Arrhythmias - The Brookside Associates

advertisement

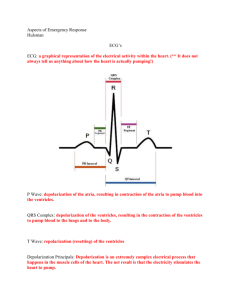

General Medical Officer (GMO) Manual: Clinical Section Arrhythmias Department of the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Peer Review Status: Internally Peer Reviewed (1) Background Cardiac rhythm disturbances are extremely common, and range in severity from the truly benign to life-threatening brady and tachydysrhythmias. The decision to treat these with antiarrhythmic agents must be made with careful consideration of the risk-benefit ratio, since the "proarrhythmic" effects of class I antiarrhythmic agents has been demonstrated to impact on management of all patient groups. Many asymptomatic patients should not be treated at all, and use of beta-blockers and calcium blocking agents should be considered wherever appropriate to minimize the risks of therapy. Alternatively in patients with life-threatening tachycardias, withholding appropriate therapy can result in tragic and avoidable complications or consequences. (2) History In patients that present during an episode of sustained cardiac dysrhythmia, the diagnosis is established through the use of the 12- lead electrocardiogram and rhythm strip; the hemodynamic consequences of the rhythm may be established by careful documentation of the vital signs (with orthostatic blood pressure where appropriate). In patients who have experienced single or repeated episodes of palpitations, the following historical data are important: (a) Frequency, duration, time of day, and positional aspects of the symptoms. (b) Whether syncope, near syncope, or dizziness accompany palpitations. (c) Association of the symptoms with use of tobacco, alcohol, or caffeine. (d) Factors that precipitate the symptoms (e.g., physical activity, emotional stress, recumbent position etc.) or have helped to terminate (valsalva, coughing) the symptoms. (e) What the heart rhythm "felt like" (it is often helpful to have the patient "tap out" the rhythm on the table). (f) Whether there is a family history of similar problems. A review of the record and history to determine what workup has been done in the past is often helpful. (3) Physical Examination The cardiac examination between episodes is often unrevealing, but palpation of the pulse and auscultation of the heart rhythm may identify frequent extrasystoles (often asymptomatic) which may provide a clue to the diagnosis. A fixed split S2 may suggest the presence of an atrial septal defect, contributing to supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) or atrial fibrillation. Various murmurs may be present to suggest contributing factors: midsystolic clicks with or without a systolic murmur suggest mitral prolapse; an ejection click and systolic ejection murmur suggest aortic valve disease; any diastolic murmur (aortic/pulmonic insufficiency or mitral/tricuspid stenosis) require cardiologic referral and evaluation. Careful documentation of the vital signs, recumbent and upright, is often helpful in determining orthostatic tachycardias. Attempts to identify other conditions which may precipitate arrhythmias (e.g., hyperthyroidism, anemia, pheochromocytoma) should be pursued where appropriate. (4) Special Tests In patients with frequent episodes of palpitations without documentation of the exact nature of the disturbance, a Holter monitor (24-hour rhythm strip) is helpful in relating symptoms to cardiac rhythm. In patients with less frequent symptoms, an event recorder or loop monitor can be provided and carried by the patient on a month by month basis. The signal-averaged electrocardiogram (ECG) is a new technique developed to assess the risk for sustained ventricular tachycardia. Echocardiography is frequently employed to rule out structural heart disease with patients who experience arrhythmias. (5) Specific Arrhythmias The differential diagnosis of palpitations should first be narrowed into two general categories: tachycardias and bradycardias. (6) Bradydysrhythmias (a) Sinus arrhythmia is a physiologic event in which the heart rate varies up to 10 percent beat to beat, with the respiratory cycle; the rhythm is irregular, and there is no clinical significance. (b) Sinus bradycardia is defined as a heart rate less than 60 beats per minute (bpm). In asymptomatic normal patients, sinus rates as low as 40 bpm are often recorded. If the blood pressure is adequate, sinus bradycardia has no clinical significance. Exercising the patient increases the heart rate appropriately. (c) Junctional rhythm often occurs in patients with healthy, slow sinus rates. The junctional rhythm will be overtaken by the sinus mechanism when the patient exercises. Junctional rhythm represents a problem when the sinus impulses are blocked (see (j.) complete heart block in this chapter) or when it appears in the face of atrial fibrillation treated with digoxin, in which it is often a digitalis-toxic rhythm. (d) Heart block represents delay in conduction in the atrioventricular (AV) node and the bundle of His; four types of AV block are generally recognized. (e) First degree block manifests a P-R interval >200 msec, and