Aspectual Decomposition and the Durative Phrases

advertisement

Liao, Wei-wen

Aspectual Structure and the Syntax of Chinese Durative Phrases

Liao, Wei-wen

lwwroger@ms48.hinet.net

1. Introduction

This article inspects the aspectual structure and the durative phrases in Chinese. I propose

that aspect should be decomposed into three layers of representations, an approach that I call

the Three-layerd Aspectual Structure (henceforth, TAS). I show that Chinese provides

strong evidence for such a claim. First of all, each of the three aspectual layers in syntax is

morphologically realized in Chinese. Second, the durative phrases in Chinese can be

interpreted in three distinct ways, thus corresponding to the three aspectual layers.

Section 2 reviews the theories of aspect by Reichanbach (1947) (supplemented by

Hornstein 1990), Smith (1991), and Klein (1994). I conclude that aspect should be

decomposed into three levels of representations. The first (also the lowest) level is the

lexico-compositional aspect, the information of which is provided by the inherent properties

of main verbs and their combinations with other lower predicates. The second level is the

viewpoint aspect, where the internal structure of the lexico-compositional aspect is viewed

from a certain viewpoint, or the topic time in the sense of Klein (1994). The two levels (in the

lexical cycle) combined together and give an aspectual complex. The complex is sent to the

third (highest) level, the temporal aspect, which is functional and tense-related. The aspectual

complex is then punctualized into a point, called event point. The aspect in this level arises

from the relative position between an event point and a reference point in the sense of

Reichanbach (1947).

Section 3 provides supporting evidence for TAS: the interpretations of the durative

phrases in Chinese. Liao (2004) points out that the durative phrases in Chinese can have three

kinds of interpretations: the Target State-related reading (TS-related, measuring the target

state), the Process-related reading (P-related, measuring the process), and the Reference

Time-related reading (RT-related, measuring the time from a given point to the reference time,

see below). I argue that the three interpretations correspond to three aspectual levels,

respectively. The following three examples illustrate these three readings:

(1)

a.. Zhangsan da-kai

chuanghu san-ge xiaoshi.

ZS

hit-open window three-Cl. hour

‘ZS opened the window for three hours.’

[TS-related]

b. Zhangsan du-le

zhe-ben shu san-ge xiaoshi

ZS

read-LE this-Cl. book three-Cl hour

‘ZS [kept] reading the book for three hours.’

[P-related]

c. Zhangsan gai-wan

zhe-dong

fangzi san-tian le.

ZS

build-finish this-Cl.

house three-day LE

‘It has been three days since ZS built the house.’

[RT-related]

Notice that in the RT-related reading, in the case of (1c), the durative phrase measures the

1

Liao, Wei-wen

time span from the end of an event to a reference point. Such an aspect has rarely been

discussed.1

In section 4, the proposal is laid that the three readings of the durative phrases reflect the

three aspectual layers in syntax in a one-to-one fashion. In the TS-related reading, the

durative phrase modifies the target state projections (from the lexico-compositional level).

The durative phrase of the P-related reading modifies the aspectual projection in the

viewpoint level, which is headed by Chinese verbal-le. The durative phrase of the RT-related

reading modifies the temporal aspect level, which is headed by the sentence final particle le

(SFP le). I show that the structure of the durative phrases is closely related to the aspectual

structure in Chinese.

Section 5 discusses the theoretical consequences of the proposed analysis. Semantically,

the analysis can account for the telicity issue (see 2, 3), and syntactically, it explains why the

durative phrases seem to be exceptions of the rightward convention of Chinese adjuncts:

(2)

(3)

??John ate the hamburger for three hours.

Zhansan chi-le zhe-ge hanbao

san-ge

ZS

eat-LE this-Cl. hamburger three-Cl.

‘ZS ate the hamburger for three hours.’

[marginal in English]

xiaoshi.

hour

[perfect in Chinese]

2. The Three-layered Aspectual Structure Hypothesis

In this section I first review the relevant theory of aspect (section 2.1), and then propose

the Three-layered Aspectual System (TAS) (section 2.2).

2.1 Theories of Aspect

2.1.1 Aspect as Tense: Reichanbach (1947); Hornstein (1990)

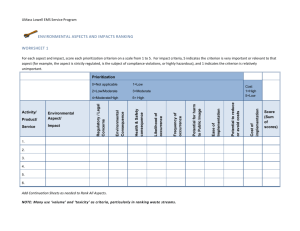

Reichanbach (1947) regards aspect as a part of the Basic Tense System, as in (4):

(4)

R

Tense

Aspect

S

E

(R for reference time; S for situation time; E for event time)

Three possible combinations can be found, plus three aspect relations, shown as follows:

The term Target state is adopted from Parsons (1990), and is meant to be equivalent to ‘result state’ in Piñón’s

sense.

1

2

Liao, Wei-wen

(5)

the construction of tenses and aspects

TENSE

R,S / S,R

present

E,R / E,R

R_S

past

R_E

S_R

future

E_R

ASPECT

simple

prospective

perfect

One problem with this theory is its weakness in describing the variety of aspectual

patterns. For instance, the theory of Reichanbach does not provide a powerful enough

mechanism in differentiating perfect and perfective, but the difference between the two

aspects is obvious (Chung and Timberlake 1985; Binnick 1991; Smith 1991). Perfect aspect

is reference time-related, while the perfective aspect is not necessarily so. The perfective

aspect concerns the completion of the event regardless of any reference time. Furthermore,

aspect in different languages is more capricious than Reichanbach’s theory had expected.

