MERGING SEMI-LEXICAL HEADS

advertisement

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 4

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

LATE MERGE OF FREE MORPHEMES BY AR

University of Newcastle, Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

I. The best candidate for “a Principle of Morphology”

Throughout these lectures, I work with a distinction between the X1 structures of phrasal/

sentential syntax and the X0 structures of possibly complex words as in (1):

(1)

a. a [A work induced anxiety free] environment

b. that new [N non-spatial perception assessment training course materials centre]

c. A complex V with many bound morphemes (French):

[V Elle - s ne se re - dé - magnét - ise - r - ont] pas.

[ she-PL-NEG-REFL-re-NEG-magnet-CAUSE-FUT-PL ] NEG

‘They won’t redemagnetize.’

Exercise: Assume that all the morphemes in the above large X0 are themselves types of Y0,

consistent with the “No Phrase Constraint” (19) of Topic 1. Draw the 3 word-internal trees!

The structure of such combinations inside X0 is independent of lexical listing because they

result from productive syntactic processes. Syntactic theory must explain structure inside X0.

Domains of Morphology. We saw in Topic 2 that language-particular subsets of word

domains may result in the suppression of certain syntactic information in PF:

English Morphology: If a daughter X0 of a Y0 has only syntactic head features Fi,

then Y0 exits the syntax into PF with no X0 label. (Not valid for French)

(2)

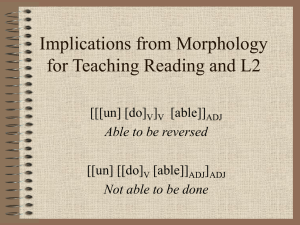

These lectures are examining the question: Are language particular domains of “Morphology”

defined by statements like (2) subject to some additional rule(s) or principle(s) limited to

these domains? If so, it would make sense to speak of a “Morphological Component” (MS).

My investigations support a categorical no. However, one plausible candidate (4) could be

the generalization of the Merger operation of Halle and Marantz (1993) introduced in Topic

3.

(3)

Canonical Position. A position in LF where a feature F is interpreted is called a

canonical position. These positions are specified in Universal Grammar.

(4)

Merger/ Alternative Realization (“AR”). A syntactic feature F whose canonical

position in LF is on a category β can also be realized by a closed class morpheme

under γ0, provided projections of β and γ are sisters.

AR on bound morphemes expresses the local relation between inflections expressing

features F and the canonical positions of these F. Many bound morphemes (e.g. in astronaut, e-market, micro-manage, neo-phile, rumor-monger, worry-free, etc.) don’t involve AR.

1

Thus PAST, a canonical feature of I, can be alternatively realized under V or C.

When canonical P features of PPs are spelled out under higher Vs, the Vs are called

applicatives. When realized in lower DPs, they are called “semantic case” features.

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 4

(5)

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

Another example: SOURCE is a canonical feature of [P, DIR]; it can be alternatively

realized lower in D (French du) or higher as a V-affix. E.g. the English prefix de-:

de-stress the ending = take stress away from the ending

de-regulate trade = take regulating away from trade

decode messages = take code away from messages

Topic 3 argued that all of what traditional grammar calls inflection is basically Merger/AR

exemplified by bound morphemes. If AR does nothing else, it is a principle of Morphology.

The question that arises in this course is thus: is the most general form of Merger, which I

call AR, a specifically morphological principle (used only for bound morphemes)? If not,

this apparent principle should be “distributed” to another component. In this case the obvious

candidate is syntax, since all terms used in defining AR (4) are syntactic.

Even if AR is more general than morphology, its function should remain the same. Now its

principle function of is to replace overt morphemes with empty categories, presumably for

reasons of Economy. When AR occurs only with such empty categories, it is “unmarked.”

(6)

Invisible Category Principle. In lexically unmarked uses of AR, [β, F] must be null

if all of β’s features except β itself are alternatively realized (from Emonds, 1987).

This function of AR (to increase the Economy of PF representations) suggests that any wider

use in syntax should also yield derivations with fewer words (= free morphemes), with

canonical positions either (a) always or (b) whenever possible empty in the presence of AR.