by itself has no clinical significance. (f) Second degree heart block type I (Wenchebach block) has the following characteristics: A gradually increasing P-R interval until a P wave fails to conduct. R-R intervals that shorten as the P-R interval lengthens. The P-R interval, after the dropped beat, is shorter than the last conducted P-R. (g) Wenchebach block may be "physiologic" in asymptomatic patients with high resting vagal tone; if associated with hypotension, syncope or near-syncope, therapy with atropine (.06-1.0 mg IV; repeat to a total of 2.0 mg) may be given. The patient should be referred for cardiac evaluation. When atropine relieves symptoms and hospitalization is not possible, scopolamine patches may be helpful. (h) Second degree heart block type II (Mobitz II block) has the following characteristics. P waves are dropped with no gradual prolongation in the P-R interval The QRS complexes are wide (usually there is a bundle branch block (BBB) present). (i) This is rare with normal QRS complexes. Type II block carries a high risk for development of complete heart block, and should be evaluated by a cardiologist. If symptomatic, initial therapy with atropine, 0.61.0 mg IV is indicated. Repeat to a total of 2 mg. Isoproterenol, begun at 2 micrograms/ minute and titrated slowly to a total of not more than 20 mcg/min may be used if atropine fails to provide an adequate ventricular response to achieve an adequate blood pressure (BP). If persistent, consider transcutaneous or transvenous pacing. Permanent pacing may eventually be required at the referral site. (j) Complete heart block is characterized by AV dissociation, with a junctional or idioventricular escape rhythm in which there is no association between the P waves and the QRS complexes. This should be distinguished from AV dissociation due to other mechanisms (such as accelerated junctional rhythm, in which the junctional rate is equal to or faster than the sinus rate). Such patients require referral to a cardiologist/internist. If the escape rate provides an adequate blood pressure and the patient is asymptomatic or minimally so, treatment may be deferred until the patient is hospitalized. If hypotensive or severely symptomatic, initial therapy is with atropine, 0.6-1.0 mg IV; repeat to total of 2 mg. Alternatively, isoproterenol, begun at 2 micrograms/minute and titrated slowly to a total of not more than 20 mcg/min may be used if atropine fails to provide an adequate ventricular response to achieve an adequate BP. If persistent, transcutaneous or transvenous pacing may be required as a bridge to permanent pacing. (7) Tachydysrhythmias (a) Atrial premature contractions (APCs) are ubiquitous. Isolated APCs usually have little clinical significance, except as a trigger for SVT/atrial fibrillation. They are sometimes symptomatic, but generally do not require treatment unless associated with sustained tachydysrhythmias. Therapy for symptomatic APCs is as described for VPCs below. (b) Ventricular premature contractions (VPCs) are also very common and, when seen as an isolated phenomenon, usually benign. In the absence of acute myocardial infarction, isolated VPCs do not require class I antiarrhythmic drug therapy, regardless of their frequency. When VPCs are associated with structural heart disease, their effect on patient prognosis is related to the underlying disease. When symptomatic, therapy should be a stepwise process including identification and elimination of precipitating conditions (nicotine, caffeine, alcohol or drug use, hypertension, hyperthyroidism, anemia) followed by a trial of beta blockers (atenolol, 25 mg to 100 mg/day is often used). Verapamil, 80 mg TID or Verampamil (SR), 240 mg/day may be an effective agent in some cases, particularly in those patients with “RV outflow tract originating VPCs” and non-sustained VT. If these measures fail to control symptoms, referral to cardiology is appropriate. (c) Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT) often presents with palpitations, dyspnea, lightheadedness, and/or syncope. A number of mechanisms can precipitate PSVT, but the most common are reentrant rhythms involving the AV node or accessory pathways. The rhythm is regular, QRS complexes are narrow, and P waves are often obscured (when seen, they tend to be inverted in the limb leads). Patients may often terminate PSVT with vagal maneuvers such as carotid sinus massage, valsalva, coughing, or immersion of the face in cold water. If the patient is hemodynamically unstable, with loss of consciousness, mental obtundation, or severe hypotension, the therapy is synchronized cardioversion with 50-200 joules. Most patients will be more stable and these can be treated with: Adenosine, 6-12 mg rapid IV push (this can be expected to precipitate chest pain, facial flushing, and transient high grade AV block which last for 2-3 seconds). Verapamil, 5-10 mg IV (use caution if the patient's blood pressure is marginal, pretreatment with 1/2 amp of Calcium Chloride can prevent or attenuate the hypotension that is common after calcium channel blockers). Metoprolol, 5 mg rapid IV push repeated