Consider the following Chinese examples. Different aspectual values (completive in (6a) and

perfective in (6b)) fall into the same temporal structure, as in (7):

(6)

a.

b.

(7)

Ta jintian zaoshang du-wan na-ben shu.

[completive; -wan]

he today

morning read-finish that-Cl book

‘He finished reading that book this morning.’

Ta jintian zaoshang du-le

na-ben shu.

[perfective; -le]

he today

morning read-LE that-Cl book

‘He read that book this morning (regardless of the completion).’

E, R _ S

this morning

E, R _ S

this morning

2.1.2 Two Parameters of Aspect: Smith (1991)

Smith (1991) proposes that aspect is conditioned by two parameters. One parameter is

speakers’ viewpoint of the situation, and the other is the situation types.

Aspect then characterizes the way how the speaker views the internal structure of the

situation, which consists of the interval (where it takes place) and the two endpoints,

including an initial point (SI) and a final point (SF) (S stands for the situation). Depending on

whether SI or SF is viewed by the speaker, the aspectual viewpoints are of three categories:

(8)

The Viewpoint Categories in Smith (1991)

+SI, +SF

perfective

+SI, –SF

neutral

–SI, –SF

imperfective

3

Liao, Wei-wen

The other parameter of aspect is the situation types. The situation types characterize the

inherent temporal/aspectual information in the lexicon. Smith distinguishes situations into

five prototypes, including State, Activity, Accomplishment, Achievement, and Semelfactive

(see Smith 1991 for details). According to Smith (1991), a situation is located in a time

interval with a given viewpoint superimposed on it, and in this manner aspect is composed by

these two parameters.

Nevertheless, Smith’s theory has a theory-internal problem. If both the viewpoint and

situation type have their independent time intervals, it seems that the time interval of the

situation loses its function when combined with the viewpoint. For example, in the

imperfective aspect, neither SI nor SF of the viewpoint plays any role; therefore, in

propositions like [John RUN], or [John SING A SONG], although the initial point provided

by the situation appears, the same initial point loses its function when the situation is

combined with the imperfective viewpoint (–SI, –SF). In a nutshell, the ontological basis for

the time interval of the situation appears dubious (see Klein 1994 for a detailed critique on

the formal notions Smith has adopted).

2.1.3 Tense-related Analysis of Aspect: Klein (1994)

Klein (1994) argues for a time-related analysis for tense and aspect. He proposes three

primitives for the temporal structure, the utterance time (TU), the situation time (TSit) and

the topic time (TT). TT differs from the Reference Point in Reichanbach’s (1947) system in

that TT has a complicated internal structure. Aspect in this theory characterizes how TSit is

linked to a certain TT.

Klein also employs a novel way to characterize the situation types. He regards situation

types as lexical contents of three kinds: 0-phase, 1-phase, and 2-phase lexical contents (in the

terms of Klein et al. 2000).

Klein’s approach enriches the lexical content and reconciles the inconsistency between

situation types and viewpoints. However, his effort to unify the perfect and perfective aspect

in the same time axis is not without problem. Consider the examples in (9) and the temporal

representations in (10). According to Klein, TT provides the only accessible information for

aspectual marking. Therefore, the durative phrase in (10a) arguably measures the topic time,

which is the same as TSit in this case. On the other hand, in (10b) the durative phrase

measures the duration of the TSit, which is outside the TT, and should not include aspectual

information, given the premise of TT. In Klein’s approach, it should be possible to represent

the duration of the topic time in the perfect aspect, but this is contrary to the fact, as in (10b’):

(9)

a. John swam for ten minutes.

b. John has swum for ten minutes.

(10) a.

[perfective]

[perfect]

[++++++++++]

pretime {

TSit

}

10 min.

4

posttime

Liao, Wei-wen

b.

++++++++++

pretime {

TSit

}

10 min.

b’ *

++++++++++

pretime {

TSit

}

[ ]

posttime

[

]

posttime

10 min.

Furthermore, if we assume the durative phrase only measures the TSit, as Klein himself

claims, then we cannot account for the fact that in the RT-related reading, the durative phrase

measures the post-event time (hence outside TSit), such as (1c).

2.2 Three-Layered Aspectual Structure

I propose a dynamic theory of aspect in this work, which I call the Three-layered Aspectual

Structure (TAS). That is, aspect is actually a composite of information from three

independent levels. This way, we can solve the incongruity between Reichanbach’s, Smith’s,

and Klein’s theories. The three levels are as follows.

The first level is the lexico-composition level. This level corresponds to the

conventional notion of lexical aspect or aktionsart. The aspectual resource in this level is the

lexical features. Theoretically speaking, this level provides the prototype of the lexical

information, corresponding to the lexical content in Klein’s sense.

The second level is the viewpoint level, corresponding to the conventional notion of

grammatical aspect, or aspectual viewpoint. The aspectual information provides a topic time

onto the lexical content in the first level, resulting in a specific viewpoint. This aspect

corresponds to aspect in Klein’s sense.

The third level is the temporal aspect. The aspect of this level arises from the interaction

between a given reference point and a condensed event point (including TT and lexical

content). This level of aspect is best understood with the Reichanbachian approach. The

general frame of TAS looks as follows:

(11) Three-layered aspectual system (TAS)

basis for observation

compositional aspect

lexical features and

their composition

viewpoint aspect

topic time

temporal aspect

reference point

5

classifications

[± change]/[ADD TO]

([± telic])

perfective

neutral

imperfective (incl.

progressive & habitual)

simple

perfect

prospective

Liao, Wei-wen

The interaction between the three layers is not rigid and may be subject to specific

language strategies in aspectual representation. Consider the perfective aspect in English.

