Article Summary for Wiki

advertisement

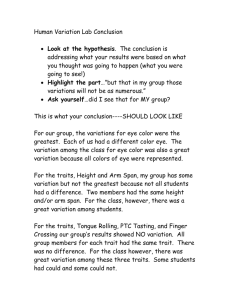

Evolution of Personality 1 Summary of: Nettle, D. (2006). The evolution of personality variation in humans and other animals. American Psychologist, 61 (6) 622-631. Summary by Nikoo Naimi and Sarah Krouse For Dr. Mills' Psyc 452 class, Spring, 2008 Recently in the field of Psychology there has been increasing interest in evolutionary explanations, because it is believed that behavioral and psychological mechanisms that are common must serve a fitness-enhancing function. However, there has been little focus on variations of traits. Some evolutionary psychologists believe that selection will discard variation within traits. This belief is due to the fact that natural selection is supposed to maintain only the “highest fitness variant at a particular locus” (Nettle, 2006, p.622), and all other forms should be weeded out. Furthermore, many evolutionary psychologists reason that a trait that has variation usually does not have adaptive significance. Buss (1991), Buss and Greiling (1999), and Tooby and Cosmides (1992) suggest that possible interindividual variations with functional relevance do exist. MacDonald (1995) implies that trade-offs can exist where individuals within the same normal range of a personality dimension may achieve the same levels of fitness through different means. This indicates that increasing a trait may produce a benefit in fitness and will also produce a cost, hence the word trade-off. In this article, Nettles pays “particular attention to the way that selection can allow variation to persist even when it is relevant to fitness” (Nettle, 2006, p. 623). He also focuses on “Macdonald’s ideas of personality dimensions as alternative viable strategies, outlining a more explicit framework of costs and benefits, and [applies] this framework to each of the dimensions of the five-factor model of personality” (Nettle, 2006, p. 623). He first reviews variations among nonhuman species, then persists to review them within the five-factor model of personality in humans. It is a common understanding that humans vary both in phenotype and in genotype. Many human variations result in variation among behavioral traits and have functional significance. For example, a genetic variation can result in a psychological disorder, such as schizophrenia, which can affect life expectancy and reproductive success. In this case the source of variation is mutation. Therefore, the amount of variation that exists in a population at a certain time is a result of the difference between how many variations are introduced by a mutation and how many variations are being subtracted through selection. The greater number of genes that influence a trait, the greater the possibility of variation in that trait, and the lesser the possibility of removing the variation. Most traits have both advantages and disadvantages. For instance in the pygmy swordtail, females prefer larger males. Larger males have greater reproductive advantage, however, larger males also take 27 weeks to develop, as opposed to 14 weeks for the smaller males. Therefore they miss out on many opportunities to copulate. In addition, at a certain time a specific trait may be more desirable than another. For example, in the Galapagos finches, there was a dry year Evolution of Personality 2 which resulted in a shortage of seeds. During this time finches with large deep beaks were at a greater advantage because they were able to break open large hard seeds. This resulted in a greater average body size. In contrast, when the weather was wetter finches with small beaks became more abundant. There is considerable variation in each trait and, depending on the context and situation, each trait may be seen as beneficial or harmful. This may be applied to behavioral dispositions as well. For example, within a species called the great tit, there is a behavioral variation in exploration. When there is limited food females with higher exploration scores have a higher chance of survival. However, when there is an abundance of resources they have a lower survival rate. The opposite of this holds true for males of this species. This is because they live in a male dominated society and the males compete for territory, thus in poor years fewer great tits survive giving the males less incentive to fight for territory. However, in good years males fight harder for territory and consequently have a higher mortality rate. This demonstrates how the condition at a given point in time, as well as the sex of the species, determine whether high or low exploration levels can be either a cost or a benefit. Nettle discusses another theory known as negative frequency-dependent selection. This process occurs when traits have increased fitness when they are rare, but their fitness decreases as they become more common. After discussing many examples in nonhuman species Nettle makes two generalizations: “first, variation is a normal and ubiquitous result of the fluctuating nature of selection, coupled with the large numbers of genes that can affect behavior” and “second, behavioral alternatives can be considered as trade-offs, with a particular trait producing not unalloyed advantage but