AR realizes features in positions where they are not interpreted (3). Therefore, if all a

morpheme’s features are alternative realizations, then it should not bet accessible to LF, i.e.

AR must be realized only in PF. In other words, AR is simply Merge in PF.

II. Alternative Realizations of P and I features on N/ D free morphemes

(i) Bare NP adverbials. The effects of AR are not limited to features on bound morphemes

(Emonds 2000: Ch 4). Consider for example contrasts in (7) based on Larson (1987): the

verbs act and behave allow PPs or APs of manner, and phrase and word require them.

(7)

Nobody acts ({ that same way/ *such rowdy fashion}) at movies anymore.

The children should behave ({ some other way/ *a dignified manner}).

Mary { phrased/ worded } her response { the way I said to/ *a style I didn’t like}.

In English manner PPs the usual P is in. As seen in (7), it can be zero with way, though not

with other nouns of manner. This is plausibly because the grammatical noun way optionally

alternatively realizes a feature of P, plausibly of “abstract location.” 1

If this proposal is right, AR has an effect outside of “morphology” and can affect syntax.

(ii) French articles. Monosyllabic contractions of French definite articles are well-known:

In order to use AR to explain [P Ø ] [DP….way…], DP must be considered as an “extended projection

of N0,” to satisfy the sisterhood required in (4). This extended sisterhood was discussed in Topic 3.

1

2

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 4

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

à + le au; à + les aux; de + le du; de + les des

Rough glosses: à = ‘to’ or ‘at’; de = ‘of’ or ‘from’; le, les = ‘the’ (MASC or PLUR)

The Ps à and de realize basic features of P, namely ±PATH, ±SOURCE. With a following

Masculine or Plural definite article, these features are alternatively realized on D. We know

the contractions are not under P, since du/ des sometimes also occur where no PP is possible.

(8)

(iii) English pronominal case. Unmarked English pronouns are those known as “objective”:

me, us, him, her, them. We say “unmarked” because of their use in predicate nominals, focus

in cleft sentences and dislocations. The “subjective” forms, I, we, he, she, they are marked.

A number of reasons militate against attributing English subjective pronouns to “abstract case

marking,” unlike counterparts in languages with productive morphological case (Emonds

1985: Ch. 5). Rather, since I’ and DP are sisters and so constitute an AR configuration (4):

(9)

English case. Subjective pronouns alternatively realize the category I on D subjects.

(iv) English generic expressions the + Adj. English definite articles obligatorily require Ns:

(10)

The town had both rich and poor streets. We visited the rich *(ones) to impress him.

My boss hated those customers. He especially criticized the two young *(ones).

Among her friends, the tall *(ones) look better in high heels.

However, the + Adj is a well formed DP if its reference is generic, plural and human:

(11)

We visited the poor (people/ *ones) to save our souls.

My boss especially criticizes the young (people/ *ones).

The tall (people/ *ones) look better in high heels.

I conclude that a sub-entry of the alternatively realizes precisely these three features of a head

ones of its sister NP in the context of a following Adj, leading to the zeroing of ones, by (6).

Exercise: Propose and justify some further instance of AR involving only free morphemes.

Conclusion. The distributions of these monomorphemic forms (way, au(x), du, I, he, the

etc.), as determined by their syntactic contexts, are not “Morphology,” unless we replace the

traditional definition of morphology with one that encompasses free morphemes.

So we must conclude that AR (4), which is a generalized form of Halle and Marantz’s

Merger, describes possible feature co-occurrences in grammatical items generally, whether

they are realized as bound or free morphemes. That is, AR applies throughout syntax.

If so, AR cannot be a principle in some autonomous morphological component.

III. Alternative Realizations of V features by free morphemes in I

(i) AUXILIARY do. A famous exemplar of “pure syntax” is Chomsky’s (1957) rule of dosupport. His analysis greatly simplified describing many English syntactic constructions such

as tag questions, sentence negation, emphatic do, inversion in questions and VP ellipsis.

3

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 4

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

The essence of his account is simple: a “late” transformational rule inserts the unmarked verb

do under I, provided that no other free form occurs there. But two points require explanation:

(12) What makes do-insertion to apply “late” in transformational derivations, after syntax?

(13)

Why is do in this usage not restricted to “activity” verbs, unlike e.g. do so, do it, etc?