English is a language without explicit perfective markers. However, the concept of

perfectivity is represented by means of the other two levels (past simple tense plus

accomplishment), as in (12). On the other hand, the past-simple-accomplishment equivalent

in Chinese does not necessarily represent a perfective viewpoint, as in (13a). The perfective

aspect in Chinese usually comes along with a completive verbal marker, as in (13b), or a

secondary predicate, as in (13c) (Smith 1991; Kang 1999; Klein et al. 2000 among others):

(12) John ate a hamburger, (*and he is still eating it).

(13) a. Zhangsan hua-le

yi-fu hua,

dao

xianzai hai hua-zhe.

ZS

draw-LE one-Cl picture until now

still paint-Prog.

‘(literally:) ZS painted a picture, and he is still painting it.’

b. Zhangsan chi-wan yi-ge hanbao.

ZS

eat-finish one-Cl hamburger

‘ZS ate a hamburger.’

c. Zhangsan ba panzi chi-de ganganjingjing.

ZS

BA dish eat-DE clean

‘ZS ate the dishes completely.’

A similar proposal is made by Tenny (2000). She suggests that aspect be represented in three

levels in the syntactic structure. Her evidence comes from the concept of core event and the

behaviors of adverbial modifications. The big picture hence looks like the following (from

Tenny 2000: 326 with modification):

(14)

PoVP

Point of view

TP

Functional cycle

Tense

…

h-AspP

Higher aspect

temporal level

VP1

V1

Lexical cycle

m-AspP

Middle aspect

viewpoint level

VP2

V2

root

(Inner aspect) composition level

6

Liao, Wei-wen

My proposal, from a different line of reasoning, matches her proposal with a striking

similarity. That is, inner aspect corresponds to the composition level, middle aspect to the

viewpoint level, and higher aspect to the temporal level.

Note that in both proposals, aspect is laid out to different projections, contra the received

view, which assumes that aspect is represented by a single projection, say, AspP (Cheng

1991). This proposal also claims that aspect is dynamically built from bottom to the top. In

this fashion, the proposal is reduced to Strict Cycle Condition. In Chomsky (2001), the strict

cycles (or phases) are taken to be CP and vP. CP as a phase introduces the sentence-level

operators. vP is the projection in which all lexical requirements are satisfied. Turning back to

TAS, while the compositional level and the viewpoint level are closely tied, little interaction

is found between the temporal level and the other two levels. In Chinese, the first two levels

can be combined together with the similar type of verbal morphology (verb-le and RVC can

co-exist, e.g. chi-wan-le ‘eat-finish-LE’), but the temporal level is represented by the

sentence-final particles, such as SFP le, a distinct morphological mechanism (I will return to

this point later). The strict cyclicity of the TAS, thus, is derived from phases (assumed as the

important property of derivation). This may be regarded as a theory-internal support for the

syntax of TAS, though many technical details still need elaborating. I will leave it to further

study.

Empirical evidence can also be found, which comes from the different interpretations of

the Chinese durative phrases, a point I will discuss in the next section.

3

The Interpretations of the Durative Phrases in Chinese

3.1 Three Kinds of Durative Phrases

In addition to the two kinds of readings of durative phrases proposed in Li (1987) and Lin

(2003a), Liao (2004) suggests that there are actually three kinds of readings for the Chinese

durative phrases: the Target State-related reading (TS-related), the Process-related reading

(P-related), and the Reference Time-related reading (RT-related) (for expository convenience,

I assume readers’ familiarity with Klein’s and Reichanbachian notations) (< > stands for the

measured time span):

(15) TS-related (target state)

a. Zhangsan ba chuanghu

tui-kai

san-ge xiaoshi.

ZS

BA window

push-open

three-Cl. hour

‘ZS opened the window for three hours.’

b.

– – – – – – – [+ + + + + + ]

pre-opening { opening } post-opening

<

> three hours

7

Liao, Wei-wen

(16) P-related (process)

a. Zhangsan zhe-ben shu

du-le

liang-ge xiaoshi.

ZS

this-Cl. book

read-LE two-Cl. hour

‘ZS read this book for two hours, (whether he finished or not.)’

b.

[– – – – ]– – – ] + + + + + + …

pre-reading {

reading } post-reading

<

> or > two hours

(17) RT-related (reference time)

a. Zhangsan du-wan

shu

san-tian le.

ZS

read-finish

book

three-day LE

‘It has been three days since ZS read this book.’

b. E ____ R , S

< > three days

Specifically, Liao (2004) draws a distinction between the two post-event durative

phrases, namely, TS-related and RT-related. The TS-related durative phrase measures the time

span of the target state in the sense of Parsons (1990), and the RT-related durative phrase

measures the time span from the condensed event point to the reference point.

As far as TAS is concerned, the TS-related reading corresponds to the

lexico-compositional aspect. This is evidenced by the fact that the TS-related reading

emerges in the sentence with a target state, which is generated by a secondary predicate or a

resultative verbal compound (RVC) in Chinese (corresponding to English [in-the-water] and

[open] types in Piñón 1999). Therefore, in the case of opening the window in (15), the target

state is the window being (resultatively) open (the window can be closed again). On the other

hand, in cases such as [x swim] and [x love y], there exist no target states, and hence the

TS-related reading is not possible. This indicates that the aspectual properties in this level

crucially depend on the properties of individual lexical items and their composition.

