CONSEQUENCE-BASED ARGUMENTS 1 Running head: THE

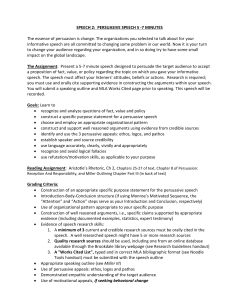

advertisement