Change Management - Dragontooth Training & Consultancy

advertisement

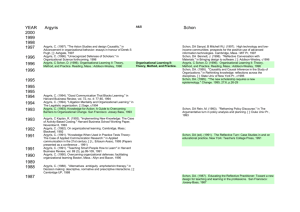

The challenge of change – dealing with change management What is change management? How do I initiate and followed a structured strategy? What are the casual factors in success or failure? How do we ensure a lasting sustainable change? This paper examines ideas surrounding the nature of change management. From the notion that change is ordered and followed blindly from below, to concepts that recognise the need for all staff level involvement and ownership. The need for constant change is ever-present. Pressures such as, greater consumer power, the break down of geographical barriers, political policy and the need to achieve ‘first mover advantages’ means managers and organisations can find themselves in a catch 22. Change needs to be timely and efficient, but staff ownership, commitment and understanding needs securing if change strategies are to be more than superficial and bring about long-term strategic benefit. Change Management – Process or people To understand change management, you need to appreciate its origins – engineering business performance and psychological human approaches. Frederick Taylor (1856-1915) was an American industrial engineer, who whilst working at the Midvale Steel Company studied industrial productivity. This led to the production of detailed systems to gain optimum staff and machine productivity. In 1911 his management methods were published in The Principles of Scientific Management. This led to his nickname ‘The Father of Scientific Management’, and to him being one of the founders of the Efficiency Movement. He was however, of the opinion that workers were incapable of understanding what they were doing, and so change and efficiency had to be managerially enforced. This mechanical ‘clock like’ organisational view can be seen in continual development processes such as TQM (Total Quality Management) and more radical BPR (Business Process Reengineering) as described by Michael Hammer. It focuses on observable, measurable elements that can be improved or changed. Companies using this approach often lack a robust change framework, and aim to isolate any ‘people problems’. 1 On the other side of the coin sits the psychological perspective, and it is William Bridges who is often credited as one of the founders of this ‘people approach’. In 1980 he wrote Transitions: Making Sense of Life's Changes. This was picked up by organisations entering the first round of mergers, reorganisations, and strategic shifts that dominated the last quarter century, and were aware of the need to train managers in change transition, moral and productivity. Bridges recognised a 3-stage ‘re-birth’ of; ending, neutrality and beginning, which is mirrored in Kurt Lewins process of unfreezing (mindset dismantling), change (confusion & transition) and refreezing (crystallising & returning to comfort). Other three stage models include Hughes (1991); exit (departing from an existing state), transit (crossing unknown territory), and entry (attaining a new equilibrium) & Tannenbaum & Hanna (1985) where movement is from homeostasis and holding on, through dying and letting go to rebirth and moving on. Whichever model is chosen it is clear that a successful change management will folow a convergence of both the mechanical and psychological paths, an extreme of either will be unsuccessful. Engineering Mechanical change focus - Process, systems structures (BPR / TQM ). Starts with business issues / opportunities Psychological Human change focus – people, HR. Starts with personal change & actual / potential resistance Convergence = New paradigm of change management An engineering approach will measure financial and statistical ‘hard’ business data, whereas a people approach will observe job satisfaction, employee turnover and productivity loss. What skills do you need? 2 We have already stated the need to walk a line between engineering and people approaches, but what in practical terms does this mean for you as a manager? There are 7 initial questions that any change initiative should start with; Time Frame Nature of expertise Willingness to compromise Degree of resistance Degree of change Numbers involved Stakes (perceived or real) These questions will then determine your overall approach; Directive Expert Negotiating Educative Participative Using an iterative 6-step model and ‘change kaleidoscope’ navigation of a change process is achieved in a systematic controlled manner. This ensures context judgements and design choice decisions are considered in there entirety free from ‘halo and horns’ influences Personal challenges Do you know how to recognise the need for change? Can you locate within your organisation the most suitable ‘change agents’ Do you have a culture of knowledge sharing, negotiation, education and reflective learning? Can you recognise the skills, resources and capabilities that you will require? Can you place your change process in both an internal organisational context and in a wider external environmental arena? Finding out more 3 Argyris, C. and Schön, D. (1974) Theory in practice: Increasing professional effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Argyris, C. and Schön, D. A. (1978) Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Argyris, C. and Schön, D. (1996) Organizational learning II: Theory, method and practice. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley. Bridges. William (1980), Transitions: Making Sense of Life's Changes Hammer, Michael and Champy, James (1993), Reengineering Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution, Harper Business the Lewin K. (1943). Defining the "Field at a Given Time." Psychological Review. 50: 292310. Republished in Resolving Social Conflicts & Field Theory in Social Science, Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 1997 Taylor, Frederick, Scientific Management (includes "Shop Management" (1903), "The Principles of Scientific Management" (1911) and "Testimony Before the Special House Committee" (1912), Routledge, 2003 4