The durative phrase of the P-related reading appears in the viewpoint aspect level. The

P-related reading tells the time from the initial point to the final point (either arbitrary or

natural), which in Chinese syntax is brought about by the aspectual marker, verbal -le, the

detail of which is discussed in the next subsection.

The durative phrase of the RT-related reading occurs in the temporal aspect level since

the durative phrases measures the time span with respect to a reference point, as I have shown

in (17). The reference point is introduced by the perfect aspect (in Chinese, the SFP le), and

there are three possible time spans for measurement: the ongoing event, the target state, and

the resultant state, as in (18)-(20), respectively:

(18) Zhangsan da-kai

chuanghu san-tian le.

[target state --> RT]

ZS

DO-open window three-day LE

‘It has been three days since ZS opened the window.’

8

Liao, Wei-wen

(19) Zhangsan

pao-le san-tian

le.

[ongoing event --> RT]

ZS

run-LE three-day

LE.

‘It has been three days since ZS started running.’

(20) Zhangsan

xie-wan

zuoye

san-tian le. [resultant state --> RT]

ZS

write-finish homework three-day LE

‘It has been three days since ZS finished writing his homework.’

Note that there are differences between (15) and (18), or between (16) and (19). (15) and (16)

show closed process and target state (which is over), while (18) and (19) show open process

and target state (which is not yet over). Theoretically, it is not possible to measure an open

state. However, owing to the introduction of a reference point (which stands as an final point

for measurement), it is therefore possible to measure part of the ongoing state and part of the

target state, and the open resultant state, all subsumed under the RT-related reading.

3.2 Evidence from Chinese Aspectual Markers

Evidence for TAS comes from the interaction between aspectual markers and the durative

phrases in Chinese: the lexico-compositional aspect is realized by the resultative verb

compound (RVC) or a secondary predicate, as in (21). The viewpoint aspect can be

represented by the aspect marker verbal -le, as in (22), and the temporal aspect by the SFP le,

as in (23):

(21) a. Zhangsan ba chuanghu da-kai.

[RVC]

ZS

BA window

DO-open

‘ZS opened the window.’

b. Zhangsan tiao jin shui-li.

[secondary predicate]

ZS

jump into water-(in)

‘ZS jumped into the water.’

(22) Zhangsan xie-le

zuoye.

ZS

write-LE homework

‘ZS wrote his homework.’

[verbal -le]

(23) Zhangsan xie

zuoye

le.

ZS

write homework LE

‘ZS has finished writing his homework.’

[sentence-le]

I assume that verbal -le denotes the ‘realization’ aspect (Liu 1988), while the SFP le

denotes the perfect aspect (since the main function is to introduce a reference time).

In the viewpoint aspect level, verbal -le only specifies the initial point of the situation

(this is an interpretation of Liu’s (1988) on Smith’s theory). On the other hand, the final point

of the situation, though unspecified, is bound only by implicatures (which is cancelable).

Therefore, the realization aspect in Chinese differs from the perfective aspect in English in

9

Liao, Wei-wen

the specification of the final point. This is why the Chinese sentences (24a,b) are grammatical,

while the English equivalents (24c,d)are awkward (cf. Smith 1991):

(24) a. Zhangsan zuotian

du-le

yi-ben shu,

keshi meidu-wan.

ZS

yesterday read-LE one-Cl. book,

but not read-finish

‘ZS read a book yesterday, but he did not finish reading it.’

b. Zhangsan gai-le

yi-dong fangzi, keshi mei gai-wan.

ZS

buile-LE one-Cl. house, but not build-finish

‘ZS built a house, but he didn’t finish builing it.’

c. *John read a book, but did not finish reading it.

d. *John built a house, but did not finish building it.

As to the temporal aspect level, the SFP le as a perfect marker introduces a reference

point to the temporal-aspectual structure. The contrasts between (25a) and (25b) well

illustrate this point. A given reference point ‘1492’ is introduced in (25b), while in (25a)

‘1492’ is the event time (as well as the reference point):

(25) a.

1492 nian, Gelunbu

faxian-le

xin-dalu.

1492 year Columbus discover-LE new-continent

‘In 1492, Columbus discovered the new continent.’

b. #1492 nian, Gelunbu

faxian

xin-dalu

le.

#1492 year Columbus discover new-continent LE

‘In 1492, Columbus had discovered the new continent.’ (Contrary to the fact)

4 The Syntax of Aspect and the Durative Phrases

This section discusses how Chinese aspect and durative phrases are represented in syntax.

From the distributions of the two le’s, the TS-related reading is possible without either le’s,

the P-related reading is usually accompanied by the verbal -le, and the RT-related reading

must be accompanied by the SFP le, as in (15) to (17). It is a prerequisite to understand the

syntax of the two le’s (section 4.1) before we understand the syntax of the durative phrases

(section 4.2).

4.1 The Structure of Chinese Aspect

The question of Chinese le’s has raised many controversies (see Cheng 1990, Sybesma 1997,

1999, and Jowang Lin 2000, 2003b). For conciseness, I assume the framework of light verb

syntax of Lin (2001), who proposes that Chinese light verbs function semantically as

eventuality predicates, such as CAUSE, BECOME, etc. The verb-le, in the spirit of this

framework, contributes the REALIZE eventuality to the main predicate. The structure in Lin

(2001) is as follows (with simplification):

10

Liao, Wei-wen

(26)

vP

v

argument-selecting light verb

vP

aspectual light verb = viewpoint aspect

v

VP

V

matrix verb

secondary

predicate

VP

Verbal -le and other aspectual markers, –zhe (progressive) and –guo (experiential), are

treated as the head of the (viewpoint) aspectual light verb. The lexical verb is base-generated

in the matrix V, and a series of head movements lead to the surface form. See (27):

(27) a. Ta xie-wan-le

zhe-feng xin.

he write-finish-LE this-Cl letter

‘He wrote the letter.’

b.

vP

DP

zhe-feng xin

‘this letter’

v'

v

vP

le

VP

V

|

xie

‘write’

VP

|

wan

‘finish’

This analysis matches TAS in a nice way. Notice that the lexical content is linked to a TT, as

is proposed by Klein (1994). I suggest that the syntactic mechanism responsible for this

linking to TT is the V-to-v head movement.

