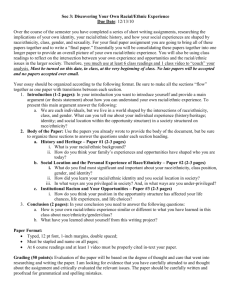

iversity and Higher Education: Theory and Impact on Educational

advertisement