvue, LaPuma, Thornton, Wright, Possley) Outplanting (Lippincott, Kernan, Lane, Wright, Fisher, Jayachandran) Relationship with mycorrhizae (Fisher, Jayachandran) Seed germination/biology (Wright, Maschinski) Seed Storage (Garvue, Carrara, Frances) Site history surveys (Thornton) Significance/potential for anthropogenic use: Focal species for conservation education; dune stabilization; horticultural/ ornamental use. Recovery objectives and criteria: Protection of populations: Establish new populations in protected parks with appropriate habitat within former natural range (Austin 1979, USFWS 1995). Sites must be adequately protected from further habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation; managed to maintain the coastal strand to support Jacquemontia reclinata; and monitored to demonstrate that populations of J. reclinata on these sites support the appropriate numbers of self-sustaining populations, and that those populations are stable throughout the historic range of the species. Management options: No intervention The species is in decline and is seriously threatened by coastal development pressures. Taking no action may not increase the rate of extinction if the populations already protected on public parks can be sustained. However, given the lack of observed seedling recruitment at any of the sites and the threat of extirpation of one or several of these populations due to intense fire, hurricane storm surge, or genetic drift, this species most likely requires some type of intervention to ensure its survival over the next decade. Controlled burning There are significant trade-offs to consider when thinking about controlled burning as a management option. A controlled burn can help keep habitat open and may be used to simulate a natural fire disturbance regime. Fire may be an appropriate 9 Fairchild Tropical Garden management tool for the perpetuation of the open coastal scrub habitat required by beach Jacquemontia (Lippincott 1990) As a management technique, controlled burning is also relatively low in cost. However, a controlled burn may kill individuals, and permits may be unattainable for some sites near buildings or private homes due to zoning ordinances and fire codes. The effects of fire in J. reclinata need to be tested. Outplanting Outplantings may provide corridors for gene flow via pollinators, and may also increase the numbers of populations and individuals. After the initial period of establishment, outplantings may have low maintenance requirements and may be very low in cost. Although genetic problems due to inbreeding depression may be mitigated in this way, outbreeding depression may present a new problem. Care must be taken to ensure compatibility of all introduced genetic stocks with the surrounding populations. If suitable public or private lands can be found where there is a commitment to maintenance, outplanting can be a very viable management option. Mowing and/or trimming vegetation Removal or trimming of native vegetation can reduce shading and competition with other plant species, and may be less controversial than some other techniques. Removal of vegetation, especially invasive, exotic species At some sites, invasion by exotic and weedy native vegetation is severe. Removal of invasive species can reduce competition, provide open habitat, and help other native species. Dune habitat restoration or augmentation In areas where suitable habitat already exists but could be expanded, or in places where there is an opportunity to restore a site, doing so may significantly increase the amount of habitat available for outplanting. Trail management At some sites, plants are apparently thriving alongside heavily traveled footpaths, possibly due to the decreased competition and light availability. However, plants near trails, especially seedlings and juveniles, may have difficulty surviving trampling and other disturbance. Keeping trails away from sensitive areas may serve to protect new transplants; while routing trails near older plants may provide an opportunity to increase public awareness of the species. Next steps: Exchange of information and collaboration among researchers and land managers Continue to correspond with land managers to maintain open coastal strand habitat Increasing public awareness through educational materials Continue seed germination and seedling survival experiment Conduct outplanting experiment at Sites 145 and 102 Study effect of fire on J. reclinata 10 Fairchild Tropical Garden References Austin, D.F. 1979. Endangered beach jacquemontia. In D.B. Ward, ed. Rare and Endangered Biota of Florida, Volume 5 Plants. University Presses of Florida. 175 pages. Austin, D.F., Bass, S., Honychurch, P.N. Coastal dune Plants. Gumbo Limbo Nature Center of South Palm Beach County, Inc. Boca Raton. 1991. Austin, D.F., and K. Coleman. 1977. Vegetation of southeastern Florida-II Boca Hammock. Florida Scientist. 40:331-361. Avery, G.N., and L.L. Loope. 1980. Endemic taxa in the flora of south Florida. United States National Park Service, South Florida Research Center. Everglades National Park. Report T – 558. Carrara, S. Species specific seed germination methods, storage condition trials, and cultivation notes. In: Fellows, M., J. Possley, and C. Lane. (ed.). 2001. Final Report to the Endangered Plant Advisory Council, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, FDACS Contract # 005619. Appendix C9. Carrara, S., and D. Garvue. Determine the response of J. reclinata to standard seed storage conditions. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida ecosystem. Final report to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service for grant agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173. Coile, N.C. 2000. Notes on Florida’s endangered and threatened plants. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Botany Section. Contribution No. 38. Fidelibus, M., and J. Fisher. Effect of soaking seed in fresh water and removing seed coat pigment upon germination. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida ecosystem. Final report to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service for grant agreement 1448-40181-99G-173. Fidelibus, M. and S.J. Wright. Influence of light on experimental Jacquemontia reclinata seedling growth. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida ecosystem. Final report to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service for grant agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173 Fisher, J.B. and K. Jayachandran. 2002. Arbuscual mycorrhizal fungi enhance seedling growth in two endangered plant species from South Florida. International Journal of Plant Science. 163(4): 559-566. 11 Fairchild Tropical Garden Fisher, J. Effect of light and dark on seed germination. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida ecosystem. Final report to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service for grant agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173. Griffin, K., and J. Fisher. Effects of salt water on seed germination. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida ecosystem. Final report to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service for grant agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173. Johnson, A.F., J.W. Muller and K.A. Bettinger. 1990. An assessment of Florida’s remaining coastal upland natural communities: southeast Florida. Report to Natural Areas Inventory, Tallahassee. Kernan, C. 1995. Final Report to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Project title: Jacquemontia reclinata recovery. Fairchild Tropical Garden, Coral Gables, FL. Lakela, O. and F.C. Craighead. 1965. Annotated checklist of the vascular plants of Collier, Dade, and Monroe counties, Florida. Fairchild Tropical Garden and the University of Miami Press, Botanical Laboratories of South Florida. Coral Gables, FL. Lane, C., La Puma, D., Pinto-Torres, E., Thornton, H. E. B. Final Year One Report: Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the south Florida ecosystem. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Grant Agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173. 2001. Lane, C. and S.J. Wright. Collection of vegetation and abiotic data. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida Ecosystem. Final Report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service for Grant Agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173. Lippincott C. 1990. Status Report on Jacquemontia reclinata at Hugh Taylor Birch State Recreational Area. Report to Florida Natural Areas Inventory. Fairchild Tropical Garden, Coral Gables, FL. Long, R.W. and Lakela, O. 1971. A flora of tropical Florida. University of Miami Press. Coral Gables, FL. Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, H. Thornton, J. Fisher, J. B. Pascarella, C. Lane, E. PintoTorres, and S. Carrara. 2003a. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida Ecosystem. Final Report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service for Grant Agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173. Maschinski, J., S.J. Wright, K. Wendelberger, H. Thornton, and A. Muir. 2003b. Conservation of South Florida Endangered and Threatened Flora. Final report to Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Gainesville, Florida. Contract #007182. 12 Fairchild Tropical Garden Pascarella J.B. Demography of Jacquemontia reclinata. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida Ecosystem. Final Report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service for Grant Agreement 144840181-99-G-173. Pilkey, O.H., Jr., D.C. Sharma, H.R. Wanless, L.J. Doyle, O.H. Pilkey Sr., W.J. Neal and B.L. Gruver. 1994. Living with the east Florida shore. Duke Univ. Press, Durham, NC. Pinto-Torres E. and S. Koptur. Flowering phenology and pollinator associations of Jacquemontia reclinata. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida Ecosystem. Final Report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service for Grant Agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173. Pinto-Torres, E.C. 2004. The Breeding System and Pollination Ecology of Jacquemontia reclinata (Convolvulaceae) M. S. Thesis submitted to the University Graduate School, College of Arts and Sciences, Florida International University. February 2004. Richardson, D.R. 1977. Vegetation of the Atlantic coastal ridge of Palm Beach County, Florida. Florida Scientist. 40:281-330. Robertson, K.R. 1971. A revision of the genus Jacquemontia (Convolvulaceae) in North and Central America and the West Indies. Ph.D. Dissertation, Washington University, St. Louis. 285 pages. Spier, L.P. and J.R. Snyder. 1998. Effects of Wet and Dry Season Fires on Jacquemontia curtisii, a South Florida Pine Forest Endemic. Natural Areas Journal 18:350-357. Thornton, H. 2003. Genetic variation within and among Jacquemontia reclinata populations studied. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida Ecosystem. Final Report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service for Grant Agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173. Thornton, H. 2003. Genetic Structure and Conservation of Jacquemontia reclinata, an endangered coastal species of southern Florida. M.S. Thesis submitted to the University Graduate School, College of Arts and Sciences, Florida International University. December 2003. Thornton, H. and S.J. Wright. Site-specific recommendations for management of Jacquemontia reclinata populations. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida Ecosystem. Final Report to the US Fish and Wildlife Service for Grant Agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 1994. Beach Jacquemontia. Endangered and threatened species of the Southeastern United States (The Red Book), FWS Region 4 13 Fairchild Tropical Garden United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 1995. Draft recovery plan for beach Jacquemontia (Jacquemontia reclinata). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Atlanta, Georgia. 26 pp. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 1999. Beach Jacquemontia: Jacquemontia reclinata House in South Florida Multi-Species Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Atlanta, Georgia. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 1996. Recovery plan for beach Jacquemontia (Jacquemontia reclinata). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Atlanta, Georgia. 19 pp. 14 Fairchild Tropical Garden Wright, S.J. Effects of environmental gradients within the coastal dune on survivorship of Jacquemontia reclinata outplantings. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida ecosystem. Final report to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service for grant agreement 1448-40181-99G-173 Wright, S.J. Identification of restoration sites for Jacquemontia reclinata. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida ecosystem. Final report to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service for grant agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173 Wright, S.J. Measuring the attributes of wild Jacquemontia reclinata plants. In Maschinski, J., S. J. Wright, and H. Thornton (ed.). 2003. Restoration of Jacquemontia reclinata to the South Florida ecosystem. Final report to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service for grant agreement 1448-40181-99-G-173 Wright, S.J. and M. Fidelibus. 2004. Shade limited root mass and carbohydrate reserves of the endangered beach clustervine (Jacquemontia reclinata) grown in containers. Native Plants Journal. Spring 2004 (5)1: 27-32. Wright, S.J. and H. Thornton. 2002. Summary Report of monitoring activities associated with Jacquemontia reclinata, Okenia hypogaea, and Cyperus pedunculatus at Atlantic Dunes Park, Delray Beach. Summary Report to City of Delray Beach. Wunderlin, R.P. 1998. Guide to the vascular plants of Florida. University Presses of Florida, Gainesville. 15 Fairchild Tropical Garden