a mixture of costs and benefits such that the optimal value for fitness may depend on very specific local circumstances” (Nettle, 2006). He then considers costs and benefits in the five specific human traits (see figure.1). Nettle focuses on the five-factor model of personality because “there is broad consensus that they are useful representations of the major axes of variation in human disposition” (Nettle, 2006, p. 625). The first trait is extraversion, which is referred to as “positive emotion, exploratory activity, and reward”(Nettle, 2006, p. 625). A benefit of extraversion is that people who demonstrate more extraversion usually have more sexual partners, which, increases fitness in men. In addition, extroverted individuals are more likely to leave one partner for another, enabling them to secure higher quality mates. In addition, extraverts are more likely to explore their environment. Costs of being an extravert are that they are more likely to expose themselves to risk. This is demonstrated by the fact that they have a higher tendency to land in the hospital or get arrested, which results in threats to their survival and possibly the survival of their offspring. The second trait is neuroticism which is referred to as “negative emotion systems such as fear, sadness, anxiety, and guilt” (Nettle, 2006, 626). The costs come in the form of psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety, as well as other damages to physical health, relationship failure, and social isolation. There are few benefits but some are avoiding dangerous situations, speeding up reaction time to and detecting threatening stimuli, and motivating competitiveness. Evolution of Personality 3 Nettle then discusses openness. A positive aspect of high levels of openness is its positive correlation to creativity, which has been found to attract mates, therefore, leading to mating success. On the negative side, however, openness has also been found to hinder reproductive success when it leads to schizophrenia and beliefs in the paranormal. Another negative point is that openness has been associated with depression. Nettle discusses conscientiousness, which “involves orderliness and self-control in the pursuit of goals” (Nettle, 2006, p. 627). Life expectancy is positively associated with conscientiousness, since conscientiousness is concerned more with life’s long term plan than with immediate gratification. It is also related to healthy behaviors and avoiding unhygienic risks. Conversely, extreme traits of conscientiousness, such as self control and perfectionism, are associated with patients with eating disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder. These extreme behaviors can lead to overlooking spontaneous chances for reproduction. The final trait that Nettle discusses is agreeableness. A benefit of agreeableness is that it is positively correlated with “awareness of others’ mental states” (Nettle, 2006, p. 627). Other benefits include avoiding violence and being cooperative. This makes highly agreeable people attractive as friends and as coalition partners. Conversely, high levels of agreeableness tend to result in too much attention to others’ needs and excessive trusting in others, which could harm fitness. Therefore, although agreeableness may be beneficial in social exchanges it is costly in terms of fitness. Nettle concludes that each trait leads to the maintenance of polymorphism. After reviewing each of the five traits, he explains that there will be great amounts of variation of each trait in different contexts, and that the trait may be seen as a cost or a benefit with respect to how much it is displayed and the context of the environment. In conclusion, Nettle claims that a normal outcome of evolution results in plenty of heritable variation in different populations. He claims that a valuable way of examining this variation is by looking at the trade-offs of different benefits and costs. The notion of trade-offs has been used to explain diversity, because, due to selection, fluctuations in environment lead to variation in phenotypes. Nettle states his agreement with MacDonald’s (1995) discoveries. He claims that there are disadvantages at the extremes of personality traits, and that selection fluctuates and can be directional in order to increase or decrease a trait at any given time. However, Nettle argues that there are not necessarily always stabilizing effects. Nettle comments that trade-offs and fluctuating selection are not the only possible explanations for heritable variation, “there are a number of traits that are unidirectionallly correlated with fitness and yet in which substantial heritable variation is maintained” (Nettle, 2006, p. 628). For example physical symmetry is highly correlated to fitness, however great variation continues to exist. It is suggested that this variation is due to the large amount of genes involved in creating symmetry. However, he maintains the claim that when discussing personality “the combination of trade-offs and genetic polymorphism seems a fruitful avenue to pursue” (Nettle, 2006 pg.629). Evolution of Personality Figure 1 Adapted from Nettle (2006) p. 628 Personality Trait Benefits Have more mates; explore Extraversion their