(14)

You resemble Bill, don’t you (*do so)?

Susan doesn’t own a car. But her friend does (*so).

Though Bill {mimics/ *resembles} me, I wish he wouldn’t do so.

She didn’t { buy/ *own } a car, but she should do it soon.

Re (12): The “late” status of do-insertion (and of Chomsky’s affix movement as well) is

explained if it is simply a lexical insertion in PF, i.e. an instance of AR. In this case, V itself

is the “unmarked syntactic feature” of V alternatively realized under I by do.

Re (13): “ACTIVITY” is simply the LF interpretation of a V in canonical position. The fact

that [V do ] is inserted under I in non-canonical position implies that the category V in doinsertion is unavailable in LF, i.e. AR explains why auxiliary do has no activity interpretation.

There remains a problem of formalizing a lexical entry for do. Since its category is

V, how do we indicate that it can also occur in I (unlike the morphemes get, be, go)?

Exercise: Can you improve on the following scenario? If we assume the first category in a

lexical entry is its syntactic location, this first category for do may be optional I. Then, if I is

not chosen, V is the tree location of do; if I is chosen, V becomes a non-canonical F under I.

(15)

Lexical entry for English do. do, (I, -MODAL), V

(ii) STATIVE be. The English finite copulas (am, are, is, was, were) are known to have the

syntax of an I rather than V; they appear in tag questions, invert in questions, precede n’t, etc.

I claim that the essence of these unique forms is to alternatively realize in I a marked feature

STATIVE of a main grammatical verb unspecified for other features, i.e. of the copula be:

(16)

Entries for English past copulas. I, -MODAL, STATIVE, PAST, were, PLURAL

was

The grammatical lexicon lists only “outputs” of AR, i.e. choices for [I, STATIVE]. No ad hoc

be-raising rule, subject to conditions and restrictions, is needed to account for these forms.

Retaining a be-raising rule would not avoid listing output forms, as they are phonologically

distinct from the putative raised element, namely be. Be-raising is thus indefensible.

The behavior of finite copulas as I rather than V is a cornerstone of English syntax and is

explained by AR. So again, AR has syntactic effects outside morphology strictly construed.

(iii) STATIVE have. The third inflected English verb that can appear in I is have (17). In

some stative uses, e.g. with perfect participles, have must occur in I if it can (18).

(17)

4

Stative have optionally appears in I:

John has a chance, { hasn’t/ doesn’t} he?

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 4

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

Mary { has/ hasn’t/ doesn’t have } so many duties these days.

(18)

Stative have obligatorily appears in I:

The girls { have/ haven’t/ *doesn’t have } eaten yet, {have/ *do} they?

Mary had better finish that task soon, { hadn’t/ *didn’t } she?

The AR framework is strongly confirmed by uses of have as an activity verb. Such

interpretations force have to appear in canonical V position, and not in I:

(19)

Non-stative have excluded under I:

She had a good look at the exhibition, { didn’t/*hadn’t } she?

When on vacation, Tom { has/ doesn’t have/ *hasn’t } a neighbor stay in his house.

What thus unifies have and finite copulas in I is that they all alternatively realize STATIVE.

This shared behavior is not unexpected. A number of authors, including Benveniste (1966),

argue independently that the unmarked stative Vs be and have are in complementary

distribution. That is, be and have are simply different spellings of the same grammatical unit.

Exercise. What exact conditions determine the alternation between be and have?

Here is a try. Have appears only when some following [+N] projection (NP, DP or AP) doesn’t agree

with a subject. This is overt in French: its perfect participles (in the passé composé) don’t agree with

a subject, hence the use of avoir. Nor do certain idiomatic APs:

(20)

Elles avaient très{ chaud/ *chaudes }.

Elle avait { beau/ *belle } parler à son mari.

‘They (FEM, PLUR) were very warm.’

‘She spoke to her husband in vain.’

A wider generalization is: APs in many idiomatic VPs don’t exhibit agreement in French, as seen in

(21), whether we call them “adjectives” or “adverbs.” (Thanks to Mary Fender for many examples.)

(21)

Elle pèse { lourd/ *lourde }.

Elle { risque/ perd } { gros/ *grosse }.