As for the SFP le, Shen (2004) notes that in a Chinese sentence, the predicate and the

sentence final particle must agree in aspectuality (dynamic vs. static). Therefore, the SFP le

matches a dynamic light verb, and another sentence final particle (SFP ne) a static one. The

SFP-le heads the AspP in the temporal aspect of TAS. I assume that the dynamic feature in

Asp0 (a kind of generalized EPP-feature in the sense of Chomsky 2001) drives the movement

of the whole complement (which is vP) to the Spec of AspP for checking purpose, as in (28)

(see also Shen 2004 for similar syntactic mechanism):

11

Liao, Wei-wen

(28)

AspP

vPi

Spec

Asp'

v'

v

|

[+Dyn]

VP

Asp

|

le

|

[+Dyn]

ti

As Tzong-hong Lin (p.c.) points out, there is empirical evidence for this claim from the CED

effect (Huang 1982). Assume Tsai’s (1994) theory of A'-dependencies.2 Adverbial

wh-phrases in Chinese must move at LF to [Spec, CP]. As expected, the adverbial wh-phrase

zenme ‘how’ cannot move out of the vP if the sentence contains the SFP le (see 29). This

indicates that the vP has indeed moved across the SFP le to the Spec position, hence inducing

a CED violation:

(29) a. Laowang [zenme

zhu niurou] (*le)?

Laowang .how(manner) cook beef

LE

‘How did Laowang cook the beef?’

b. Zhangsan

[zenme chi-wan-le

hanbao]

(*le)?

ZS .

how

eat-finish-LE hamburger LE

‘How did ZS eat the hamburger?’

To sum up, the lexico-compositional aspect shows different lexical contents, represented

in Chinese by the main verb, its composition with the secondary predicate or the RVC

construction. The viewpoint aspect is represented by the verbal -le (and -guo, -zhe), the

function of which is to link the lexical content to a given viewpoint, forming an aspectual

complex of TT and situation. Syntactically, the linking is achieved through head movement.

The highest temporal aspect is represented by the sentence final particles, such as SFP le.

Semantically, it condenses the aspectual complex to a point, and then linked it to a reference

point. Syntactically, the complement of the AspP (i.e. vP) raises to [Spec, AspP] for

dynamicity checking.

In the next section, I discuss the placement of Chinese durative phrases in the structure

of TAS.

2

There is another consequence in Tasi’s (1994) proposal. That is, Subjacency and CED also apply at LF,

contrary to the original proposal in Huang (1982).

12

Liao, Wei-wen

4.2 The Structure of the Chinese Durative Phrases

Consider first the durative phrases of TS-related reading. I have argued that the

TS-related reading requires a target state in the sentence. According to the source of the target

state (by RVC or by a secondary predicate), two structures involved in the TS-related durative

phrases are shown in (30) and (31):

(30) a. ta da-kai

chuanghu wu-fenzhong.

he do-open window five-minute

‘He opened the window for five minutes.’

b.

vP

v

vP

v

|

da

[DO]

VP

NP

wu-fenzhong

‘five-minute’

V

|

kai

‘open’

Following Hale and Keyser (1993, 1997, 2002), the resultative verb (kai in (30)) is

base-generated in the root position. I propose that the durative phrase of the TS-related

reading is in the Spec position of the root phrase or the secondary predicate, modifying the

time span of the target state.3 In (31), the target state is brought about by the secondary

predicate VP jin shui-li ‘into the water’, and it is this target state that is modified by the

durative phrase:

(31) a. ta tiao jin

shui-li

wu-fenzhong.

he jump into water-in

five-minute

‘He jumped into the water for five minutes.’

3

The subject position of the secondary predicate is omitted in this discussion. Actually, this is an issue that

deserves a serious argumentation. For simplicity, I assume the generalized control approach in Huang (1984). In

(34b), this leaves a Pro (bound by the object) in the subject position of the secondary predicate, to which the

adjectival head attribute its property. Another possibility to consider this structure is that X' (X= P or A) itself

undergoes reanalysis, as in Larson (1998), and move as a head, as illustrated in (31b).

13

Liao, Wei-wen

b.

VP

V

VP

V

|

tiao

‘jump’

VP

NP

VP [V reanalysis]

wu-fenzhong

‘five-minute’

V

|

jin

‘into’

PP

|

shui-li

‘water-in’

Second, since the P-related reading is closely related to the verbal –le in the viewpoint

level, the structure looks like (32). The durative phrase modifies the projection of the vP:

(32) a. Zhangsan [vP xie-le

zhe-feng xin

san-tian].

ZS

write-LE this-Cl

letter three-day

‘ZS wrote the letter for three days.’

b.

vP

DP

zhe-feng xin

‘this letter’

v'

v

|

Xiej-lei

‘write’

vP

NP

san-tian

‘three day’

c. *Zhangsan

ZS

xie-wan-le

write-finish-LE

vP

v

|

‘ti

VP

|

tj

zhe-feng xin

this-Cl

letter

san-tian.

three-day

One piece of evidence for this structure comes from the homogenous requirement (Moltmann

1991). Notice that the durative modification is illicit when the verb chunk is not homogenous.