environment 4 Costs Expose self to risk; lack of family stability Avoiding dangerous situations; detecting and quickly reacting to threats; motivating competitiveness Psychiatric disorders (i.e. depression and stress); damages to physical health Openness Creativity, which leads to mating success Leads to paranormal beliefs and psychosis Conscientiousness Longer life expectancy; attention to long term goals; Overlooking spontaneous reproduction possibilities; associated with eating disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder Excessive trusting in others; missing out on opportunities Neuroticism Agreeableness Aware of others’ mental states; avoid violence; cooperative; valued friend and coalition partner Outline of: Nettle, D. (2006). The evolution of personality variation in humans and other animals. American Psychologist, 61 (6) 622-631. Outline by Nikoo Naimi and Sarah Krouse I. Introduction: Review of Previous Research a. Previous research hasn’t paid much attention to variation in traits because they believed, due to natural selection, important traits would not have much variation. b. Tooby and Comsides (1992), Buss (1991), and Buss and Greiling (1999) suggest, however, that there may be some heritable variations that serve a functional purpose. c. It is suggested that variation can come about through trade-offs. Where individuals within the same normal range of a personality dimension may achieve the same levels of fitness through different means. This means that some tradeoff exists where if one component of fitness is increased by increasing a trait another component will suffer. Evolution of Personality 5 II. Purpose of Article a. To review variation between individuals in nonhuman species, especially in functionally relevant traits. b. To review costs and benefits of the five-factor model of personality. III. Variation in Humans a. There is evidence of interindividual variation in humans on both the phenotypic and genotypic level, and that it is unlikely that these variations don’t serve a function. IV. Variations in Nonhuman Species a. Discusses variations that exist within a different species and how the optimum value of each trait varies and depends on context. b. Due to environmental changes selection favors different traits at different times, therefore selection creates diversity within a species. c. Example: Within the pygmy swordtail large males are desired but take longer to develop, on the other hand smaller males develop sooner and are able to sneak up on the women and copulate with them. Therefore there is a trade-off of costs and benefits to each variation and different contexts yield different advantages to each variation. V. Costs and Benefits of the Five-Factor Model of Personality in Humans a. Extraversion is engaging in exploration and positive emotion i. Benefits: Have more mates and explore their environment ii. Costs: Expose self to risk and lack of family stability b. Neuroticism is defined as “negative emotion systems such as fear, sadness, anxiety, and guilt” i. Benefits: Avoiding dangerous situations; detecting and quickly reacting to threats; motivating competitiveness ii. Costs: Psychiatric disorders (i.e. depression and stress) and damages to physical health c. Openness i. Benefits: Creativity, which leads to mating success ii. Costs: Leads to paranormal beliefs and psychosis d. Conscientiousness defined as exhibiting self-control and orderliness when pursuing goals i. Benefits: Longer life expectancy and attention to long term goals ii. Costs: Overlooking spontaneous reproduction possibilities and associated with eating disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder e. Agreeableness i. Benefits: Aware of others’ mental states, avoid violence, cooperative, and a valued friend and coalition partner ii. Costs: Excessive trusting in others and missing out on opportunities VI. Conclusion Evolution of Personality 6 a. There is considerable variation in each trait and depending on the context and situation each trait may be seen as beneficial or harmful. b. Evolution results in considerable variation within animal and human populations. The notion of trade-offs has been used to explain diversity, because, due to selection, fluctuations in environment lead to variation in phenotypes. Test Questions MULTIPLE CHOICE 1. Nettle identifies beneficial qualities of agreeableness. Which one does he NOT include? A. avoiding violence B. being cooperative C. satisfaction with mate D. having the ability to track the mental states of others 2. The notion of trade-offs has been used to explain which of the following themes: A. differential selection B. diversity C. sexual selection D. random noise 3. Nettle identifies neuroticism as having more costs than benefits. Which of the following is NOT a cost he identifies? A. depression B. anxiety C. damages to physical health D. None of the above (All of the above are costs) TRUE/FALSE 4. Humans vary in phenotype, but not genotype. 5. Physical symmetry is highly correlated to fitness. 6. The greater number of genes which influence a trait leads to a lesser possibility of variation in that trait. ANSWER KEY 1. C: satisfaction with mate 2. B: diversity 3. D: none of the above 4. False 5. True 6. False