Elle sent { bon/ *bonne }.

Elle mange { léger/ *légère }.

‘She weighs heavy.’

‘She { risks/ loses } heavy.’

‘She smells good.’

‘She eats light.’

When the V in an idiom is a copula (20), a non-agreeing +N phrase forces the choice of avoir ‘have’.

We can look at the presence of “auxiliary Vs” in I from a different angle. Why are the only

two transitive English V that appear under I the unmarked grammatical verbs do and have?

Precisely because: their presence in I perfectly satisfies PF-inserted AR (4).

That is, open class items with semantic features f occur only in N, V, A and P positions,

never in positions like D or I. (See Topic 1, the end of section I.) Without this theoretical

restriction, English auxiliaries could as well be possess and exist.

Auxiliary V in I thus furnish more examples where AR accounts for the distribution of free

morphemes (in syntax). Hence again, AR is not limited to statements for bound morphemes.

IV. Alternative Realizations of C features in SPEC(CP)

5

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 4

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

According to Choshy and Lasnik’s (1977) “Doubly-Filled COMP filter” of Modern English,

if WH forms are present in SPEC(CP), then [C,WH] must be phonetically null rather than if.

These WH forms are either single morphemes (where, when, why, who, whether) or they are

heads of fronted DPs or APs in SPEC(CP): which (big chairs), what (others), how (long).

WH is a feature of the head of the WH-fronted constituents in SPEC(CP). These sisters of C’

thus spell out the only canonical syntactic feature of C.

Exercise: To convince yourself that the doubly-filled COMP filter is just a special case of

AR and the ICP, which categories are F, β and γ in (4) and (6)?

Here AR explains a paradigm and an earlier account of it that is an archetypical instance of

syntax. So once again, AR is not limited to bound morphology.

AR (4) doesn’t require c-command between two constituents β and γ, but only that their

projections be sisters. This is further shown by an English construction in which the suffix ever alternatively realizes the conditional COMP if under a head D inside SPEC(CP).

I assume that all cases of if are [C,WH] and that an additional feature F’ characterizes if in

conditionals (German ob ‘whether’ vs. wenn). The sisters that satisfy (4) are then DP and C’.

(22) [C, WH, F’ If ] you took any Beatle to any city at any time, he’d be mobbed.

[SPEC(CP) Whatever Beatle] [C, WH ,F’ Ø ] you took to any city at any time, he’d be mobbed.

[SPEC(CP) Whatever city] [C, WH, F’ Ø ] you took any Beatle to at any time, he’d be mobbed.

[SPEC(CP) Whenever] [C, WH, F’ Ø ] you took any Beatle to any city, he’d be mobbed.

(23)

CP

C’

SPEC(CP), DP

[D,WH what – [F’ ever ] ]

(NP)

Beatle

[C, WH, F’]

Ø

IP

you took to any city …

Consequently, the head D of the DP in SPEC(CP) here alternatively realizes two features;

one is WH and the other is the F’ of the bound morpheme for German wenn, the suffix –ever.

V. Appropriateness of PF Insertion for Alternative Realization

Morphemes spelling out features in canonical LF positions are inserted before derivations

enter LF, while those whose only features are alternative realizations are inserted in PF.

All instances of AR inflections considered prior to the discussions of section II-IV were PFinserted, because these bound morphemes are not in canonical positions.

However, any morphemes that spell out both a canonical and an alternatively realized feature

are inserted late in a derivation, but before Spell Out. An example is English way.

6

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 4

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

But most instances of AR, such as bound inflectional morphemes, the English auxiliaries do,

was and have, and certain realizations of WH in CPs, involve no canonical features. This

supports the appropriateness of using AR in PF to Merge both free and bound morphemes.

It doesn’t seem appropriate to use the term Merger for AR material treated in this Topic, since

Halle and Marantz apparently intend it as part of their special component (in my view entirely

unneeded) of Morphological Structure. This is then the “difference” between Merger and AR;

there is no reason not to extend Merger (or Late Merge) to syntax, but they do not do this.

VI. Relation of AR to Morphology, Particular Grammars and Head Movement

Traditional Counterparts to AR. English Morphology (2), as well as any correspondingly

defined subset of some language’s well-formed words, are now clearly seen as much smaller

than the range of constructions covered by Alternative Realization (4).