In (32), the process xie-le is homogeneous and can be modified by the durative phrase.

However, another verb chunk xie-wan-le ‘write-finish-LE’ (32c) will be ruled out in presence

of a durative adverb, since the result is not homogeneous.

As to the RT-related reading, since the reference point is provided by the SFP le, I

assume that the durative phrase modifies the AspP in the RT-related reading (see 33):

14

Liao, Wei-wen

(33)

ta da-kai

chuanghu wu-fenzhong le.

he do-open window five-minute

LE

‘It has been five minutes since he opened the window.’

AspP

vPi

Spec

AspP

v'

NP

AspP

…

v

Asp

|

da-kai chuanghu

wu-fenzhong le

‘open the window’ ‘five minute’

ti

One piece of empirical evidence comes from negative and modal scope. In Chinese, one

can negate the main predicate by inserting the negation mei-you ‘not-have’ before the

predicate. We can see that both of the TS-related and the P-related readings are negated along

with the predicate. This indicates that the TS-releated and the P-related readings are

predicate-internal (see 34a,b). On the other hand, the durative phrase of the RT-related

reading is immune from the negation (see 35). This suggests that the durative phrase of the

RT-related reading is outside the scope of the negation and is generated out of the main

predicate:

(34) a. Zhangsan mei-you da-kai

chuanghu hen-jiu.

ZS

not-have DO-open window very-long

‘ZS did not open the window for a long time.’

b. Zhangsan mei-you chi hen-jiu.

ZS

not-have eat very-long

‘ZS did not eat for a long time.’

c. Zhangsan mei-you zhe-yang zuo

hen-jiu

le

ZS

not-have this-way

do

very-long

LE

‘It has been long since ZS did so last time.’

(35)

The RT-related durative phrases: immune from negation

AspP

NegP

Neg

AspP

vP

…

RT-Dur.

AspP

Asp

t

15

Liao, Wei-wen

Consider the modal scope next. Assume that ModalP is base-generated above AspP. The

fact that the modal scope covers the RT-related reading, as in (36), indicates that the durative

phrase of the RT-related reading is generated lower than the ModP but higher than the NegP.

This leaves the AspP as the only possible site (see 37):

(36) a. Zhangsan dagai

du

daxue wu-nian-duo

le.

ZS

probably read college five-year-more LE

‘ZS probably have studied in college for more than five years.’

b. Zhangsan keneng

yong zuo-shou xie zi

henjiu

le.

ZS

likely

use

left-hand write word very-long LE

‘It is likely that ZS can use his left hand to write for a long time.’

(37) The RT-related durative: subsumed to the Modal scope:

ModP

Subj

Mod'

Mod

AspP

vP

AspP

…NegP

RT-Dur

5

Consequences and Remarks

Here I would like to discuss some questions pertaining to the differences between Chinese

and English with respect to aspect and durative phrases.

The first question is about the telicity. An asymmetry exists between Chinese and

English telic expressions: The telic sentences in Chinese allow, while in English reject, the

existence of a durative phrase of the P-related reading:

(38) a. ??John ate the hamburger for three hours.

b. Zhansan chi-le zhe-ge hanbao

san-ge

xiaoshi.

ZS

eat-LE this-Cl. hamburger three-Cl. hour

‘ZS ate the hamburger for three hours.’

Under the proposed theory, this asymmetry can be accounted for in a straightforward manner.

The verbal -le denotes a realization aspect (Liu 1988), which specifies only the initial point.

That is, verbal -le does not concern the natural final point; on the other hand, an arbitrary

final point of the situation is introduced by default (as in the case of activities). This arbitrary

final point allows the events to be activity-like. The same logic applies to English

16

Liao, Wei-wen

accomplishments as well. In English an arbitrary final point of the situation is introduced by

contexts or by other syntactic means (e.g. durative preposing). Owning to the arbitrariness,

the ‘lexically’ telic event may become atelic: accomplishments become activities. This is

evidenced by the following sentence, which is lexically telic, but turns out to be atelic due to

durative preposing:

(39) For three hours, John ate the hamburger.4

a. ‘John brought about the event that the eating of the hamburger lasts for three

hours.’

b. *‘John naturally entered the state that the hamburger was eaten for three hours.’

In (39a) an arbitrary final point is introduced, and the sentence characterizes the arbitrariness

of John’s eating the hamburger intentionally (or forcedly) for three hours (Verkuyl calls it

‘forced reading’). The interpretation in (39b) sounds bizarre since the arbitrary final point has

replaced the natural final point, and this is why the accomplishment flavor of this sentence is

dropped.

The second question concerns why the durative phrases (as adjuncts) occupy the

exceptional rightward position in Chinese, unlike other conventional adjuncts which appear

leftward in Chinese (cf. Tang 1990; Lin and Liao 2003). For example, locative, temporal

(both deictic and anaphoric), and manner adverbs are instances of left adjuncts. Assume they

are IP/vP-level (Bowers 1993; Tang 1990). The structure hence looks like (40a) and (40b).

CP-level adjuncts are also left adjuncts, such as (40c):

(40) a. Zhangsan [vP zai jia-li

[v' kan

dianshi]].

ZS

in home-in

watch TV

‘ZS is watching TV at home.’

b. Zhangsan [IP mingtian [I' zai jia-li

xie

baogao.]]