every 5 minutes up to 15 mg. If these measures fail, the patient may be loaded with IV procainamide 15 mg/kg or 1000 mg over 45 minutes. Note: Ventricular tachycardia is often misdiagnosed as PSVT with aberrancy; it is wisest to manage wide complex tachycardias as if they are ventricular tachycardia. (d) Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is characterized by a baseline ECG in normal sinus rhythm (NSR) with a shortened P-R interval, slurring of the initial QRS complex (delta wave) and often with ST-T wave abnormalities. When WPW results in SVT, the common variety shows a normal QRS-T complex almost indistinguishable from PSVT, and so treatment should be followed as described as noted in paragraph (c). WPW may also precipitate atrial fibrillation, often with very rapid ventricular responses (see below). Patients with WPW should not be treated with maintenance dose verapamil or digoxin, regardless of the response of their PSVT to acute administration. Symptomatic patients with WPW should be treated with cardioversion or IV procainamide, and referred to a cardiologist for electrophysiologic evaluation. (e) Atrial fibrillation is usually a narrow-complex tachycardia in which the rhythm is "irregularly irregular", P waves are not consistently seen, and untreated patients typically have ventricular rates > 100 beats/minute. Occasional wide complex beats with a right bundle branch morphology are due to aberrant conduction and are called "Ashman's beats." They are not VPCs and do not imply increased risk. A very important variation is atrial fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, in which the QRS complexes will display varying wide morphologies that might be mistaken for BBB; they typically may come in "bursts" with very short R-R intervals which may precipitate ventricular tachycardia. If patients are hemodynamically unstable, direct current synchronized cardioversion with 20-200 joules is indicated. Otherwise, initial therapy in the absence of WPW is to control of the ventricular rate with IV digoxin, 0.5 mg followed by 0.25 mg every 4 to 6 hours to a total dose of 1.25 mg. IV metoprolol, 5 mg every 2 minutes up to15 mg may be used in conjunction, or verapamil, 5 to 10 mg IV. Digoxin requires 30 to 60 minutes to demonstrate an effect on the heart rate. Once the rate is controlled, conversion to sinus rhythm may occur spontaneously, but typically requires administration of a class IA antiarrhythmic drug, such as Procan SR, 500 mg po q6h, or Quinaglute 324 mg PO q6h. Patients treated with class IA antiarrhythmic agents should be in a monitored setting for at least 24-48 hours after initiation of the drugs. Administration should be stopped if the QT increases by > 50 percent in duration or if hypotension ensues. Note: Digoxin and verapamil are contraindicated in the management of atrial fibrillation with WPW, and can precipitate increases in heart rate or ventricular tachycardia. Treatment in the setting of WPW is direct current (DC) cardioversion and IV procainamide. (f) Ventricular tachycardia (VT) is defined as 3 or more VPCs in a row. It may be further subdivided into nonsustained and sustained VT. If nonsustained VT lasts less than 30 seconds, is not associated with hemodynamic compromise, and the patient has no structural heart disease, it may be managed as described above for VPCs. Patients with significant symptoms or with long runs (> 10 beats) require referral to a cardiologist. (8) Sustained Ventricular Tachycardia Sustained ventricular tachycardia is a wide complex regular rhythm with a rate > 110 bpm which often presents with chest pain, dyspnea, heart failure, lightheadedness, or syncope. AV dissociation may or may not be present (50 percent of cases). Treatment for hemodynamically unstable VT is synchronized DC cardioversion with 50-360 joules. In patients with hemodynamically tolerated VT, an alternative is loading with either of the following: (a) IV lidocaine, 1.5 mg/kg pushed over 2 minutes and followed by a 2 mg/min drip with a second bolus of 1 mg/kg in 20 minutes or (b) Procainamide, 15 mg/kg or 1000 mg over 30 to 40 minutes, followed by a 2 mg/min drip. Use caution when loading with procainamide, as prolongation of the QT > 50 percent (or Qtc greater than 0.47) from the baseline mandates holding the drug and suggests a risk of development of heart block. Excessive QT prolongation from administration of procainamide (or any type IA drug) may precipitate Torsades de Pointes. Loading with antiarrhythmic drugs requires continuous ECG monitoring, preferably for 48-72 hours. Administration of empiric antiarrhythmic drugs for the long-term management of either sustained or nonsustained VT has been associated with a 25-200 percent excess arrhythmic mortality and is to be discouraged. Patients with sustained VT or symptomatic nonsustained VT unresponsive to beta-blocker therapy should be referred for cardiologic/electrophysiologic evaluation. Reviewed by CAPT K. F. Strosahl, MC, USN, Cardiology/Computer Assisted Program of Cardiology Specialty Leader, Cardiovascular Disease Division, Portsmouth Naval Hospital, Portsmouth, VA (1999).