Though one might still maintain that Morphology is a kind of pre-theoretical version of AR,

AR corresponds more closely to what are traditionally called “language-particular grammars.”

Most of what this Topic and the last have treated are exactly in this area. That is, most of

“particular grammar” consists precisely of how a language uses AR to increase its Economy.

Summary. Table (24) matches examples of syntactic features of categories in canonical

positions (columns one and two) with, typical alternative realizations (column three):

(24)

Syntactic features F

Canonical positions B

Typical AR on X0 =

Tense and modal features

I

V (lower); C (higher)

STATIVE vs. ACTIVITY

V

I (higher); D (lower)

PERFECTIVE (aspect)

V

I; direct object D

D or NUM

D (higher); N (lower)

LOCATION and PATH features

P

V (higher); D (lower)

ANIMATE, COUNT vs. MASS

N

D and NUM

+INHERENT

A

V (Spanish ser vs. estar)

SPEC(DP) or D

V (Romance clitics)

Quantifier or number features

+DEFINITE; +SPECIFIC

Comparing AR to Head Movement. It is tempting to try to conflate these two syntactic

concepts, or rather they are conflated in Baker’s (1988) influential and insightful work.

Upon reflection, however, the two mechanisms are quite different, especially when head to

head movement is properly constrained. True head movement can only be inside single

extended projections (e.g. V to I; N to D) or in a root clause (I to C; Germanic V-second).

These points are extensively argued for in Emonds (2004).

I therefore do not hesitate to let AR and Head Movement co-exist in syntactic theory. They

don’t overlap because of the first property in (25).

7

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 4

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

(25) Properties of Alternative Realization

Properties of Head Movement(s)

affects only some least marked

affects all a category’s members such as

members of a category.

I, V or N.

Lexical entries specify PF positions

are always substitutions (V to I; I to C; N

under an X0, such as prefix, suffix,

to D). Later suffixation and prefixation to

fusion, fission, local dislocation.

moved stems allowed by PF-inserted AR.

Features are positioned lower or

always involves raising within a single

higher than their canonical position.

(properly defined) “extended projection.”

is never sensitive to a root vs.

Grammatical theory determines whether

embedded dichotomy.

the domain is root clauses only.

is defined only for closed class items.

can apply to open classes, such as French

V-raising or Hebrew N to D movement.

Moreover, having two syntactic principles is in any case more parsimonious than postulating

two separate components. I thus deny that there is any special MS level or component.

References for Topics 4

Baker, Mark. 1988. Incorporation: A Theory of Grammatical Function Changing, University

of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Benveniste, Emile. 1966. Problèmes de Linguistique Générale, Gallimard, Paris.

Chomsky, Noam. 1957. Syntactic Structures, Mouton, The Hague.

Chomsky, Noam and Howard Lasnik. 1977. “Filters and Control.” Linguistic Inquiry 425504.

Emonds, Joseph. 1985. A Unified Theory of Syntactic Categories. Foris, Dordrecht.

Emonds, Joseph. 1987. “The Invisible Category Principle.” Linguistic Analysis 18, 613-631.

Emonds, Joseph. 2000. Lexicon and Grammar: the English Syntacticon. Mouton de Gruyter,

Berlin.

Emonds, Joseph. 2004. “Unspecified Categories as the Key to Root Constructions,” in D.

Adger, C. de Cat and G. Tsoulas, eds., Peripheries: Syntactic Edges and their Effects,

75-120. Kluwer, Dordrecht.

Halle, Morris and Alec Marantz. 1993. “Distributed Morphology and the Pieces of

Inflection,” in K. Hale and S. J. Keyser, eds., The View from Building 20: Essays in

Linguistics in Honor of Sylvain Bromberger, MIT Press, Cambridge, 111-176.

Hoeksema, Jack. 1988. “Head-types in Morpho-syntax,” Yearbook of Morphology, G. Booij

and J. van Marle, eds. Foris Publications, Dordrecht, 123-137.

Larson, Richard. 1987. “Bare NP Adverbials.” Linguistic Analysis 18, 595-621.

8