ZS

tomorrow

in home-in write paper

‘ZS is going to write his paper tomorrow.’

c. [CP cong jintian-qi, [C' Zhangsan shi boshi le.]

from today-on

ZS

BE PhD

LE

‘From today on, ZS is a Ph.D.’

Given the conventional directionality of adjuncts, how can we explain the unusual behaviors

of the durative phrases? Under the proposed theory, the surface ordering is actually derived

from series of movements, and the durative phrases are stranded in the sentence-final position.

Thus, the structures have the general shape, as in (41):

4

Higginbotham (1994) suggests that a sentence such as ‘I had my wallet stolen’ may have three readings:

a. ‘I came near to suffering the theft of my wallet.’

b. ‘I was on the point of engineering the theft of my own wallet.’

c. ‘I was on the point of being in a position where I would be certain of stealing my own wallet.’ (filtered

out by context).

I pursue his idea here, and generalize it to the accomplishements with the durative phrases.

17

Liao, Wei-wen

(41) [YP…X0/XPi…RT-Dur…Y [ZP…P-/TS-Dur…ti …]]

To recapitulate, in the TS-related reading, YP=VP, and ZP=the resultative phrase, which

moves up to VP and leaves the durative phrase stranded rightward to the main predicate. In

the P-related reading, the YP=vP, and X0=V0, which adjoins to v0. In the RT-related reading,

the durative phrase appears in YP domain, and XP=vP, which raises to spec of YP. As we can

see, the surface rightward adjuncts are actually stranded rather than base-generated. Therefore,

the uniform directionality of adjunct still holds in the proposed theory.

The last question is to examine the co-occurrence of the different readings of the

durative phrases. Consider the following sentences:

(42) a. *Zhangsan kai-le chuanghu wu-fenzhong wu-tian yi-ge-yue

le.

ZS

open-LE window five-minute five-day one-Cl-month LE

(P-related, TS-related, and RT-related)

b. *Zhangsan

kai-le

chuanghu wu-tian yi-ge-yue

le.

ZS

open-LE window five-day one-Cl-month LE

(TS-related and RT-related)

c. *Zhangsan

kai-le

chuanghu wu-fenzhong wu-tian.

ZS

open-LE window five-minute five-day

(P-related and TS-related)

d. *Zhangsan kai-le

chuanghu wu-fenzhong yi-ge-yue

le.

ZS

open-LE window

five-minute one-Cl-month LE

(P-related and RT-related)

All of the combinations of the TS-related, the P-related, and the RT-related above show the

co-occurrence restriction. However, the grammatical sentences like the following can still be

found, where the main predicate is in habitual aspect (with adverbial meitian ‘every day’):

(43) a. Zhangsan meitian

pao ban-xiaoshi san-nian

le.

ZS

everyday run half-hour

three-year LE

‘For three years, ZS has been running for half hour every day.’

(P-related and RT-related)

b. Zhangsan meitian

kai

chuanghu wu-fenzhong san-nian le.

ZS

everyday open window five-minute three-year LE

‘For three years, ZS has opened the window for five minutes every day.’

(TS-related and RT-related)

Notice that (43 a-b) are in the habitual aspect, and the habitual aspect allows the durative

phrases to modify the homogenous state, which is the habitual states per se. Therefore, in the

grammatical sentences, the structures are like (44):

18

Liao, Wei-wen

(44)

AspP

vPi

i. habitual state

ii. resultant state

iii. target state

iv. process

[homogenous]

Asp'

RT-Dur.

Asp

Asp'

ti

Therefore, the ungrammaticality in (42 a, b, d) falls into the violation of the homogeneous

requirement.

How do we explain (42c), where the co-occurrence restriction holds between the

TS-related and the P-related durative phrases? I argue that the reason is attributed to a general

linguistic phenomenon. That is, only main predicate can receive aspectual marking and

license the durative phrases. Therefore, the question, to be precise, is how the durative phrase

(of TS-related reading) can be licensed by the secondary predicate.

Higginbotham (1994) may have provided a clue for this question. He claims that the

secondary predicate can sometimes function as the semantic main predicate:

(45) The boat floated [under the bridge].

a. ‘(atelic reading): Under the bridge, the boat floated.’

b. ‘(telic reading): The boat went under the bridge in the manner of floating.’

When under is taken to be telic (meaning ‘go under’) as in (45b), the PP under the bridge

functions as the main predicate:

(46) float (the boat, e1) & under (the bridge, e1, e2) & in an hour (e1, e2)

I suggest that the case in Chinese is similar. That is, the secondary predicate in Chinese can

function as the main predicate when it induces a target state. For example, the secondary

predicate jin shui-li ‘into the water’ in (31) actually functions as a semantic main predicate:

(47) jump (ZS, e1) & into (the water, e1, e2) & for five minutes (e2)

Therefore, not only in the P-related (the typical main predicate), but in the TS-related

interpretations (the semantic main predicate) as well, it is actually the main predicates that

receive the aspectual marking, and are able to license the durative phrases. Therefore, the

P-related and the TS-related may never co-exist with each other because we have only one

main predicate in each sentence. This point again evidences the proposed analysis.

19

Liao, Wei-wen

6

Conclusion

I have shown the structures of the aspect and the durative phrases in Chinese and the

interaction between semantics and syntax of aspect. To summarize, the durative adverbs in

Chinese can have three kinds of interpretations, namely, the TS-related, P-related, and

RT-related readings. The interpretations can be attributed to the aspectual structure which

contains three levels of aspects. The durative phrase of the TS-related reading modifies the

root projection or the resultative predicate, hence the lexico-compositional asepct. The

durative phrase of the P-related reading modifies the viewpoint aspect level (verb-le). The

durative phrase of the RT-related reading modifies the temporal aspect level (sentence-le).

The distinction not only solves the semantic issues of telicity but also characterizes an

elaborated architecture of aspect and the durative adverbs in Chinese.

20

Liao, Wei-wen

REFERNCES

Binnick, Robert I. 1991. Time and Verb: a guide to tense and aspect. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Bowers, John. 1993. The Syntax of Predication. Linguistic Inquiry 24.591-656.

Cheng, Lisa. 1991. On the Typology of Wh-questions. Cambridge, MA: MIT dissertation.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by Phase. Ken Hale: a Life in Language, ed. by Michael

Kenstowicz, 1-52. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chung, Sandra, and Alan Timberlake. 1985. Tense, Aspect, and Mood. Language Typology

and Syntactic Description Vol.III: Grammatical Categories and the Lexicon, ed. by S.

timothy, 202-258. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and Funtional Heads. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ernst, Thomas. 1987. Duration Adverbials and Chinese Phrase Structure. Journal of Chinese

Language Teachers Association 22.1-11.

Hale, Kenneth, and Samuel J. Keyser. 1993. On Argument Structure and the Lexical

Expression of Syntactic Relation. The View from Building 20: Essays in Linguistics in

Honor of Sylvain Bromberger, ed. by Kenneth Hale and Samuel J. Keyser, 51-109.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hale, Kenneth, and Samuel J. Keyser. 1997. On the Complex Nature of Simple Predicators.

Complex Predicates, ed. by Alex Alsina, Joan Bresnan, and Peter Sells 29-66. Stanford,

California: CSLI Publications.

Hale, Kenneth, and Samuel J. Keyser. 2002. Prolegonmenon to a Theory of Argument

Structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Higginbotham, James. 1994. Sense and Syntax. Inaugural lecture, University of Oxford.

Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Hornstein, Norbert. 1990. As Time Goes by. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1982. Logical Relations in Chinese and the Theory of Grammar.

Cambridge, MA: MIT dissertation.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1984.

Kang, Jian. 1999. The Composition of the Perfective Aspect in Mandarin Chinese. Boston,

MA: Boston Univertiry dissertation.

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The Antisymmetry of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

Klein, Wolfgang. 1994. Time in Language. New York: Routledge.

Klein,Wolfgang, Li Ping, and Henriette Hendriks. 2000. Aspect and Assertion in Mandarin

Chinese. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 18.723-70.

Larson, Richard. 1988. On the Double-object Construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19.335-91.

Li, Yen-hui Audrey. 1987. Durational Phrases: distribution and interpretations. Journal of

Chinese Language Teachers Association 22.27-66.

Liao, Wei-wen Roger. 2004. The Architecture of Aspect and Duration. Hsinchu, Taiwan:

National Tsing Hua University MA thesis.

21

Liao, Wei-wen

Lin, Jo-wang. 2000. On the Temporal Meaning of the Verbal –le in Chinese. Language and

Linguisitics 1.109-33.

Lin, Jo-wang. 2003a. Event Decomposition and the Syntax and Semantics of Durative

Phrases in Chinese. Paper presented in the 2nd conference on formal syntax and

semantics. Taipei: Academia Sinica.

Lin, Jo-wang. 2003b. Temporal Reference in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian

Linguistics 12.259-311.

Lin, Tzong-hong Jonah. 2001. Light Verb Syntax and the Theory of Phrase Structure. Irvine,

CA: University of California dissertation.

Lin, Tzong-hong Jonah & Wei-wen Roger Liao. 2003. Eliminating Right Adjunction:

Evidence from the Clauses of Result in Chinese. Paper presented in the 2nd conference

on formal syntax and semantics. Taipei: Academia Sinica.

Liu, Xun-ning. 1988. Xiandai Hanyu Ciwei ‘le’ de Yufa Yiyi. [The grammar of suffix ‘-le’ in

Modern Chinese.] Zhongguo Yuwen 5.321-30.

Moltmann, Friederike. 1991. Measure Adverbials. Linguistics and Philosophy 14: 629-60.

Parsons, Terence. 1990. Events in the Semantics of English: a Study in Subatomic Semantics.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Piñón, Christopher. 1999. Duration Adverbials for Result States. WCCFL 18 Proceedings, ed.

by S. Bird, A. Carnie, J. Haugen, P. Norquest, 420-433. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Reichanbach, Hans. 1947. Elements of Symbolic Logic. Berkeley: University of California

Press.

Shen, Li. 2004. Aspect Agreement and Light Verbs in Chinese: a Comparison with Japenese.

Journal of East Asian Linguistics 13.141-179.

Smith, S. Carlota. 1991. The Parameter of Aspect. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer.

Sybesma, Rint. 1997. Why Chinese –le1 is a resultative predicate. Journal of East Asian

Linaguistics 6.215-261

Sybesma, Rint. 1999. The Mandarin VP. Dordrecht, Netherland: Kluwer.

Tang, Chih-chen Jane. 1990. Chinese Phrase Structure and the Extended X-bar Theory. Ithca,

NY: Cornell University dissertation.

Tenny, Carol. 2000. Core Events and Adverbial Modification. Events as Grammatical Objects,

ed. by Carol Tenny and James Pustejovsky 285-334. Standford, CA: CSLI Publications.

Tsai, Wei-tian Dylan. 1994. On Economizing the Theory of A-bar Dependency. Cambridge,

MA: MIT dissertation.

22